All Content

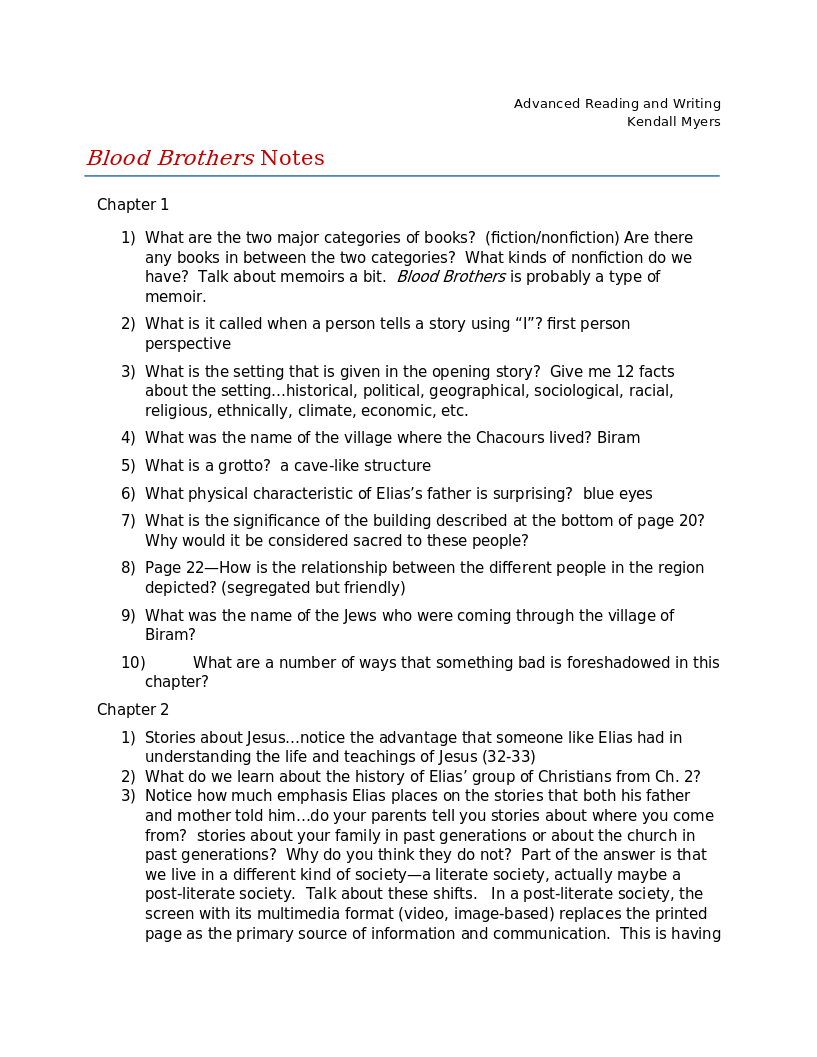

Diagramming Sentences: Strategies for Learning Sentence Structure

These are just a few teaching tips that I've picked up over the years, a lot of them from other teachers.

Cards that leave out nobody

One of my favorites is to put all the students’ names, on these names, on these little cards, and that way nobody gets left out. I scramble them up, and I go through the first one, and I'll set it down or else I'll put it at the back here with my other finger.

And then once I've gone through all of them, and they all have to answer, and if a student doesn't answer—they don't answer correctly—I'll just stick it back in there. And that gives them another chance to answer correctly.

And then when I'm done—and I do this so they know that I'm doing it, and they watch me do it—I tell them, "OK, we're going to shuffle the cards again," and I shuffle them all up so they know that I'm going to call on them to read or answer a question. And they know they might be the next one because they can never figure out the order. So this is one of my very favorite things to do because it causes every student in the room to be focused, to be paying attention, and to know I might be next.

Lessening sentence diagramming confusion

Whenever we're diagraming—again, I use my cards and I will call on them and they can mark—they can tell me whatever they see up here.

For instance, one of them might say, "I see a preposition."

Deana: “OK.”Student: "with."Deana: “So what's the prepositional phrase?”Student: “Well, I'm not sure.”Deana: “What's the next one? What do you see?”Student: “Well, I see subject and verb.”Deana: “OK, what is it?”Student: "I agree."We mark it. I agree.

Deana: “And then what is this? What do you see?”And I'll call in the next person.

Student: "Well, I see another subject and a verb."Deana: “What is it?”Student: "You decide."Deana: “Good.”You decide—subject and a verb.Deana: “So if I have a subject and a verb here, and the subject and the verb here, this must be a clause. Do you see what we call a deer antler or a subordinating conjunction or a relative pronoun, whatever it is.”And they'll say, "whatever," and I'll say "yes." So we mark that.

And again, I like to mark mine. The guys love this. We put deer antlers on it. We'll make him a ten point or whatever that is. A twelve point.

And so we'll say, "Ah ha! This is a clause." And the next student will mark it, and then we go to diagram it.

And we've already done all the hard work. We don't have to see that and then go back and forth and mark it and get all confused. This really helps, especially some of the guys that seem to want to crisscross everything and get all confused.

So we'll mark it.

I agree.And then we'll say, "Now this is a prep phrase, so where does it go?" You agree with whatever you said. So then we'll put it there. And again, nothing crisscrosses.

This is the subject. This is the verb. This prep phrase modifies the verb. Here's our little pedestal because it's a noun clause.

And you. And they'll get tripped up here.So we'll say, "subject and verb."

Deana: "You decide what"?Student: “You decide, whatever."Deana: “Does whatever get decided?”So we'll mark that even as the D.O. There. And that way everything is neatly marked. They just have to bring it down—and it makes it much less confusing—rather than trying to look at it and write it down here. Just take—I always tell them it takes, what, five seconds or something. Just mark it up there.

All the hard work is done. There you go.

Getting Our Students Outside Every Day, Part 3

Interaction with Nature Helps Develop Students Who Care About Nature

While many people in a developed and industrialized country often believe that nature and its resources are mainly there for humans to master and extract from, we should be counteracting this mentality as Christians. Rather, because we believe that God has entrusted us to be His stewards, we have a responsibility to care for His creation. By creating positive experiences within nature for our children, we can influence the next generation to continue caring for His creation.

Within our American natural parks, it is common to see “Leave No Trace” signs which encourage you to both leave no footprint on the environment and not to take anything from the environments such as a shell, driftwood, or pine cone. However, Thomas Thomas Beery, an assistant professor in environmental science at Kristianstad University, Switzerland, found that collecting natural objects can foster play and creativity as well as knowledge of the outdoors. In another study, he showed that college students who had collected items like rocks, shells, insects or foraged foods when they were younger, thought of themselves as more connected to nature than the students who did not collect (p.143). Another study went on to research the natural environments themselves and it was found that environments where there had been some wear and tear actually had better growth and foliage than environments where there had been no trace of human contact and interaction. Using this research, we can draw the conclusion that is both beneficial to humans and to nature to interact with God’s creation.

Practical Ideas to Increase Outdoor Activity for the Children Under Your Care

Let’s get practical. What are some ways that we can get our students out to the greatest classroom on earth, the earth itself? Nature makes subjects like math and physics come alive in a way that simply are not possible inside the classroom such as comparing stick lengths, using the sledding hill to learn about friction (sliding with a wax cloth, plastic shed, or on shoes with grooves), or building canals after a large rainstorm (p. 80).

Every classroom has treats and celebrations that students work towards. Can you take those celebrations and treats outdoors? During the winter, use a sledding hill as a reward system and build an open fire to warm up around with hot dogs to grill. An ice-skating party at a local pond is sure to be a good motivator as well. During the fall, have a leaf raking party and jump in those leaves together. During the spring, allow your students to read outside as much as possible. And throughout the entire year, go on nature hikes to record and observe the changes within the seasons. “Nature looks and acts differently depending on the season and the weather, and in order to understand the changes, you need to experience them firsthand” (p. 192).

Finally, provide time for unstructured play and child-led activities. According to McGurk, “Another advantage of having fewer structured and more child-led activities is that it can improve children’s executive functioning. Essentially, this makes them better able to delay gratification, show self-control, and reach their own life goals” (p.123). If possible, reserve a spot in your school yard where children are allowed to dig in the dirt and create a simple mud kitchen with old pots, pans, cups and other kitchen utensils. As a teacher commented to McGurk, “The outdoors is a free space where children can take risks—it’s how children learn, a form of trial and error. Sometimes it is better for the adult to step back, observe, and not intervene.”

Finally, provide time for unstructured play and child-led activities. According to McGurk, “Another advantage of having fewer structured and more child-led activities is that it can improve children’s executive functioning. Essentially, this makes them better able to delay gratification, show self-control, and reach their own life goals” (p.123). If possible, reserve a spot in your school yard where children are allowed to dig in the dirt and create a simple mud kitchen with old pots, pans, cups and other kitchen utensils. As a teacher commented to McGurk, “The outdoors is a free space where children can take risks—it’s how children learn, a form of trial and error. Sometimes it is better for the adult to step back, observe, and not intervene.”A Call to Reflect and Evaluate

Americans were not always so concerned about the “dangers” of the outdoors. If your parents are anything like mine, they can tell you how they had to walk to school for two miles up hill in every type of weather. Coming back home during the winter, they would sit on their lunch pails and slip and slide down the macadam. According to studies done by McGurk, 70% of American mothers played freely outside while they were young, but now only 29% of their children do so. Instead, the majority of children are spending significant amounts of time getting transported to organized activities and sports instead of having unstructured outdoor play (p.215).

Within our Anabaptist schools, are we slowly following the trends of the world around us and keeping our children inside more than they were a hundred years ago? And if so, is it the trend we want to continue? If not, let’s find ways to encourage each other to get our children into the great outdoors more than we did yesterday.

Sources:MCGURK, L. K. (2018). THERE'S NO SUCH THING AS BAD WEATHER: A Scandinavian mom's secrets for raising healthy, ... resilient, and confident kids. SIMON & SCHUSTER.

Getting Our Students Outside Every Day: Part 2

Outdoor Play and Childhood Health

We all know that physical exercise is beneficial for children, but many of us see indoor exercise as being equivalent in benefits to outdoor exercise. And this is where we are wrong according to studies done by a research team in Sweden. After comparing children at nine different preschools, they found that the more varied and versatile the outdoor environment is, the longer children will stay outside and the more active they will be. According to their research, the places with plenty of trees, shrubs, rocks, and hills also had children with normal body mass instead of the children being overweight. (122) A 2011 study of children in Missouri showed that both genders take more steps and work up higher heart rates when recess is held outside instead of in a gym or classroom. (84-85) In the past, most of our private Mennonite schools did not have the resources or finances to build a gym for the children. However, as of late, more and more schools are choosing to build gyms for their students to spend their recess of time of physical education. When looking at children’s play from a health perspective, we do not seem to be doing our children a favor by having them spend the majority of their active hours indoors instead of outdoors.

Further, a study by the University of Copenhagen showed that the children who played freely outdoors got more exercise than when they participated in organized sports. (122) In contrast to these studies, we have seen childhood obesity continue to rise in America. Instead of only attacking the processed foods and unhealthy diets, can we simply encourage our children to spend more time playing outdoors? Studies have shown that children who are active in school are more likely to stay active after school as well; and of course, the reverse is also true.

Today, about one in ten children within the US suffers from asthma and as many as forty percent have been diagnosed with allergies. In contrast, asthma and allergy remain very rare conditions in many poorer, less-developed countries. Many researchers believe that smaller family sizes, increased antibiotics use, less contact with animals, more time spent indoors, and an obsession with cleanliness have all contributed to our immune systems slacking off in the past fifty years. Many parents (and certainly it is more true today due to COVID-19 than any other time) believe that bacteria and germs are found on playground equipment in parks. And certainly, it is true but are these germs and bacteria so dangerous? Sometimes, we perceive that all germs are bad and should be eliminated at any cost with a bucket of bleach or at the very least, hand sanitizer. Yet, in reality, it seems that our modern, sanitized lifestyle has wiped out a lot of beneficial microbes in our gut that actually help us stay healthy. When we are exposed to certain microbes in the womb and early childhood, that exposure can actually the immune system and protect from illnesses later on. It is when the immune system is not challenged enough, that it might start looking for stuff to do, like overacting to things that are not really dangerous such as pollen and peanuts. (p.181)

While scientists do not know exactly what type of dirt can help protect us but some speculate that by simply being more removed from nature has become the main reason for the epidemic. Perhaps an easier way to support children’s health could be by allowing them to play outside as much as possible and not panic when they eat dirt or lick an earthworm. (185) Scientists have found that the mycobacterium vaccae (a type of bacteria that is found in dirt) is beneficial to health. In a research study, it was found that Amish children as well as children who live in poorer and dirtier conditions had a greater exposure to it than children in most developed countries. (182-184) Another study was done on mice showing that mice that were exposed to the M. vaccae did better than those who weren’t. Scientists believe that the M. vaccae may decrease anxiety and improve the ability to learn new tasks. (183) In fact, according to The Dirt Cure: Growing Healthy Kids with Food Straight from the Soil, “Bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi play a critical role in developing and maintaining a healthy gut and immune system. Playing outside, digging for worms, planting vegetables, and essentially coming into contact with plenty of dirt and livestock are actually good things. Not just good – essential.” (184)

McGurk’s research shows there are many other health benefits of outdoor recess. The fresh air helps to oxygenate the cells with fresh air which in turn makes one feel more energetic and alive. Also, several studies have shown that outdoor recess can help prevent nearsightedness because children’s eyes need bright, natural light to develop appropriately. An educator confided to McGurk, “We’ve never had to explain to a parent why the kids are outside. Everybody understands that it’s good for them – the fresh air, the big space. There are fewer conflicts and infections, because the kids are not on top of each other all the time. We may have had a couple cases of stomach flu but we don’t get the epidemics that other places have. There’s also less noise. We see a lot of advantages of being outside.” (84)

Outdoor Play and Childhood Development

Outdoor Play and Childhood Development

In addition to health benefits, outdoor play has also shown to greatly benefit childhood development. In a study done by a kindergarten teacher comparing the differences between richly stimulating outdoor environments, found that “those who played in a forest daily had significantly better balance and coordination than children who only played on a traditional playground. Once again, the reason is believed to be that children are faced with more complex physical challenges in nature, and that this boosts their motor skills and overall fitness.” Again, not all exercise seems to be created equal and not even all outdoor activities seem to be of equal importance. She went on to say that children who spend a lot of time in nature have stronger hands, arms, and legs and significantly better balance than children who rarely get to move freely in natural areas. In nature children use and exercise their joints and muscles, if only given the opportunity.” (123)

Outdoor play is also the ultimate sensory experience. Barefoot running, sinking into mud, listening to birds, and feeling raindrops are all part of stimulating sensory integration. In a country like America where autism and ADHD is on the steady rise in contrast to children in Norway who are spending more time outdoors (89), any research pertaining good sensory integration is important. Sensory integration relates to the body’s ability to process and organize information that is received through the senses. There are certain parts of the brain that are stimulated when interacting in a varied environment. (141-142)

Stay tuned for Part 3 which will reflect on how we should be approaching nature as Christians. The post will also give you several practical ideas on ways you can make use of the great outdoors with your students.Sources:MCGURK, L. K. (2018). THERE'S NO SUCH THING AS BAD WEATHER: A Scandinavian mom's secrets for raising healthy, ... resilient, and confident kids. SIMON & SCHUSTER.

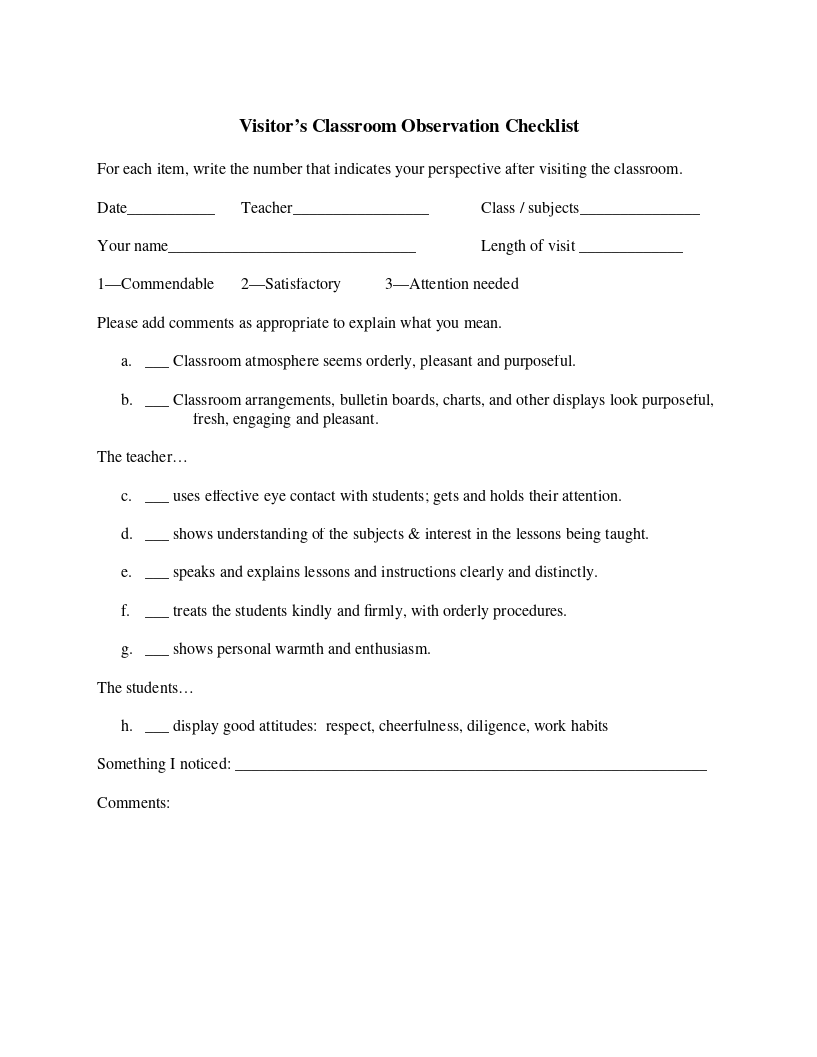

Classroom Management: Practical Advice for Large Classrooms

I teach in a very large class. There's twenty students, and we typically have somewhere between fifteen to twenty-three students in our classes. So that requires some classroom management in a way that you may not need if you are doing a smaller class. So I thought I would focus in on some things that you definitely need for a larger class. It may apply to a smaller class, but it's absolutely needed for a larger class.

Expectations

First of all, it's really important at the beginning of the year in any classroom to be very clear about your expectations and to have some procedures set ahead of time that you practice that the students know exactly what's expected.

Distributing Papers

One thing, for example, is to practice handing papers in and out that they know exactly what's expected. You can waste a lot of time with twenty students if they're not sure what to do or if it happens different ways every time. So I practice handing the papers out. I actually have them passed across rather than back in front so that they are ready to—they can see their neighbor ready to hand the paper to them. That requires me to walk down the side of the classroom, but it works a lot better than them handing papers over their heads. The papers always go the same direction. I hand them out on one side of the room. They're always passed across that direction and when they hand them in, they end up on the opposite side, so that papers always go the same direction. The student in the front of the classroom and in the back of the classroom on that side are taught and prepared to stand up and collect the papers and either take them to the back of the room or bring them to me in the front according to what it is. And they know in a moment what to do.

We practice that on the first day of school and a little bit in the first weeks, and then for the rest of the year it can happen very smoothly. They sometimes need a reminder, but that's very helpful in getting papers passed in and out and usually only a simple reminder later we'll brush that up.

Maintaining Silence

I think it's especially important with a large classroom to maintain a moderately quiet classroom. Every school kind of has its own culture of what is OK and what's not. But if you allow a large class to be very noisy, it will get out of control very quickly because there are so many of them, so I think you need to be very clear about those expectations. If that means there is no talking between, whether it's classes or between activities, then enforce that. Or if you have a small amount of talk aloud, then teach them how to end that at a certain time and end it very quickly, and practice that so they know that it's time for the next thing. The time for talking is over and you don't need to spend a lot of time getting their attention, whether that's a clapping or ringing a bell or whatever. However you choose to do that, have some signal that the time for talking is over, and expect that they will do that quickly.

Keeping Track of Papers

It's also really important with as many students to have methods of keeping track of their papers, especially if you expect them to do corrections. So I have a paper on my desk that has a spot for their math papers each day, and I keep careful track of when their math papers are one hundred percent completed, and I mark it off so that I can quickly look at the paper and see exactly who in the class still has work left to be done. Of course, sometimes they've handed it in and it's waiting on me at the time, so I don't always know that immediately. But I can always check up on that, and it really saves a lot of searching for papers and figuring out what happened.

I'm also very clear about the marks I will put on their papers when the papers are finished. So when they get the paper back, they know what to do with the paper. They know if they're supposed to put it away or continue working on it. It doesn't necessarily need to be the same for every class, although it can be a little confusing. I structure my English papers and my math papers a little differently, and it takes a little time in the beginning of the year for them to figure that out. But it works better for those two classes, so I do it and they do learn it after a few weeks with a little practice and a few reminders.

I'm usually very gracious with them at the beginning of the year as far as if they thought they were done and they're not. But then after I've taught them and they know, then I hold them to it. And so having some sort of system where you keep track of it and it's written down is really important. And while it takes a little time to do, it usually saves you time in the long run or saves you from having students who never get their homework done and you never realize it or never do the corrections and you don't realize it. So that can be very helpful.

Leaving Work in the Students’ Hands

Another thing I like to do is put as much of the work in the student's hands as I can, and depending on your school culture and your class and the dependability of your class, you can probably do more or less of that. I rarely hand out papers myself. I put them out at a certain spot on my desk. They know if the papers are there, they're ready to be handed out. I don't include quizzes and tests with that. If I'm going to pass out a quiz or test for some reason, I'll do that myself. We typically send them home. They don't actually get handed to them at school, so I don't need to deal with that. But I wouldn't do that. I don't want a student to see everyone's grades for something, but I do for their homework. I would do that. They can hand them out, and that saves me a lot of time.

Grading?

Another thing that I think can be done, if you have a lot of students, some teachers have a habit of grading a lot of papers, maybe more than necessary, something it's good to look very carefully at how many of the papers you're actually giving a percent grade and including on their report card. I really grade very few of their papers. They're testing quizzes are graded, a few math assignments are graded. I grade none of their English papers. And so they're handled in a little different way, and it saves me a lot of work. They are all checked. They all know they know which problems were done correctly and which ones were not. And we practice in class. But I don't count the practice for a grade, and that saves me a lot of time not needing to grade that many papers. So I would strongly encourage that. Generally, we don't like to be graded on our practice either anyway, and it often relieves a little pressure both for you and for the students if those papers aren't graded. Even though that's pretty standard at our school it's still a little hard for students. Sometimes they really want to know how many they got wrong on the paper. So it takes a little homework to teach them that it doesn't really matter how many wrong exactly. They should be able to look at the paper and see what they did wrong, and that's actually what's most important. But that saves me a lot of time. If I had to record twenty students grades in every subject for all papers every day, I would—I don't know—I would never do anything other than school. So that's really helpful to limit the amount. You need enough. You don't want to do too few. That can also be unfair, but you want to limit it to the point where students can relax and do their homework and not be worried about their grade necessarily. And it also saves you a lot of work as far as recording grades.

I have fifth grade, so I understand that for younger grades this is not possible. But as the students get older, the more checking that can be done in class is actually to their advantage. They are more aware of the problems they get wrong if they grade it in class then if you do. And so and it saves me a tremendous amount of time. I actually like to do a small section of math and check that before we even move on. And we will sometimes do that two, three, four, even five times throughout the class. It depends a lot on the lesson in some lessons. I don't do any of that just because of the time limit. If it's a long lesson, I will sometimes choose to not do any of it just simply to get the lesson done so they don't have so much homework. But if they don't understand the first section, and you don't realize it—they don't realize it—and you move on to something more difficult, sometimes they never catch their initial mistake. So it's a help to them. It's a help to you, and they feel kind of good about getting to the end of the day and having the majority of a paper finished. Most of it's actually checked already. They know how they did, and they know what to proceed with on their homework.

Involving Every Student

In class it can be difficult in a large class to get around and make sure that you include every student during class, so a few things that I think are really important. You may have possibly heard of the technique that is referred to as "cold call" when you simply call students without them raising their hands. I think that should be a very normal part of your class where students know that, especially in a large class, if a student chooses to never raise their hand, they can feel like they simply are not accountable for what's happening in class. So I call on my students whether their hands are up or not. Sometimes I tell them not even to raise their hands. Sometimes I do call and raise my hands, but I call on them, and they're very used to that. That doesn't usually take them by surprise. It's just a normal part of class so they know they can be called and whether their hand is up or not and it really helps keep them engaged. Other times I allow them to raise their hand and that keeps them engaged. But they really do need to be used to being called on, to being active part of class. In spite of the fact that they have nineteen classmates, they can't hide behind that. So however you choose to do it, you want to make sure that each student is involved in class as much as possible.

Students Who Struggle with Learning

If you have students that struggle with learning, you may need to be especially, I don't know, pay special attention to which questions you give them. Sometimes those are the students I give more questions, and at other times I may give them less, just depending on the subject matter and how prepared they are. But I do want to try to make sure I give them what they need. The students who do better typically don't need the questions asked, but it does make them part of the class, so I don't want to overlook them either. I try not to hold them, put them on the spot, too much, especially occasionally I'll say, "I'm sorry. "That was maybe a more difficult question then I realized," or I try not to hold them too accountable for something that I suddenly realized it maybe was too difficult for them, and they simply weren't prepared.

Beating the Blahs

February school days are their own kind of special. The holiday excitement has worn off, the days are still short and chill, and the school term is barely half-way done, with the second half stretching into the dim future. I sensed early in my teaching career that morale tended to drop to its lowest in February, and it became imperative to learn some good coping mechanisms. While I, too, was tempted to sink into apathy, I couldn’t indulge myself or I risked having my entire classroom slide into the doldrums with me.

The following list is comprised of ideas I tried in my teaching, with varying degrees of success. I have done some as a brick- and-mortar teacher, while others have worked better in a homeschooling setting. Certainly, we do not do all the things in one February!

- Pay attention to your clothes. Wear cheerful colors. This may seem like a no-brainer, but there was a reason why Soviet prisoners wore grey uniforms in grey prison buildings. Costume days for the children are lots of fun. You can earn all the mothers’ gratitude by doing this in a low-key way. Simply instruct your students to wear the brightest things they already own, in as many colors as they can layer.

- Switch up the routine. Once I selected a day to write all our subjects on slips of paper and inserted them into balloons. The children got to pop a balloon at the beginning of each study session to see what they would do next. This was more fun for the students than for the teacher, but it did keep me on my toes! You can also vary the ways you teach a subject. Instead of traditional spelling tests on paper, try a spelling bee, or learn states and capitals to a familiar tune. A day of novelty can be the break that everybody needs to get back on track with ordinary days.

- Decorate your space. It should be a place where students like to be. A string of lights hung on command hooks creates instant ambience when the weather outside is frightful. Light a scented candle or diffuse some fresh smelling oils. When my husband taught junior high, he bought some wing chairs and end tables at a thrift store and set up a corner for free-time reading, complete with a stereo for playing classical music at appropriate times.

- Invest in plants. Winter is a great time to force bulbs in a vase of water on the windowsill. Another simple project is sowing a handful of grass seeds in a shallow pan of potting soil for a tiny lawn inside. Children will expend great effort to earn the privilege of “mowing the grass” with a scissors, and the whole thing becomes a wonderful fairy garden base. Sprouting trays full of alfalfa seeds is another great way to almost instant gratification if you want to not only grow greens but eat them too.

- Buy or borrow some new books. Read-aloud time after recess was my favorite part of the day, both as a student and as a teacher. When energy is flagging, that is a great time to read a comedy or a mystery that makes everyone beg for another chapter.

- Do simple free-writing exercises in tiny notebooks. We have found some of the cutest little journals at dollar stores. The point is for them to not look like regular notebooks. Give your students five minutes to write on any subject you wish, such as “The Most Important Thing in my Treehouse,” or “If I Had a Hundred Dollars.” When the five minutes are up, they can quit writing. Nothing gets checked or graded. Generally, all it takes is one spontaneous writer sharing their paragraph for the contagion to hit the less enthusiastic writers.

- Tea and poetry is a perfect combination for dreary days. While this is considered a homeschooling classic, it could be adapted for the classroom if every child brings a mug and the teacher has facilities to boil a large pot of water. Brew and sweeten a whole pot to avoid sticky spoons and soggy teabags everywhere. Poetry read in this atmosphere is for simple pleasure. Read a bunch of limericks, a rhyming children’s storybook, or an epic poem. The wonder of words in cadence will lift even the droopiest spirits.

- Incentives are every teacher’s ace up the sleeve. I once bought a stash of tiny stuffed animals from a party supply store. Then I propped them all around my classroom and gave the students a list of challenges diverse enough that everybody had a chance, even if they weren’t academic stars. By the end of February, all of them had achieved at least one prize.

- Learn something new as a class. In my seventh grade year, a lady with the patience of a saint came to teach all the girls to crochet, and someone else taught the boys simple wood burning techniques. You can learn some fresh games, or a catchy song, or do a version of “Word of the Day” where you pick a new word out of the dictionary and explore its meaning. Bonus points go to any students who use it properly in ordinary conversation at school.

- Don’t forget to smile. I remember one grim mid-winter when I had heavy things on my mind, and I simply wasn’t feeling it in the classroom. To remind myself, I put smiley stickers all over my planner and made a point to actually look into each student’s face and smile genuinely every day. The atmosphere became lighter immediately and I recognized a universal truth: if the teacher’s not happy, nobody’s happy.

They say, “Variety is the spice of life,” and they are right. There is no need to have a clumpy porridge quality of life when cinnamon and cream are available! Sometimes we object to spicing things up for lack of funds, but imagination doesn’t cost anything. Given that most of us remember best what we learned when it didn’t seem like a lesson, keeping up the spirits in the classroom pays off richly in the long run.

Behind the Mask

“Good morning…uh…uh…uh,” I said to the girl coming down the hall. Her mask was over her nose. Her hood covered her head so only her eyes peeked out. Who is the girl behind the mask? “Uh…uh…oh! Carla, it’s you,” I said as she got closer. We chuckled together.

On another day, I greeted the girl going into the next-door classroom. “Good morning, Faith.” Dark eyes twinkled at me above the neck gaiter stretched over her lower face. A half-minute later another group of students trooped down the hall. “Good morning, Faith. Wait a minute, who was that I just saw go in the door?” because this really was Faith. Who was the other girl behind the mask?

I recall a student from years past who spent their school days questioning teachers, throwing out snide comments, and at times retorting disrespectfully when they were called out. This student was difficult to work with. Then I saw them in their home setting and I saw a different child. Who really was the child behind the mask?

Another child was quick to think I can’t. Yet, they could do it if it was of importance and interested them. Who was the child behind the mask? Did the mask cover up laziness? Or did the mask cover up a genuine inability?

This child is very quiet at school. Yet at home they come alive. Who is the child behind the mask?

This student is a clown. If life gets a little tense or they get backed into a corner the clown mask comes out and everyone has to laugh. But is the clown wearing a mask or not? Maybe not but then again, they may be.

This student went through school seemingly enjoying being the one who didn’t want to fit in. They went out of their way to break out of the expected mold. Their attitude seemed to be I’m going to get you before you get me. They always had a quick quip or dry comment to make. Who was the real child behind the mask? Because, in later years the mask began to slip and the hurting individual began to emerge.

I sat in the parent conference quietly fuming to myself. The accusation was unjust, the child of the parent just as much at fault as the child they were blaming. But with my mask of self-preservation in place, I found myself agreeing with the parents.

Today my students and co-teachers are wearing literal masks but every year we encounter students wearing figurative masks. As teachers, we put them on ourselves. Literal masks today impede our relating with other people. Our words get muffled, we can’t read expressions, and sometimes we don’t even recognize those around us. Likewise, the figurative mask keeps us from knowing the real person and the real issues. How can we see behind the mask?

Sometimes a mask is necessary. We expect doctors and nurses to wear masks in their work. A poultry farmer wears a mask to combat dusty conditions. Other occupations require masks. Currently, masks are doing some good in protection against infection.

As teachers, we should mask the frustration we feel with the student who isn’t understanding and isn’t attempting to understand. We should mask our distaste for cleaning up the mess left behind by a sick student who left his breakfast all over his desk. We should mask the impatience we feel when we are running behind schedule and students don’t understand how to move more swiftly. We should mask the initial sharp response we feel when our authority is questioned. A mask is a protection against a perceived unpleasantry or threat. Many times, bringing out our mask for a short duration makes our responses to unpleasant situations more Christ-like. But masks can also be detrimental. Masks can hide evil – think of a bank robber. Masks can be worn in a dishonest way.

Why do our students, co-teachers, and we ourselves wear a mask at times? The most obvious reason is that of self-preservation. Underlying that is often an issue of trust and honesty. We want those around us to think we have life under control, that we understand what is happening. We do not like to be uncomfortable. Putting on a mask is a way to maintain our image. As teachers, we do well to examine our motives for what we do and say and work to be honest in our dealings with others.

How can we as teachers see what lies behind our students’ masks? These days, when I get home from school, I put my cloth mask away. I’m in my safe place surrounded by my “bubble.” I don’t need the mask’s extra protection. I believe that gives us a clue on how to get behind the figurative mask that some students wear. We need to create a safe place for them. They need to know that we care about them as a person. We celebrate what they celebrate. We help them work through problems without getting frustrated ourselves. We lovingly correct them when they need correction. We work to become someone they can trust.

It is good to expand what we know about our student beyond the space they occupy in our classroom. Many times, I will talk with parents to get a better understanding of the child they see at home. It’s often not quite what I see at school. I want to know about their hobbies and enjoyments. Listening to lunch time conversations with their friends tells me a lot about what a child’s interests are. Getting to really know the child God created, building their trust in you, and granting them a safe place to go to school can help you see behind the mask a little better. Asking God to give you eyes to see each child as He sees them will also reveal their hidden faces.

Quite a few years ago, I was writing on the chalkboard, my back to the class, when one of my little first graders clambered up to me, gasping in her fright. I whirled around to see what was the matter and saw that a strange man had entered the open classroom door. He appeared to be an older man, but besides the fact that I had no idea who this person could be, something was wrong. The hands at his side and the legs did not match the Ronald Reagan head. They were much too youthful. My mother bear instincts rose to the surface and I hoarsely yelled, “Get out of here! You get out of here right now!” Immediately, the head mask was torn off and to my immense relief, it was only one of the older students in the school—a student with whom I had a very good relationship. While he hadn’t thought very far ahead, it had not been his intention to terrify me and my class. He was fairly contrite about it. Weak with relief, I admonished him, “Don’t you ever do that to me again!” Removing his mask brought the situation under control and revealed who the stranger was.

In many situations, if we take the time to see behind the mask our students present to us, we learn to know the real person and are able to speak to the real issues. May God give us wisdom to recognize who it is behind the mask.

When You Think You're Doing It All Wrong

Photo by Green Chameleon on UnsplashIf you�re on top of the world, this letter is not for you. Come back soon, on a day when you need it.

Dear Teacher,

I know you�re trying super hard. You started the school year with high hopes and good resolutions, but you�re feeling a little slumpy today, aren�t you? Maybe some of your systems didn�t work out, or took more maintenance than you expected. Maybe a child is resisting your best efforts to connect with him. Or you just can�t help another into the lightbulb moment she needs, in reading or subtraction or typing or obedience.

You might simply have too much to do, and feel important things are slipping through the cracks. Maybe you�re not getting the support you need, or your questions don�t have easy answers. Perhaps personal stresses are bleeding over into the classroom, and you feel you don�t have anything more to give.

I�m not even going to start on what might be happening with the school board, your relationships with fellow teachers, and the disturbed parents of the child you rebuked yesterday. I�m not going to mention the COVID health protocols and new ways of doing. (Oops. Too late.) Nor the fraught political scene, but I�m guessing your students have a few thoughts on that, don�t they? And might try sneaking them into history and lunch and recess, right after your brilliant devotional about being �in� but not �of� this world?

Believe me, I know you�re up against a lot this year.

Perhaps you worry you�re doing it all wrong, and that serious harm will come from your best efforts � not to mention your worst mistakes.

So.

Let me tell you a mathematical impossibility, for starters. It�s impossible to do it ALL wrong. Let�s just clear that up right now. Some of the things you are doing are truly making a difference, and I don�t think you can step back far enough to see yourself and the hopeful changes you�re bringing. The children are better for having known you. (I mean, statistically this is likely. I don�t know you, but I�m sure at least half of them are glad they do. Can�t speak for the other half.)

Are you still able to laugh? Give thanks for this.

Second, it�s not only mathematically but also spiritually impossible to do it all wrong. Have you heard of the Redeemer, the great Second Chance Giver, the Savior? Do you know He is fully capable of arranging the evils and inadequacies of this world to accomplish His glorious purposes? Even if you were deliberately trying to do wrong, you couldn�t ruin His plans. And you are trying to honor Him, welcome His little ones, give sacrificially of yourself. You are in Him, and your success is not dependent on your performance, but on His goodness.

�For the word of the�Lord�is right�and true;

he is faithful�in all he does.

The�Lord�foils�the plans�of the nations;

he thwarts the purposes of the peoples.

But the plans of the�Lord�stand firm�forever,

the purposes�of his heart through all generations.

Psalm 33:4, 10-11

Third, there are resources that can help you. Reach out for them. If it�s just a droopy evening, find a large mug of hot tea and some refreshing music. If it�s a hard week, get some good sleep and great protein this weekend. Spend time with somebody you love. If you�re regularly coming home discouraged or exhausted, day after day, talk to someone. See if you can outsource a few pieces of your job, cut a few extracurriculars, take regular times to recharge. Or seek additional training in your particular place of uncertainty. Your pastor and a YouTube tutorial might do the trick. It seems astonishing, but people can change. You can grow to become capable of things you weren�t before.

You�ve got this. Or more accurately, He�s got this, and He set you in this place for a reason.

�We wait�in hope for the�Lord;

he is our help and our shield.

In him our hearts rejoice,

for we trust in his holy name.

May your unfailing love�be with us,�Lord,

even as we put our hope in you.�

Psalm 33:20-22

You�re doing fine. It�ll be okay.

Best of blessings,

One of the moms

Getting Our Students Outside Every Day, Part 1

I spent eight years teaching at an Anabaptist school; and to be honest, the least favorite part of my winter days was outdoor recess. Granted, after I got all my first graders as well as myself bundled up, the sun and crisp air DID feel refreshing. Upon returning to the classroom after twenty to thirty minutes, the rosy glow on my students’ cheeks showed that the moments outside had not been in vain. Still, even though I could see that outdoor recess had been good for us all, I continued to see outdoor recess as more of a discipline than a joy.

Most of the school patrons understood that outdoor recess was a normal part of the school day. They sent their children to school dressed in warm layers. Occasionally, there was that parent who would request that their child remain indoors due to asthma or a head cold. But for the most part, the parents seemed supportive of having their child play outside.

While I was teaching in the public school setting as well as helping at a community daycare I learned that teachers in America are not permitted to allow outdoor recess when temperatures dropped below a certain point. In fact, there was much that was not permitted outdoors. If the sidewalks or blacktop had ice, the children needed to stay off of them. Children playing around could lead to accidents with broken limbs which could lead to lawsuits. Also, much of the recess equipment such as monkey bars, balance beams, and sea-saws were off limits until a certain age for fear that a child might injure themselves. There were strict rules on the playgrounds that varied from “no going up slides” to “no running.” The teachers were not trying to punish but rather to keep accidents from happening that could end up getting themselves or the school in trouble.

Then I started having children of my own while living in an urban environment. For us, outdoor play needs to happen at the park, on our sidewalks, or within our tiny backyard. Because my boys both love the outdoors, we try to get out regularly. It is common for us in both the cold months and the hot summer months to be the only children at the park that we frequent. These days, we rarely pass other children on the sidewalks. And we live in a city where the children are not able to attend public school in-person due to COVID-19 concerns, which means that they must all be staying inside their homes or at a daycare.

America’s View of the Outdoors in Contrast with Other Countries

Counties within the Scandinavia such as Sweden, Denmark, and Finland have even colder temperatures than America but respond quite differently to outdoor activities than American teachers do. In Finland, students typically get a fifteen-minute break after every lesson which ends up being a total of approximately 75 minutes of break time a day. Many teachers in Scandinavia use the school yard and nearby nature areas to teach math, science, history, and other subjects on a regular basis. According to the Danish, the concept of teaching students outside the school is called “udeschole,” or outdoor school. They see it as a way for students to build a relationship with their environment and get in contact with nature during the school day. According to Anders Szczepanski, the director of the National Center of Environmental and Outdoor Education at Linkoping University in Sweden, “Studies show that if you alternate outdoor and indoor learning, and the teacher is prepared, you get good results.” (141-142)

Scandinavian parents, too, seem to see messy, wild, outdoor play as perfectly natural. Going outside in any type of weather with their children is probably a reflection of a belief that being able to cope with all types of weather will make their children more resilient. (p.192) No weather is so bad or a mud puddle so big that cannot be conquered with good coveralls, waterproof mittens, and fleece-lined boots. With the proper gear, both adults and children see going outdoors as the norm rather than the exception to the rule.

A Call to Reflection and Evaluation

Is “indoor children” a growing trend within America? And if so, are we unknowingly having the children within our own families and schools spending more time indoors than they did a hundred years ago? And if so, is this a trend that we want to embrace as Anabaptists? Most of my research within this article is due to McGurk’s research in her book, There’s No Such Thing as Bad Weather.Stay tuned for a following post on both the benefits of the outdoors on a child’s health and body development.Sources:

Is “indoor children” a growing trend within America? And if so, are we unknowingly having the children within our own families and schools spending more time indoors than they did a hundred years ago? And if so, is this a trend that we want to embrace as Anabaptists? Most of my research within this article is due to McGurk’s research in her book, There’s No Such Thing as Bad Weather.Stay tuned for a following post on both the benefits of the outdoors on a child’s health and body development.Sources:MCGURK, L. K. (2018). THERE'S NO SUCH THING AS BAD WEATHER: A Scandinavian mom's secrets for raising healthy, ... resilient, and confident kids. SIMON & SCHUSTER.