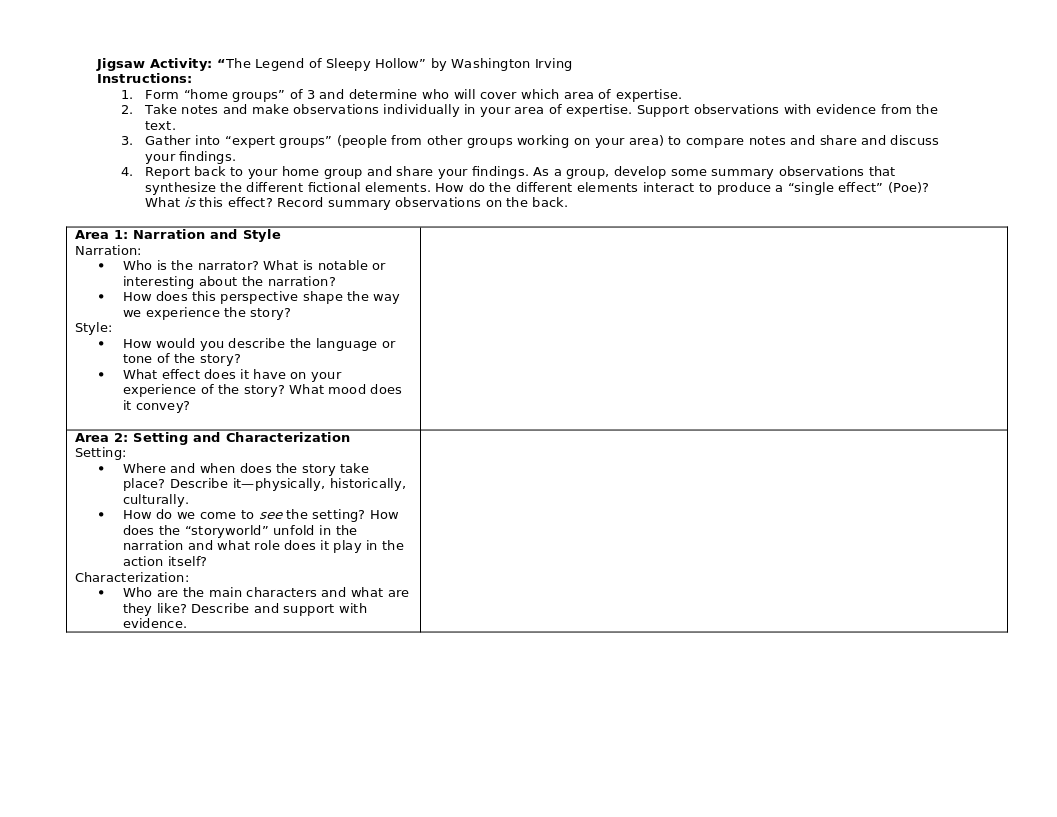

All Content

It�s May! Summer is Coming!

While I do love teaching and enjoy my job greatly, it is stressful being responsible for little humans all day, and one of the perks of being a teacher is having the summer �off.� (In many ways, it�s not really �off,� because we usually find ourselves preparing, planning, and participating in teacher enrichment types of activities.)

So, May is here and summer is coming. What will you do with your time off? Here are several options and suggestions for ways you can spend those precious three months you�ve got coming up soon.

Rest and relax. We are responsible for our students about seven hours a day, and that can be stressful even if we really enjoy what we do. If you�ve ever been a secretary, cashier, or builder, you know the difference. Take a few days or a week to just relax and spend time doing things you love to do but don�t always have time for during the school year.Set some educational goals for next year. I look for the area I�m weakest in and work on that. One year it was teaching science, another year it was art, and this year I think it�s going to be organization. Read books, research and get ideas, ask other teachers questions, and work on improving that area of need.Plan some teacher enrichment activities. This is always one of my favorites. I plan to go to seminars, camps, museums. I usually try to travel to at least one new place. I want to have more knowledge and experience next year than I did this year. I want to have more interesting stories to tell my students, and I want to model for them what it�s like to be a lifelong learner.At the beginning of August (or earlier if you�re ready and in the mood), go into your classroom and gather any new books you�ll be using. Plan to take them home where you can look them over at your leisure. Sit at your teacher�s desk for a while and look around, visualizing where you might move desks, furniture, or a bookshelf.Gather materials. Go through the science book and gather everything you will need for every experiment and put it in a bin to take to your classroom later. I also try to find brain games, interesting books and puzzles, or science or history items to add to my classroom.Plan and prep. About two weeks before school starts, I like to make sure I have my ducks in a row. I double-check all the books and tests and make sure I have everything I need. I like to figure out how many pages I would need to cover in a day in order to finish the books by the end of the year. I�m not a �book finisher,� and I will gladly stop, slow down, or back up if my students are not comprehending what I�m teaching them, but I have found that usually we can indeed finish our books on time if we stay on track and focused all year round, and don�t get sidetracked with all kinds of bunny trails and waste time in class.The summer months fly by, but if we have a plan, set some goals, and use our time wisely, we can make the most of them. We can feel relaxed, refreshed, organized, and ready to go in August if we spend our summer months well. Happy summer!

Prayer for the End of the Term

I’m tired, Lord.

As our year winds down, we are all tired and weary. I’m weary of drilling math facts. I’m weary of listening to halting readers. I’m weary of checking books. And I am weary of the constant struggle to maintain an orderly classroom and to teach classes in an orderly manner. You know the circumstances surrounding this year and the struggles we’ve encountered. You’ve given fresh courage and the break-throughs we needed, time after time. And, now we need you yet again.

It is so easy to respond to students’ frustrations with frustration of my own. Give me the calmness to deal with the reason for their frustration in an appropriate manner. Guide me in helping the child who needs to learn perseverance when they meet work that, at first glance, looks too hard. Show me when a child is truly confused. Help me to discern when the child wants a crutch and to soften my speech with grace. Grant me wisdom in dealing with the child who pays attention to everything but the lesson I am teaching.

It would be so easy to give in to student sighs and skip the math and word drills. Give me the patience and the enthusiasm to relieve the sighs and frowns without eliminating the practice. Help them and me learn to persevere.

And, the temptation to nag and scold rather than deal with the problems is great. Give me the clarity to see the issues for what they are and the fortitude to address them wisely.

Lord, help me to see each of these children, not as problems, but as children with an eternal future. The habits they are forming now help shape who they will be. Direct me in my part of developing their habits. I want them to be productive, respectful, and upright adults who are willing to work in your Kingdom. But often the moment is foggy and I’m uncertain of the wisest response.

Lord, thank you for the good times we’ve had together. We’ve read together, played together, laughed together, learned together. Thank you for supportive parents, administration, staff, and board. Thank you for placing qualified aides in my classroom, aides who see what needs to be done and can go ahead and do it.

And, while at times I feel little progress has been made, I look back to the beginning and see that there has been progress. Sometimes a lot, sometimes it’s just a little, but it’s there. Thank you, Lord, for every step of progress I can see.

These children will soon step out of my classroom for another room and another teacher. A bit of my heart goes with them. Lord, walk with that teacher. Grant them the wisdom to lead these students well. Go with these students. Keep their hearts tender towards you. They have many abilities and talents. Help them to find the way to use their abilities to build your work. Take their weak spots and turn them into strengths in your kingdom.

There are just a few weeks left. I look back gratefully at all you’ve provided during this year. We continue to need your strength and wisdom to finish well. Walk with us these last days.

In the name of Jesus, Amen.

The Joys and Challenges of Teaching Generation Z Students

I began teaching before everyday Americans had computers or email in their homes. I remember when students had to get books from the library or use encyclopedias to get information for reports, and when students handed in papers which were either handwritten or typed on a typewriter. Things sure have changed. While there are positives and negatives to just about any situation, it is good for us to recognize, learn, and make the best of where we currently are. Here are some suggestions regarding teaching and education with Generation Z students.

A Joy: Students are sharper and can process information much faster.A Challenge: Class can be incredibly boring for them.Students are used to having a myriad of information literally at their fingertips, are actively pressing buttons, and are often looking at pictures and watching videos on their computers or phones.

How should we as educators deal with this?

Keep our classes moving along and not boring. Show pictures, tell stories, and keep the students participating in classes. Ask questions, let them work in groups, make them laugh, think hard, and complete hands-on projects or assignments in class. Variety is great.

While we shouldn’t be expected to entertain them, if we just lecture in a monotone voice, we cannot expect them to learn much. I once had a class that was either asleep, or a little too rowdy for my comfort level. I found that I could keep complete control and have most of them tune me out and go to sleep, or I could keep their attention by being myself and having them laugh a little, even though it was a bit harder for me to keep them completely quiet – and I need to have quiet to teach effectively. I chose the latter. We did laugh and learn, even though I did have to get on them about their behavior more than I liked to.

A Joy: Students have access to much helpful information.A Challenge: Students have gotten lazy because tons of information is literally at their fingertips.I have heard stories of students literally cutting and pasting entire paragraphs from their supposed “research” into “their” reports. This is an atrocity. First of all, students need to be taught how to think and write in English class, and then should be practicing this skill in other classes as they progress through school.

This is a completely different subject, but the remedy for this problem is similar: We teachers need to lead them through the process of researching and taking proper notes in class and help get them started and comfortable with the process, especially in middle school, and they don’t need computers to do it. I don’t let my students have an open computer in class until all their notecards are finished and we begin to write rough drafts.

For most writing assignments, I recommend having students write down ideas in class and then organize these ideas into a short outline. Then I have them hand it in before the end of class. This forces them to think and compile a few ideas to get started.

Students should also be kept accountable by having to hand in outlines, research note cards, and rough drafts along the way. This also helps them from procrastinating and being lazy.

While there is no guaranteed way to prevent students from plagiarizing and not doing their own work, we teachers should hold them accountable and do whatever we can to encourage them to do their own work. Use plagiarism checkers, or look up anything that doesn’t look or sound like your students own writing. If you find it, print out the plagiarized document and highlight the sections in both the students “writing” and the plagiarized document so that you can show and explain this to the offending student. This will make it a learning experience and keep them accountable.

The Joy: Students’ grammar and spelling are much better thanks to spell checker and grammar correcting programs.The Challenge: Students aren’t finding the mistakes on their own through editing because the computer is doing it for them.However, those little squiggly underlines alert them to the fact that something is wrong, and they have to act upon it to fix it. Even if the program tells them how to fix it, they still have to see that what they did is incorrect, look at the correct option to fix it, and click on it to correct it. Although it would be ideal for students to identify these mistakes themselves, computers are here to stay, and they do point out these mistakes to the students. Perhaps all this will save us time grading those research papers?

April 2022 Progress Report

In the first quarter of 2022, we worked to improve the layout of the home page and improve the visibility of high quality content. Most of these changes have not yet been published, but are due to be released soon.

We are grateful to have added contributions from several new bloggers, including Karen Birt and Rosalie Beiler.

Next steps to be taken include improving the search experience, tweaking the home page, and making curated content more visible to users.

If you or someone you know has produced classroom materials, board documents, or administrative policies that could benefit other schools, share them here! Bring your questions and ideas to Conversations at The Dock.

Five Go-to Practices to Energize Your History Class

History is actually a class where we learn about real people and true stories about what they did. It should be fascinating—not boring. Here are a few ways to make history more interesting for your students.

- Show actual pictures. Photos of the Native Americans, the Great Depression, suburbia in the 1960s, the Twin Towers, and anything since cameras were used in the mid-to-late 1800s are great. They speak volumes to students and make more relevant what the students are reading in the textbooks. Use drawings when pictures are not available.

- Discuss the reasons for what people did and why they did it. Most of what occurred in history was done for greed and power. Talk about what God’s Word says about this, and what the response should have been. Was the Civil War really the only way to end slavery? Discuss how whatever you are studying relates to us today. We are currently studying the American Revolution. We talk about how the colonists had said that they would obey King George and didn’t. Then we talk about who we should be loyal to today. When we get to studying westward expansion, we will discuss what people might do today to start their lives over.

- Put the students into the scenario being studied. If you are studying the Great Depression and read that around 20% of the people were unemployed, apply that to your class. If you have ten students, two of them wouldn’t have jobs or any income. Ask what we should do as Christians to help them.

- Complete projects in class that directly relate to what is currently being studied. Construct buildings out of popsicle sticks, replicate art forms from different cultures, eat foods from different countries, make string art maps of continents. I have compiled a list of over fifty projects for American and world history, most of which can be completed in the classroom in one class period. Contact me if you’re interested and I will gladly share it with you. (littleflock7gmailcom)

- Read and discuss the text together as much as possible. Have students read paragraphs and digest the content together, asking them questions and discussing what happened. It is also helpful to have them write down key concepts, take notes if they are older, or label diagrams or worksheets with as many visuals on them as you can for younger students.

Jump-start Your Bible Class with These Five Tips

Bible class is the most important class we teach. How can we make it come alive for students? What can we do to keep students� attention, keep them involved in class, and help them apply God�s truths to their lives? Here are a few suggestions.

- Maps, maps, maps! Get big maps and post them on the walls. Point to them and show the students where things happened. Get little maps and have students color them as you are studying about that particular area.

- Have students read the Scripture passages aloud, one verse per person. Have them all open their Bibles and follow along. Get a stack of small cards or popsicle sticks with their names on them, mix them up often, and call out the name of the person who will read the next verse. That way students will never know who is next and will have to be paying attention.

- Make it practical. If you are studying idols, ask students how we make idols today. We don�t bow down to golden cows, but how much money do we spend on cars or hobbies? Could those be idols to us?

- Show pictures or bring in items for every noun that is unusual. Examples: leeks, pomegranates, shofar, ephod, showbread, oil lamps, etc. Bring in some showbread, burn an oil lamp, or eat leeks and cucumbers.

- Celebrate the Hebrew feast days and holidays.

Have a shortened version of the Passover for lunch one day, or a longer one in the evening if possible. Study it ahead of time so that students will understand what each part represents to Christians. Observing the Jewish holidays and learning the significance of each is educational and fascinating, and it can really liven up your classes. Following is a list of the Jewish holidays in 2022 with ideas of how to celebrate them with your students.

- March 17, Purim: Read the book of Esther and celebrate God�s deliverance of the Jews; eat Hamantaschen (Haman's hat cookies) and give money to the poor.

- April 15, Passover: Read a shortened Christian Passover Seder to remember when the angel of death passed over the Israelites but killed all the firstborn of the Egyptians. The Passover meal includes a lamb shank to represent Jesus as our Passover lamb, horseradish as the bitter herbs of slavery, unleavened bread as the Israelites didn�t have time to let their bread rise when they fled Egypt, charoset to represent the mortar used in brick building, salt water to represent the Israelites tears, and more.

- September 25, Rosh Hashanah: Celebrating the Jewish New Year, time is spent in repentance and prayer. Challah bread and apples dipped in honey are eaten to represent God�s provision and the hopes of a sweet year to come.

- October 5, Yom Kippur: The Day of Atonement is recognized on this holiday, and this was the one day in which the high priest would enter the Holy of Holies in the temple. As described in Leviticus 16, two goats were brought to the temple. One was sacrificed. The priest would place his hands upon the second goat, listing the sins of the people, transferring their sins to the goat. Then the goat was set free in the wilderness as the scapegoat, just as Jesus took our sins upon Himself. It is a day of fasting, usually for twenty-five hours, and fervent prayer. Forgiveness should be asked of anyone to whom it is due. One hundred soundings of the shofar signal the end of this holiday.

- October 10, Sukkot: The Feast of Booths is commemorated by building temporary booths or tents to remember when the Israelites lived in tents while they wandered forty years in the wilderness. These are usually decorated with fruits and vegetables. Class could be held in the tent for the day.

- December 19-26, Hanukkah: This holiday celebrates the Maccabees� successful battle against the Syrian-Greeks who had desecrated the temple. They re-lit the eternal light and one day�s oil miraculously lasted eight days, hence the seven candles on the menorah.

Making Teaching Sustainable Long-Term

�How do you keep teaching year after year without burning out?� Occasionally I hear this question from friends and colleagues. My reply varies somewhat depending on the listener. To be honest, I have often asked myself the same thing, and I am far from having all the answers. Yet I have recognized some life principles that have sustained me through sixteen years of teaching, and I am still learning to put these things into practice well. Beyond the obvious factors of maintaining my relationship with God and doing what I can to stay healthy, here are some things I have learned:

Learn to say no to good things. Christian school teaching is a high and holy calling, and it deserves our loyalty and energy. You may have struggled, as I have, with attempting to find your identity and self-worth in your involvements and accomplishments. It can be difficult to learn to say no to ten things so that you can do one or two things well. Teaching school long-term means that you will need to turn down other good opportunities.Recognize and embrace the value of deep commitment to a community. Deep-rootedness produces beauty and strength. Teaching school provides us with an opportunity to invest deeply in the shaping of our churches and communities, and this is a beautiful thing. Recognizing and appreciating this provides a sense of purpose that can help us through the difficult times. I have enjoyed the privilege of having some of my former students become my fellow staff members. On Sunday morning I smile as I see former students teach Sunday school, lead singing, or have devotions. Currently I teach the children of many of my former schoolmates. While the restlessness of mainstream culture can lead us to believe that fulfillment comes from trying new things, jumping from one community to the next, always looking for the next exciting opportunity, nothing can replace the value of deep roots and commitment.Teach out of who you are, not out of what you think others expect of you. It is far too easy to fall into the trap of trying to live up to everyone�s expectations. These expectations can be real or only perceived, but becoming obsessed with them swiftly leads to burn-out. While you will always need to follow basic expectations of your school and community, you must shape your classroom around your own interests, talents, and teaching style.� Don�t think you have to do everything that other teachers do or that previous teachers in your classroom did. I think of a classic example of this in the school where I teach. Many years ago, a teacher got her fourth graders involved in a chick-hatching project. She had grown up taking care of animals, and this was her interest and passion. She taught for a few years, and students always looked forward to this project. Teachers who followed her didn�t want to disappoint the students, so they continued the project whether they liked it or not. It became a tremendous burden for some, until one teacher finally had the good sense to discontinue the tradition. This freed her to incorporate other things that capitalized on her own talents and experiences.Invest in your own continuing education. This may involve taking a few college courses while teaching or even taking a few years off to pursue more education. While that may be out of reach for some of us, many simple tools are available to anyone. Read books. Travel if you can, especially to places with historic or educational value. Do things that stretch you. While I was with a group of other adults, learning a skill that was difficult for me, I found that I could suddenly empathize better with students who struggle in my classroom. As we teach, we must be continual learners.Simplify your lifestyle. This can mean different things for different people. Something that is an enjoyable hobby for one person can be an energy-draining burden for someone else. For instance, having an extensive wardrobe and putting together a unique outfit every day may be something that gives you joy and energy. I, on the other hand, have found that a fairly simple wardrobe works best for me and that my decision-making powers are best saved for other endeavors. What can you eliminate from your daily routine without compromising something that you value?Make time for things you enjoy that have nothing to do with school. This can be tough, especially in the first year or two of teaching. School responsibilities can feel all-consuming. This can also perhaps seem to go against the previous point. But I believe it is vital to have interests and hobbies outside of school and to avoid having teaching become our identity.Teaching long-term without burning out is possible. The stability of years of experience in the classroom is something that our schools and communities desperately need. Will you do what it takes to offer this to your community?

Quick Ideas for Improving Reading Comprehension and Reading Fluency

Many of us remember those days in the learning-to-read process when we read aloud haltingly, sounding the words out and maybe guessing what the words were from the first letter. In a classroom setting, we counted the students ahead of us to see which paragraph we were going to read. Or maybe we were the other student, the one who could read quickly and disliked waiting on slower classmates.

Most of us moved beyond the halting reading as we became proficient readers. But some students never do. Even on the high school level, reading fluency and comprehension can be an issue for some students. Fluency refers to the ability to read with accuracy, proper speed, and appropriate expression, while comprehension encompasses understanding and interpreting the content of what is read.

If you have students who struggle with reading comprehension and fluency, here are some tips for you.

- Have the student mark the text as they read. Use a highlighter (or sticky notes if the book needs to be re-used) to point out the important parts. This works especially well for reading in content areas such as science or social studies where the important facts need to be remembered for a test. (reading comprehension)

- Annotate the text. In the margins, write thoughts, questions, connections, pictures, or graphics of the main ideas and the important details. This is similar to the tip above, but involves doodling or writing in the margins. If the book needs to be used again, the teacher may need to make copies of the pages for this one to work. (reading comprehension)

- Listen to audio of reading while following along visually with the text. This works well to teach proper vocal expression and timing of reading (make sure the audio reader has good expression). (reading fluency)

- Take turns reading aloud with a partner. Preferably, the partner is someone who reads aloud well. For an especially struggling reader, it may help for the partner to read a longer passage before the struggling reader reads a shorter passage. (reading fluency)

- Do repeated reading with a partner. With this, a partner reads the passage aloud first, with the second person reading exactly the same passage aloud again. The first reader should use proper expression and speed of reading. You can combine this with point #3: a single reader can listen to an audio reading, pause the audio, and read it again himself. (reading fluency)

Recommending Help Before A Child is School-Age: Our Experience and Addressing Frequently Asked Questions

Our experience

When I noticed that my two year old was not speaking as clearly as his older brother had at his age, I decided to call for an evaluation by the Early Intervention team in our area. A date was scheduled for the team (a physical therapist, a speech therapist, and a special education teacher) to come out to our house to interact with us. While the physical therapist and speech teacher interacted somewhat with my two-year-old, they soon saw that there were no concerns within those areas of his development. His speech, on the other hand, received the majority of their evaluation. However, after tallying up the composite score on his speech assessment, he technically did not qualify to receive services because his high scores in the areas of �social communication� and �receptive language� skewed the lower score of �speech clarity.� In other words, because he was able to understand what was spoken to him, follow multi-step commands, point to objects, and get his point across, those strengths compensated quite a bit for his lack of clear output. Technically, he did not NEED speech therapy.

At this point, the team seemed to gauge my opinion as a parent. Is his lack of clear speech causing him frustration? Is it causing the family frustration? Is it frustrating to people outside of the home? Would the mother like to have more tools with which to help him develop his speech? After they determined that we would really appreciate the speech therapy for our son and tips and pointers on how to work with him on developing clarity of speech, they put in a call to their supervisor and asked if they could pull out the lower score of �speech clarity� and make an IEP (Individualized Education Program) for our two-year-old�s speech clarity in order to provide services for him. After consent, they wrote up several goals for him to achieve within a quarter of a year. As the quarter nears, his progress on the goals is assessed and new goals are written.

As part of the Early Intervention program, the speech therapist visits the home weekly. After the initial evaluation, we were asked what day of the week and time of the day we prefer. Upon hearing our preference, they lined us up with a speech therapist who had a similar opening in her schedule.

Since Early Intervention in our area transitions to IU13 once a child turns three, they have helped us to transition into IU13 (these Intervention Units differ in name across the state and country) which is designed to give students instruction within our local school system. Again, we had an initial evaluation, asked if we want the services, and set up an instruction time. The main difference in the IU13 program is that I will need to take him to their office (about three minutes from our house). This instruction time slot each week is a half hour and more instruction-focused, less play-focused. As the parent, I can either take the rest of my children along and wait outside the room or leave them with their father and accompany my son into the instruction area.

How much time does early intervention take out of a family�s daily schedule?

For us, a typical speech visit is about an hour in length; and it includes chatting with the parent on how the child�s week was, interactive play with the child, and speech instruction. While the speech therapist gives a short section of speech instruction each week, it is really throughout the week that the parent needs to take the time to practice what was learned/ worked on during the time with the speech therapist. This can be typically be completed with a few focused minutes throughout the day and within your normal day-to-day communication with your child.

What is involved in signing up for Early Intervention?

�You simply have to call the number to get the ball rolling. Google �Early Intervention in (the name of your state)� for the phone number. Each state differs a little in the way they handle Early Intervention but all states are required by federal law to provide a free developmental screening and evaluation. Depending on your state, the services the child qualifies for may or may not be free as well.They wanted a report of a recent wellness visit from my child�s doctor, a copy of his birth certificate, and signed forms. As with any government process, there are a lot of legal forms such as parent consent, authorization to release information, parent�s rights agreement, and permission to evaluate and then re-evaluate. If you live in PA, you can find all the forms (and many that won�t be needed for your specific case) at this website.

I did not find the paperwork or signing up process to be cumbersome. The secretary was most helpful and was not overly concerned that I did not have his birth certificate since it was enroute to the passport office at that time.

Can any concerned adult refer a child?

Not exactly. While a healthcare provider or other professional can refer a child to Early Intervention, the parent or primary caregiver is the only one who can give consent for evaluation and services.

Is earlier better than later?

Yes, according to studies, the brain is the most malleable within the first three years of life. You want to try to catch any type of learning disability or difficulty as young as possible.

However, late is still better than never. If you have concerns about a child�s development, it is never too late to reach out for an evaluation. The public school system is required to give a free evaluation up to 18 years old. While they are not required to provide free services for you if you choose to enroll your child for private education, they are always required to give all students free screenings and evaluations. You can then use that recommendation or evaluation as a starting point with the teachers/tutors in the private school your child is enrolled in or you can hire private services/tutoring at the location of your choice.

How do you approach a parent about concerns you have for their child?

If you are a teacher, you know there is a delicate balance between supporting a family without usurping the authority or responsibility of a parent. It is the parent�s main job to care and provide for their children. The teacher is to walk alongside them and assist in the educational role. In a healthy family situation, a parent will know their child better than any teacher will. However, the teacher has a unique perspective as they see many children enter their doors year after year. Because they have seen multiple children from multiple homes in academic situations, a teacher can often spot or sense a disability or lack of development in a certain area before a parent may be aware of it.

As a community of people who are all working together to � better equip the next generation for God�s work, we all have a responsibility to speak into those lives. Here are tips for teachers for approaching a parent about concerns you have for their child:

- It is not about the parent. Approach the parent with the belief that the disability or lack of development is not the fault of the parent. Many parents are providing a home environment that is stimulating, language-rich, and engaging. A parent can be doing all the right things and a child can still have a disability or lack of development in a certain area. Assure the parents that the disability or difficulty the child is experiencing is not a result of something the parent did or did not do.

- Normalize the situation. All children have weaknesses and all children have strengths. Because we want to all children to learn to maximize their strengths and minimize their weaknesses, we give them tools with which compensate or overcome their weaknesses. We give glasses to the visually-weak, we give vitamins and supplements to the immune-weak, and we give training wheels and pull-ups to �children in training.� Would it be possible that this child could benefit from a little extra help that would help them to feel more confident in an area of difficulty?

- Give the parent hope. Often the parent may have a niggling feeling that their child is weaker in a certain area, and they may have been worrying about it before you ever approached them. Have you seen other children struggling who then received tools they needed to overcome or compensate for that difficulty? Do you know of anyone who has had a successful experience with Early Intervention? Or was tested by the public school system and now can use those recommendations and accommodations in the classroom for a less-stressful school experience for the child? Or that struggling child in your first grade whose parents took him for intensive therapy and by the end of second grade had risen to the top of the class?

- Speak your opinion but support the parent. As much as you may think you are right in your belief that the child would benefit from additional intervention, you are not the primary caregiver that God placed over the child. In the end, it is the parent�s choice whether to pursue the route that you recommend. Speak clearly. Speak with love. And then leave it in the parents� hands.

Is Early Intervention more headache than it's worth? What are the pros and cons?

Pros

- One-on-one instruction for child with a teacher. My child learns to interact with another authority figure and practices sitting attentively and interacting appropriately for an hour a week.

- Tools for the parent to use in future situations. I learn from the therapists even more than my child does; I am adding the tools to my tool bag that I can use in possible future situations with other children.

- Opens our home to more people from other backgrounds of life. I do not have to leave my house to be a godly influence in my world; the therapists and professionals are coming to me and see us in our natural home environment.

- More adults investing in my children. My children are blessed with so many caring, loving adults who want to see my children succeed.

- Accountability for parent to practice with child. When you have someone checking up with you each week on how the week went, you have an incentive to take those daily ten minutes to practice throughout the week.

Cons

- An additional �to-do� to add to an already full life. Mothers are already sacrificing precious amounts of personal time to change all the pampers, prepare all the food, and keep up with the daily washing. Finding the time to practice even ten minutes a day may seem overwhelming.

- Government hand-out. It has been said that the more we accept from an entity, the more control they can exercise over us. It is certainly true that if they ever ask us to compromise Biblical values in order to receive their services, we need to refuse their services. In addition, we need to realize that the government can choose to withhold services from us at any time.

- Managing the rest of your children while trying to focus on the therapist. Like myself, many mothers are trying to still care for their other littles while the therapist is working with the child receiving services. Helping my four-year-old not to feel �left-out� while his two-year-old brother is receiving the attention from the therapist as well as keeping my one-year-old from ripping the papers/activity pieces/game into shreds and still trying to communicate with the therapist and pay attention to the skills being taught, is not for the faint-of-heart.

Has it benefited us?

Yes, my two-year old has made significant progress in his speech clarity. Typically, when he has mastered a sound or other clarity concept during focused practice time, it will take about three to four weeks before I hear him use the concept/sound correctly in his own speech while playing or in other casual conversation. For example, he has had trouble saying his brother�s full name �Cameron� and would use the name he has called him since he first began to talk: �Fam.� About two months ago, he started correctly saying �Cameron� when we practiced with him. But it wasn�t until about a month ago that he was trying to get his brother�s attention while his brother was on the back porch by calling him �Fam.� When his brother didn�t respond, I heard him switch and say �Cameron.� His practice had finally transferred into learned behavior. In Early Intervention, you do not typically see immediate progress; but yes, in the long-term, he has made significant progress.

Would have he made this progress without Early Intervention? Possibly. I do not know. We do not have a clone of our son that we could have given one the services of Early Intervention and not the other in order to conduct a true science experiment. But we are grateful for the service, and recommend it to others!

In a Rut?

�Time for Heggerty!� I say cheerfully even though I am tired of Heggerty*. Moans and groans come from the first graders. We are all tired of Heggerty!

In math class, I look around and see several children sitting listlessly, some with their heads down on their desks. In other classes I notice that the writing and coloring is not as neat as it had been earlier in the year.

Are we as teachers stuck in a rut? Where is our motivation to teach and learn and do our best? It has been a challenging winter, with a long stretch of no breaks since we didn�t have snow days or any scheduled days off. Easter is late this year, so we are still looking forward to that break. The weather was not exciting. We�ve had a lot of hard things to deal with.

How can I motivate my students? How can I motivate myself? Sometimes I feel like I am just shoving papers at the class�here�s your math fact page, here�s your math page, here�s a seatwork page. I think of a teacher I had in high school. This teacher handed out English worksheets, then dusted the counters, sat at her desk and filed her nails and balanced her checkbook while we worked on the worksheets!

I believe my students are tired. I think, do we have to do every worksheet? (No.) What can we do for independent work that is different than just worksheets? What can we do during group times?

I am tired. I think, do I have to grade every worksheet? (No.) What can I do to motivate myself and my students?

For myself, I can go out and take a walk before I start grading or lesson planning. I should get some fresh air and enjoy the flowers beginning to bloom. I can take a break in my work and enjoy that beautiful sunset. I don�t have to grade every paper. Someone advised me to give myself grace.

For my students, I can find activities other than worksheets. They can type their spelling words, write them with chalk, paint them, or illustrate them. Our morning work time (or independent work time) might be to read, or do XtraMath, or make a card for someone. We can do learning activities and not just busy work.

One day the electricity went off at school and the report was that it wouldn�t be back on for hours. We put the blinds all the way up and moved our desks over to the windows so we could see better. This was an unexpected event, but it turned out to be rather fun and was a nice break to our routine. (And the children cooperated very well!)

Recently I complimented my class for not groaning about Heggerty. Jonathan said, �I still don�t like it, but I don�t say anything about it now.� I had talked to them about not complaining and having a good attitude. I am trying to add some interesting things to the Heggerty lesson, by using finger puppets one day, doing Heggerty with stuffed animals, and using different voices and actions. I hope this will help to motivate Jonathan, too.

Here are some ideas for a change of pace and pulling us out of the ruts.

I set the timer and when it rings we stop whatever we�re doing and I read or tell a story. I do this throughout the day.

I might set the timer and whenever it rings we pause and have a joke break. It is also fun to do something on the hour or half-hour throughout the day, and this is also good practice in telling time. So whenever it is 9:00, 10:00, etc., or 8:30, 9:30, 10:30 we pause and do some exercises, have a story, or tell a joke.

We could go outside and pick up trash. This gives us all some fresh air and it feels good to get outside and do something helpful.

Creating something is a good change of pace. Let the class do an open-ended art project, or make cards, or just create something out of the various supplies I put out. Or we could all do an extra and unexpected art project.

Let the students put their desks where they want for the day, or afternoon. (Guidelines: I have to be able to get to my desk; we must be able to get to the bathrooms; no one may be left out.)

Allow the students to sit at a different side of their desks.

We have weekly reading logs when the students are to read for so many minutes a certain number of days in the week. Last week I changed that. We did a Reading Bingo instead of the reading log, for something different.

Some of these activities could be a surprise, which is fun, and some could be announced ahead so the students have the fun of anticipation.

I have a big clapper (hands that bang together when it is moved) and when I find someone who cheers or has a positive comment, I give him the clappers and let him lead us in a cheer for math or whatever the subject is. This is motivating to first-graders and after that we hear many more positive comments!

*Heggerty is a phonemic and phonological awareness curriculum, which is to be done daily for about 10 minutes a day.

Five Helpful Practices for English Class

Photo by Katerina Holmes from Pexels

Here are a few suggestions that I have found to be very helpful when teaching English classes. Too often, some of these concepts are confusing to students, and they fail to grasp onto them, causing them to dislike the subject. I have found that consistently repeating these five practices greatly increased my students’ understanding and enjoyment of the class.

1. Always give the same example when learning a concept so that it will stick in the students’ minds better.

- Examples – Direct objects: The hen laid an egg.

- Indirect objects: David Brainerd gave the Indians Bibles.

- Appositives: Fred, my student, got an A on the test.

- Appositive adjectives: Fred, diligent and hard-working, makes good grades.

2. When working on diagramming sentences, after using some of the examples in the textbook, diagram a few sentences about your students and things that happened at school. They usually love this.

3. Make writing enjoyable. If students write a few sentences a day and enjoy it, the harder and more difficult assignments suddenly become much less of a chore. Using journals daily is a great practice for this.

4.Tackle larger assignments like research papers in smaller chunks. Make each step due fairly soon, give a grade on each step, and keep your students accountable. Dragging it out for weeks feeds procrastination, apathy, and is a breeding ground for students hating writing. It is much more palatable for them to tackle it and write while they have the thoughts and ideas in their brains. In a week, they will have forgotten much of it. I often will make something due every day for two weeks during research paper season, and we will often spend twenty minutes of class doing it. I give them good examples (often from former students’ writing) and cheer them on. They work and write and turn in some good stuff.

5. Read quality literature (including poetry) aloud each day. They need to hear it, and the more they get used to it, the more they will appreciate it. Use voice inflections and be a little dramatic when the piece calls for it – (“The Raven,” anyone?) I once had a class that was really struggling with literature. I got another student to read one of the plays in the literature book aloud with me. We were all laughing so hard (it was a comedy) that I had tears running down my cheeks. They began to enjoy literature much more after that.

Teaching Empathy

Shouts of hilarity rang across the back yard of my cousins’ farm in Indiana. We were playing hide and seek on a Saturday afternoon. Uncle Tim, who was younger than the oldest four cousins, had once again attached himself to someone and squeezed into what they had thought was a great hiding place until a second person tried to fit. Always he chuckled loudly which gave away the site, and usually he stuck out somewhere, as easy to spot as if he were waving a flag. It was something we all regarded fondly as part of playing with Uncle Tim. He had suffered brain damage at birth, and we were used to his quirks, used to interpreting what he was trying to say, used to helping him with his buttons or his shoes. When he was difficult, our parents coached us in appropriate ways to handle the situation.

We didn’t know that our hearts were being enlarged or that we were learning secrets about relating to mentally handicapped people. It was just a part of life, which is probably the most effective way to learn anything.

When he was a teen, Uncle Tim lived with our family for a while. I was shocked when children who didn’t know him would tease or mock him. Didn’t they know he had feelings too? Our schoolteacher was open to him attending classes. He said it would be a good experience for the other students. With wise supervision and kindness, Tim soon blended into the classroom, sitting in his corner with coloring pages and workbooks every day. Older students would finish their algebra and help him with his numbers flashcards, and he would struggle with the same ones every time. Sometimes he concentrated so hard that he would drool and have to be reminded to get a tissue to wipe it. He made no noticeable academic progress, but Tim became one of the crowd, limping along at recess, chortling his delight when he tagged someone. The students from those days have not forgotten him and he has not forgotten them. He could only read a few words and count to fourteen, but he taught us all lessons in empathy.

Practicing Empathy in Real Life

There is so much wonderful diversity in our world, yet we tend to sort ourselves into safe categories of sameness. We are not born instinctively knowing how to relate to those who are different from us. We may have harmful prejudices that have no basis except that we do not understand the other person. Maybe they speak with a foreign accent, maybe they carry a cardboard sign begging for money, maybe they are voiceless in a wheelchair. As we grow older, we learn social norms for how not to act, but just avoiding staring is not empathy. We need to open our hearts to learn about their lives, how they like to be treated. We need to feel deep in our souls that they are worthy of dignity and love, just as we are.

Children can be cruel to those who don’t fit their societal mold, but they also have great capacity for kindness and understanding. As teachers and parents, we can introduce our children to situations and people that they have not encountered in their lives.

There are endless opportunities to learn to care about others and serve them. A few come to mind:

- Care about the lonely and marginalized. Visit the elderly, hear their stories, and learn about life a few generations past.

- Care about the homeless. Volunteer in soup kitchens or food drives.

- Care for the disabled. Find an organization such as Love INC that matches your skills to needs around you.

- Care about the destitute. Make Christmas shoeboxes instead of doing gift exchanges. Let giving be more important than receiving.

- Care about orphans. Sponsor someone and pray for them regularly.

- Care for refugees. Gather coats and extra winter clothing for distribution.

Learning Empathy From Books

Sometimes it isn’t possible to physically meet the people we want to understand. This is where we can introduce children to other people in other worlds through stories.

When my fourth-grade teacher read the book Star of Light by Patricia St. John, I imagined for the first time how it might feel to be a little beggar on the street. It was not a sight I ever saw in our small town, but there were times when a man stood at the stoplight with a sign that asked for money to feed his family. I would wonder about his story, and I couldn’t just dismiss him as a loser. He must have feelings too.

To help our children visualize other worlds, I invested in some photo essay collections. One is a beautiful book titled Where Children Sleep by James Mollison. Peter Menzel has published numerous collections of photos. We enjoyed What the World Eats and Material World. It has been interesting to hear our children commenting about how some of the happiest looking faces are the ones with the fewest possessions. The more they are exposed to other worlds, the more their capacity for empathy grows.

Why Empathy Matters

Micah 6:8 gives us the heart of empathy. “He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?”

We are concerned about sheltering our children from the evils in the world, as we should be. However, if we want them to live compassionate lives, we have to let them see some of the brokenness in the world. Empathy is an emotional skill; it develops through learning to care about other people. When we give our children the chance to know someone in a different world from their own, they learn and grow.

English Class (Or Any Class) Can Be Fun!

It happens all too often. People ask me what I do, and I say, “I’m a high school and college English teacher!” I’m usually met with the same response: eye-rolls and comments about how “I hated writing when I was in school” or “I don’t like to read.”

But English class can be fun. And so can any class, if it is approached with the right attitude and some creative planning. Granted, the students’ attitudes and motivation make a significant contribution to their enjoyment of a class. But by using some of the following methods, a teacher can make the class fun for every student.

A fun class has a teacher who models enthusiasm for the subject. I have found that when I’m bored with something, my students are usually bored too. But when I show passion for the story we’re reading or the grammar lesson, that enthusiasm is usually infectious. My students typically rate Shakespeare plays as their favorite part of literature classes, I believe reflecting my personal interest and enjoyment of teaching Hamlet and Macbeth.A fun class mixes hands-on activities with lecturing, even on the high school level. My eighth-graders who are an especially tactile group this year, complete interactive grammar notebooks and spelling activities (see attachment below) regularly; this has greatly enhanced their learning. Paper flashcards still provide a good way to learn vocabulary words, and the cards can double for use in games like memory or concentration.A fun class engages students with different learning styles. Many teachers, especially in higher grades, center their lessons around lecture and maybe slides, which really only grab those who learn orally. But including some movement or audio can engage other types of learners also. Instead of just reading a Shakespeare play, students can listen to an audio version while following along with the text. A favorite student activity when discussing a short story—even with my college students—is to tape large pieces of paper onto the walls with a quotation or question from the story written on each paper. Each student moves around the room and writes thoughts and responses on a certain amount of papers. Kinesthetic games such as four corners (see directions below) allow movement for that student who just can’t sit still.A fun class allows the students to share what they are learning. High schoolers can re-write a literature story as an illustrated children’s book to read to younger grades. They can share memorized poems in chapel or other group settings. Student-made posters that illustrate story elements can be displayed in hallways.English class—and math class and science class and social studies class—can have all sorts of enjoyable activities. So learn and have fun at the same time!

Resources:

Four Corners

- Place the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 on each corner of your classroom.

- One student closes his eyes and counts to 20 while the other students quietly go to different corners in the room. As long as possible, there need to be at least two students per corner. Each student has to move on every turn.

- Without opening his eyes, the counter says 1, 2, 3, or 4.

- The teacher asks a question. Whoever is in the named corner will answer the question. They may confer on the answer.

- If the students in the named corner get the answer correct, they stay in the game and a new round begins. If the students miss the question, they return to their seats. A new round begins with the remaining students.

- When only three students are left, use only three corners.

- The last two students remaining are the winners.

I Can't Do This

I'm finished with class. The students are starting to work on their problems.

Billy again. You know Billy. Billy says, "I don't know how to do this problem."

It's today's problem. There are examples on the board. Billy doesn't know how to do the problem.

So I try to do the right thing. I say, "OK, let's look at this. Let's see how this problem is connected to things you already know how to do. It's just an extension of things you already know."

So I'm trying to do this. And finally, in exasperation, Billy says, "Can you just tell me how to do it? I'm never going to understand why."

If you've taught for any length of time, you've had a Billy in your class. In my experience, the Billies of my classroom have been saying things beyond "I can't do this" in three ways. So the first thing that Billy might be saying is this.

It's a belief about people in general and a belief about himself. The belief is this. Some people can. I cannot. Notice Billy does not say, "This is impossible." Billy says, "This is impossible for me."

Tenacity

I would suggest a character trait we might develop in Billy is the trait of tenacity. Tenacity is the ability to keep working. Even when it's hard, even when it's not fun, even when you're experiencing failure. Tenacity is the ability to keep going beyond the frustration.

Thomas Edison is an illustration of a tenacious person. His famous quote is that "Genius is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration." I will point out that everything truly valuable in life is worth working for. In fact, everything truly valuable in life, you have to work for. I think it was Thomas Paine who said that "What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly. Heaven knows how to put a proper price on its goods."

When we worked hard for something, the reward for that work is often, is always, I would say, deeper and longer lasting than the cheap participation trophies that we often give or get for less than stellar effort. Tenacity is a habit of mind. It's a habit of life that allows us to keep going when it's hard.

Growth Mindset

Carol Dweck is a researcher who has made the case that our brains are malleable. She calls them plastic. They can change in their function. So we often think of our students and we think of ourselves as having a certain level of capacity. And then what we need to do as teachers is we need to get our students up close to their capacity. That's a very common approach.

And that's what Carol Dwett calls a fixed mindset that the student has a limited capacity. Whatever that capacity is, it may be higher, it may be lower, but there is a set capacity. Now let's just pause for a moment to recognize. We know that that capacity can be lowered if students experience abuse. The capacity to learn is reduced if they experience loss or some other kind of stress, the capacity to learn is reduced. Right? So we all know that it can go down.

What Carol Dweck says is it can go up as well, depending on your mindset. So she calls this a "fixed mindset" where you believe that every student has some capacity individually and that that's fixed.

Carol Dweck argues for what's called a "growth mindset," in which not only are we trying to grow our students in their achievement, we're also trying to grow their capacity.

I find it helpful to think about responding to Billy in this way. When Billy says, "I cannot" I say, "You cannot yet."

One of the things that Carol Dweck highlights as a teacher feedback mechanism that is correlated with a growth mindset in students is that we praise effort, not ability.

So if Billy has been going through school being told, "You're good at things. You have capacity." Then when Billy comes up against something that's hard, guess what he's going to believe about himself. "Teacher doesn't actually know I'm a fake. I've faked it up till now. Teacher doesn't know that I'm actually not that good. I've been faking it." So Billy starts to believe of himself that he can't do it.

If instead of saying, "You're good at this, Billy, you're good at math." Instead you say, "Billy, I really like how hard you're working in math, and that's paying off for you." Then when Billy comes up against something hard, it's not an obstacle to be avoided. It's an obstacle to be overcome.

The second thing that Billy may have is what Fred Jones calls "learned helplessness" or a teacher dependence and unhealthy teacher dependence. Certain students, if you would let them, they would have you beside their desk the entire day looking over their shoulder, watching everything they do. Right? That's something that they need to be weaned off of children who have had a hard time with school have had more messages of failure than other students.

So here's what can happen. Billy calls me over to his desk. I look at his math work, and I say, "OK, you did steps one, two, and three right, but here's where you made a mistake." Notice that little word "but." That undoes everything that I have just said positive about what Billy did. We're focusing on what Billy did wrong. For some students, that's invisible. For Billy, that's not. Because, for Billy, he has had these messages of failure, these negative messages, probably quite a lot.

So I need to be careful in my feedback to a student who wants me by their side every step of the way.

Praise, Prompt, and Leave

An approach that I've tried, and it works�it's called "praise, prompt, and leave." You focus on what the student did right.

"Look, you did the first three steps correctly," and then you don't use the word �but� or anything like that. Instead, you say, "The next thing to do is," and only give them the next thing.

So here's the temptation. There's eleven steps along the way. They've done the first four. We look at step five, and we say, "OK, here's the next thing to do. And then I know I'm going to have to come back and tell him step six. So I may as well tell him right now. And step seven, and eight, and nine, and now he's in cognitive overload.

Praise, prompt, and leave says, �No, just do the very next thing." And if Billy has to call you back over for step six, praise, prompt, and leave again.

Learning Disabilities

I'm going to do a quick aside here, though, and point out too that not all of our students just need to work harder. There are students who have learning disabilities that actually do make things much more challenging for them than they are, even for us. If you talk to somebody who, for example, has dyslexia and whose teachers did not understand them and who got spankings for not working hard enough, it'll kind of scare you. It isn't always the case that students need to work harder. However, even students with learning disabilities can grow their abilities with tenacity.

Don�t Apologize for Hard Work

I have stopped apologizing to my students for asking them to do hard things. I've stopped apologizing for hard work. In fact, in their senior year, students get to decide what math course they do, and I always try to get at least some of them to take calculus. And they ask, "Why should I take calculus?" And I say, "Because it's hard. Because you're going to work your tail off and it's going to be great."

We do need to have meaningful practice of this habit of tenacity in our classrooms, and I don't know what that looks like in every grade level. But if we can have meaningful practice of tenacious habits, our students will grow beyond their current limitations.

The Fear of Failure

There's a third possible reason why the student says, I can't do this, and that is the student may be afraid that they will fail at this task. "I can't do this" may mean rather than "I can't do this at all" "I can't do this to the standard that I hold for myself." Billy may be afraid of failure.

A fear of failure can debilitate even the most gifted of students. And for a student like that, it's not actually tenacity that they need. I've had students top of the class. They study for 3 hours for a test. They could ace the test without studying, but they still study for 3 hours. Why? Because they don't want to fail.

I had a student one time who got a 99% on a test and came back to me after the test. After I gave the test back, she came back to me. She said, "Mr. Kuhns, you didn't add up the extra credit, right? I actually had 100%." And she was right. I had missed an extra credit question, and she did have 100%. Straight 100s all the way through.

And I told her later, I said, "You know, I was disappointed. I wanted you to get a 99%."

She said, "What? Why?"

She said... I told her, "Because I wanted you to see that getting a 99% is not the end of the world."

Most of us can only dream of that kind of even like having that a possibility. Right? But she thanked me for that years later. She said, "You know, that was a turning point for me because I thought that my teachers wanted me to be perfect, and I realized they didn't."

Carefulness Instead of Perfectionism

If we're holding for our students this standard of "You always have to do your very best," guess what? We don't live up to that standard ourselves. I would say here that a fear of failure comes out of a misapplication of another habit, another virtue, intellectual virtue, and that is the virtue of carefulness.

We believe in carefulness. We believe in students doing well, being careful in their work, being neat and thorough and doing all the steps, all these things. That's good.

Carefulness is that consistent habit of being patient and diligent in the pursuit of truth. It is not excessive fastidiousness. So carefulness misapplied takes us to perfectionism.

So the difference between a perfectionist and a craftsman. I actually put this quote on my desk as a reminder to myself, because I can be a bit of a perfectionist. The difference between a perfectionist and a craftsman. Both the perfectionist and the craftsman can see the flaws in their work, but the perfectionist is debilitated by it. The craftsman can keep going.

We want our students to become craftspeople in their work. We don't want them to become perfectionists.

Now our students do rise and shrink according to our expectations for them. But one of the things that I want to do in my classroom is I want to create an atmosphere in which it's okay to fail. But it's not okay just to fail. Here's what I mean. Failure is a key to success if and only if you're learning from your mistakes. Every time you fail, you need to learn from that mistake. But if I can create a culture in my classroom where it's safe, where students can fail.

The thing that makes me most angry at a student is if they're mocking another one for failing. You do not do that in my classroom. If the classroom isn't safe for somebody to fail to ask the dumb question, if they're not safe to do that, they're going to be afraid. And that fear. Remember what I said about our ability to learn? Fear reduces that as well.

Conclusion

Second Corinthians 4:7. He says, "We have this treasure in jars of clay to show that the surpassing power belongs to God and not to us." It's an important aside that I'm just going to let go. "We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed, perplexed but not driven to despair, persecuted but not forsaken, struck down but not destroyed, always carrying in the body the death of Jesus so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies. For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus sake so that the life of Jesus may also be manifest in our mortal flesh. So death is at work in us, but life in you."

Hopping down to verse 16, he says, "So we do not lose heart. Though our outer self is wasting away, our outer self is suffering, our inner self is being renewed day by day. For this light momentary affliction is preparing us for an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison as we look not to the things that are seen, but to the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal."

Classrooms filled with tenacious teachers and students are classrooms where learning can flourish if we see difficulty as an opportunity to grow rather than as a thing to be avoided. Both student and teacher can lean in when the going gets tough. When that happens, I propose we will produce adults who are better equipped to serve Christ in his Kingdom.

Creating Enthusiasm for Writing

“Is today journaling?” eagerly asks my little student, a non-native English speaker.

“Yes!” Their cheers greet the announcement of journal class.

I’m greeted by students in the morning. “I know what I’m going to journal about. Can I whisper it in your ear?”

Do I simply have a class of students who all enjoy writing; or is an enthusiasm for writing something that can be cultivated? I firmly believe that all students can learn to enjoy putting thoughts on paper, even though they are not the compulsive writers that their fellow classmate may be. And, the time to begin is during the first days of school.

Have a routine time for writing and require everyone to participate during this time

You can have a five-minute journaling slot every day. You can have a thirty-to-forty-minute slot twice a week. A key to writing without groans is for it to become ordinary and routine. Students learn to anticipate the class and mentally prepare themselves for it.

Make the writing time a priority. A co-teacher recently shared that her journaling time has not been as successful this year because she did not set a certain time for the students to actually write. It became one more thing they should do when they finished their required subjects and less students actually participated in the exercise.

Writing is somewhat like a physical exercise routine. If the habit is maintained, interest and participation will remain high. If one slacks off the routine and skips some days, it is easy to become lazy. Writing takes discipline and effort. It is an exercise of the mind.

Keep writing pertinent

Most of us have students in our classroom who, if allowed, would tell stories all class period. Younger children, especially, love to tell others about themselves. Journaling is a time they can share these stories.

Older students enjoy creative prompts or creative ways to write about the ordinary. There are many resources available to help spark creativity, including resources on The Dock.*

Give students a reason to write

Younger students enjoy sharing their stories and pictures with each other during a journaling share time. The shyer student may need encouragement but I seldom let a student skip sharing with their classmates. I have yet to have a child that has not overcome their reluctance to stand in front of their classmates and share their story. When this becomes the normal and expected experience it is no different than any other class process. As I comment on the stories they share, it is a way to give them recognition and affirmation.

Older students may be more reluctant to read their writings in front of classmates but at least some of their writings should be for an audience, even if it’s just a class booklet of their favorite pieces or a letter they send to their elderly grandparent.

Encourage creativity more than polished and proper papers

There is a time and place for critiquing student writing. However, allowing students to put their thoughts on paper without worrying about proper spelling, grammar, and punctuation can be freeing to the child who struggles in these areas but has creative things to say. Students should be required to read back over what they’ve written to make sure it says what they wanted it to say and to catch the obvious errors. They should not need to feel the need to edit and rewrite most pieces.

Keep the proofread and edited pieces for those in the Language Arts program or those pieces that need polishing for printing purposes. (This is an important skill to be learned—just not at the expense of creative writing experiences.)

Provide help as needed

Writing blocks often fall in two categories: lack of subject material, or lack of ability to produce what is envisioned. You as the teacher can provide aid for the student in both of these areas.

In introducing a topic or prompt, have a brainstorming session to warm up. Help the students get the creative juices flowing. If you as a teacher have an example to show them, it will provide a model for the less creative.

For classes where students choose their own topics, have a few suggestions available.

In my first-grade journal classes, telling the story is as much about drawing pictures as it is putting words on the page. Some students are uncomfortable with their drawing skills; however, with encouragement and no criticism most of them are willing to put something on their pages.

Spelling issues can also hinder some students. Along with allowing phonetically spelled words, each of my first graders has an index card of words that they ask me to spell for them. They keep these cards and can use the lists the next time they need the same word.

Provide an introduction to each class

Take a few minutes at the start of each journal period to pull students into the class. My journaling periods usually start with a short well-written, age-appropriate story. We enjoy the words and pictures together before they launch into their own compositions.

An introduction to the prompt and a brainstorming session can get the creative juices flowing. Depending on the type of writing, a discussion of various samples may be appropriate.

Set the students up for success

Writing is personal. Each person has their own style and unique ability. Encourage the best in each student but allow them their own expression. The key ways that help students be successful with writing is to provide a writing routine, focus more on expression than structure, and make it purposeful.

The groans may not disappear right away, but keep at it. Eventually the students will realize that writing is not such hard work after all!

Suggested resources:

Lower Elementary Creative Writing Lesson PlansTen Ways to Promote Creative WritingA Dozen Writing LeadsShort, Fun, and Often: Using Journals to Spark Creative Composition

Early Intervention: Before School Age

This is the time of the year when I start screening students entering the classroom in the fall. For two private Anabaptist schools in the area, I test any new students wanting to apply to kindergarten. If they have chosen to do kindergarten at home, I test the student going into first grade. Or if the kindergarten teacher of the school has a concern about one of her students, I will retest the child before entering first grade. My purpose in administrating the Gesell Developmental Test is to fulfill the following three questions:

- Is this child ready to enroll into kindergarten/first grade?

- Would this child benefit from an additional year at home before enrolling in a traditional classroom environment?

- Does this child need extra learning support coming into the school? And if so, is the school able to provide it or is there additional learning support that they should be receiving that the school is unable to provide?

Identify the Children Who Are Not Meeting Typical Milestones in Development

After screening the students, most students will fall into the first category. Often, there are several who fall into the second category and would really benefit having an additional year of brain development before entering traditional schooling. (Read Outliers: The Story of Success if you want some type of idea of what an extra year or half year of development can do to a child.) It is rare that I will find a child who falls into the latter category�needing extra learning support from the onset. It is even more rare that they will need learning support that the school is unable to provide. But in my seven years of testing students, there have been students who not only need learning support from the moment they enter the classroom but they also would have benefitted from receiving learning support earlier and have not been receiving it.

Those are the students whose condition breaks my heart. When a child comes to kindergarten or first grade with a large gap in their development or abilities, they have a long, grueling climb ahead. The learning process happening in the classroom that is so enjoyable to the rest of their peers is daunting and frustrating for them. It is those students who could have benefited from Early Intervention, and I wonder why we are not allowing our students to benefit from this one-on-one service and learning opportunity.

In too many cases, we are waiting until our children are already entering the traditional classroom before we are addressing speech difficulties, ADHD tendencies, dyslexia, symptoms of autism, and other learning difficulties. That is not necessary! Early Intervention is designed to help children narrow that developmental gap BEFORE they reach the classroom. For example, if you have a child with a speech impediment or delay, they could be receiving free high-quality speech therapy in their own homes rather than having to wait to be pulled out of the classroom or taken after school hours for speech therapy. Why not work on the gap in development before school age so that it does not 1) cause embarrassment to confusion for the student 2) distract or take away from classroom time 3) negatively affect learning literacy and communication skills.

Early Intervention: What Is It?

Each state within the United States of America provides Early Intervention services for children between the ages of birth to five years old who are experiencing delays in development. They provide coaching support and professionals services for families who are interested. According to Pennsylvania�s Early Intervention website, they provide services for the following:

- Physical development, including vision and hearing

- Cognitive development

- Communication development

- Social or emotional development

- Adaptive development

In most cases, the support and services are done within the home. After the initial evaluation to see if the child qualifies for services, the therapist or teacher will come into the home on a weekly basis for about an hour to teach within a play-bases setting. It is of no cost to the family, and the family has the right to request or refuse services at any time.

Early Intervention: Debunking the Skeptics

�If we know there is something we could do to give greater academic advantage to our child, why would we not use the services? I believe that about 25% of the students whom I test on a yearly basis would have needs or gaps in development that would qualify for receiving Early Intervention services. And yet, I rarely meet a family who has pursued it or received any assistance for their child. Why is that?- Ignorance: I believe that most of our parents do not know about the services. Because we have had so few people over the year who have used it, receiving the services is not �normalized.� A speech therapist who actually comes into the home for free and works with your child and from whom you can get tips to work on helping your child�s incorrect speech patterns? Most families have no idea that the service is available.

- Government Program: �It is a free handout from the government that we should not be receiving.� To that I ask, are you not paying your taxes? As homeowners, we pay a mandated school tax every year. You are paying for those services whether or not you are using them. You enjoy driving on roads that are maintained and cared for by the local municipality, why not also make good use of your tax dollars by giving your child assistance that could help them to have a better school experience?