All Content

Book Report Outline & Author Posters

A book report outline and a collection of author posters featuring Hesba Stretton, Sydney Taylor, Dr. Paul White, Meindert de Jong, and Johanna Spyri.

From the contributor: "I put up one author’s poster per bulletin board display, and then I put books written by that author around the poster. The students each chose a book to read, then they used this outline to write a book report. They drew sketches of the story characters and events in the frames on the righthand side of the page. I then hung their reports beside the books they had read."

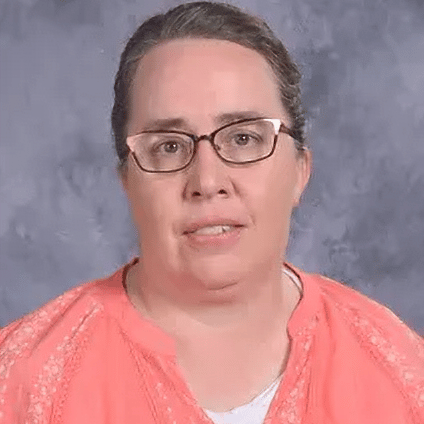

Habits to Sustain Long-term Career Teaching

This year marks my fourteenth year teaching full-time in a parochial school classroom, and it hasn’t always been easy. But, because I love teaching and spending my time imparting knowledge to and guiding little humans, it has been well worth it. Here are a few habits that have helped our family stay in the teaching profession. Because I feel it’s an extremely worthwhile way to spend one’s time, I’ll share them with you here with the hopes that you, too, will consider teaching as a long-term commitment (if you haven’t already.)

- Go all-out. If we approach teaching as a chore or a short-term commitment and watch the clock throughout the day (and the calendar throughout the weeks and months), our focus becomes finishing the day, the week, or the month. But, if we practice carpe diem, (“seize the day”) our approach will be much different. Today, for instance, I regretted that I had forgotten an egg and vinegar for a science experiment. I wish we would have had ten more minutes to get every single math problem fixed up for a 100%, another fifteen minutes of music class, five more minutes on the tennis court, and another twenty minutes of art class. My students and I were having such a great time that by the end of the day the clock was already three minutes past dismissal time when I happened to look up and realize it. Go all-out! Dream of what you’d like your classroom to be like, and do what you can to make it happen. (And yes, some days I do glance at the clock.)

- Enjoy those holiday breaks and summers! Because I do go all-out during the school year, I cherish my days off. I need them to relax and recharge. That’s another great bonus of teaching: we get nice long holiday breaks and fabulous summers completely off.

- Find your stress points and reduce them. This year one of my stress points was packing up everything the last day of the week and putting it all away into a small closet. (We are currently renting a church’s fellowship hall.)The job was taking me a couple of hours and was definitely a stress point. After a few weeks of this, I got my students to help me in an orderly, assigned way, and it cut my time considerably. I also had too many papers to grade and no time to grade them except after school. I asked my helper to focus on grading papers, especially the math ones, as soon as she was done teaching her lessons. Another stress point gone! Work on these until you have minimized the most stressful spots, and keep doing it as the year goes on.

- Cut your budget wherever you can. I feel that it is well worth the trade-off in pay to do something that I truly love and enjoy doing, and my teacher husband feels the same way. While we wouldn’t call these “sacrifices,” some people looking on might. We have shared one car for most of our teaching years, and it is thirteen years old. We don’t take expensive vacations or eat out a lot. We have a fairly modest home that we fixed up ourselves, and we love it. We have been able to save money and contribute to a retirement account. We don’t feel deprived. Rather, we feel thankful that we have been able to spend our time doing something that we truly enjoy and have been able to provide well for our family while doing it. That’s what we would consider success–happiness and family together time–not fancy cars, expensive vacations, and other stuff that we really don’t need.

- Get a low-maintenance side hustle. We have chosen to teach a few weekends out of the year and a few weeks in the summer. We also teach private music lessons and do consulting. These are things that we love to do and don't stress us out. We still have plenty of time to relax. We have teacher friends who have chicken barns, do private tutoring, carpentry, make donuts, or have rental houses.

- Get your family, roommates, and friends on board. Whoever lives in the same house as you do, or whomever you choose to spend time with, should care enough about you personally to encourage and help you in your teaching endeavors. I’ve heard of roommates who made meals, family members who ran errands, and parents of teachers who substituted for their teacher-children. I’ve had students mow my lawn and feed my cats when we were out of town. Graciously let your needs be known, but don’t be needy.

- Find a teacher-friend or two to be confidants and/or mentors. It’s great to bounce your thoughts and ideas off someone else, or to call them for some advice or encouragement when you need it. Often you’ll find that you probably do the same for them. Look for someone with experience who inspires you. Experience is gold; inspiration is silver.

- Plan ahead. This is probably the single most important aspect that has helped me as a teacher and as a mother. After school, I get dinner ready and prepare the next night’s dinner. I also have a good calendar system with personal, family, church, and school events all on it. This not only helps me to plan ahead, but to look ahead daily, see what’s coming up, and make sure that I’m well prepared for it. It has saved me much worry and time.

Teaching is a fabulous profession! We are investing our time and energy into helping other people. With just a bit of vision, planning, and commitment, it is easily sustainable long-term.

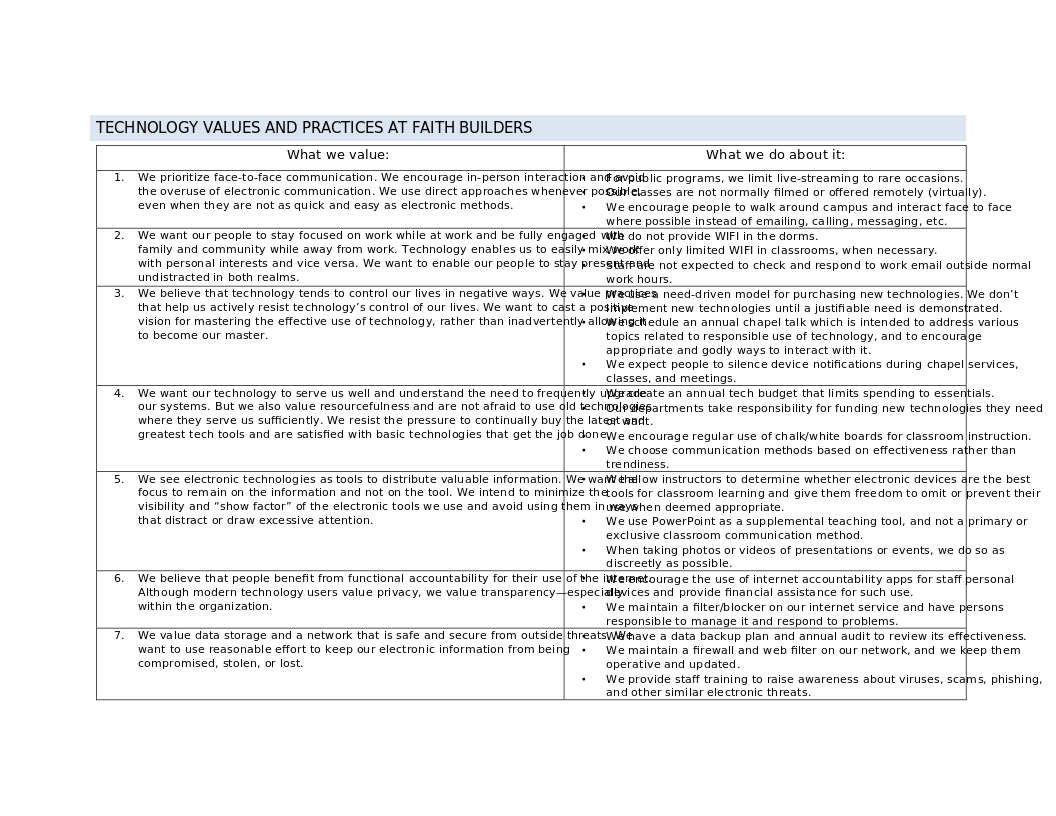

Values and Practices for the Use of Technology

Technology accelerates communication. But what does this do for your school?

Faith Builders developed a list of values for the use of technology along with accompanying action items. You may find a list like this inspiring as you develop your own practices.

Relational Practices for Task-Oriented Teachers

I find personality tests intriguing. Enneagram, Myers-Briggs, DISC, and other frameworks for explaining the way human beings operate have helped me to understand myself and other people in new ways. I had studied many of these in various seasons of my life, but one aspect of personality that I have found particularly helpful has only come to my attention in recent years: the difference between people-oriented and task-oriented individuals.

People-oriented people are very relational. They always have time to sit down and talk; the work can wait. They love people by taking time for them, talking with them, and offering a listening ear. Task-oriented people, on the other hand, are the diligent workers. They get the job done. They love people by doing things for them and by producing quality workmanship.

While both sides have strengths, the weakness of either extreme is obvious. Task-oriented people tend to emphasize work at the expense of relationships. People-oriented people fall into the ditch on the other side. They are so busy interacting with people that they neglect necessary work. Recognizing our own natural tendency to lean toward one side or the other can help us to work on becoming more balanced. Perhaps even more than some other professions, school teaching requires a delicate balance of both relational skills and efficient work skills.

As a very task-oriented person, I write this especially for other task-oriented teachers, because we need to be more intentional in taking time for relationships with our students. We are good at accomplishing tasks. We plan and execute great lessons and projects, we get those stacks of papers graded, and we sweep that messy floor. But sometimes in our zeal to do all the things and to give our students a quality education, we miss their hearts.

While “trying to be more relational” can seem like a nebulous goal, it is possible to take small practical steps in that direction. Here are a few things I have done:

Greet your students at the door in the morning. This is something I wish I would have done earlier in my teaching career. It is meaningful to look each child in the eye and to greet them by name as they enter the classroom. They have your full attention. You are not at your desk doing last-minute grading or lesson preparation. Last year I received a note from one of my students from the previous year, and among other things she wrote, “I liked how you smiled and said ‘Good morning’ to me every day when I walked in the door.” This child is extremely relational, and it warmed my heart to know that I had connected with her in a way that she remembered and was able to articulate so clearly.Allow class time for students to tell their stories. It can feel like a waste of time to allow precious minutes for students to tell about their new puppies, their trip to visit cousins, or their latest inventions. But this can be a great time of connection with students. I’m learning to quiet the little voice in my head that says, “But we have so much to do!” and to let my students talk about the things that are important to them. We need to have limits for this, of course. But especially after a weekend or other break from school, I take five to ten minutes in the morning just to let students talk about the things they did or whatever is on their minds.Write notes to your students. This is a wonderful relational tool for us task-oriented people, because it is a job we can cross off a list. At the same time, it is a meaningful way to connect with students. I keep a handy stash of little cards in my desk for this purpose, and it takes only a minute or two to write a short note praising a student for something positive I noticed, or even just saying, “I love having you in my class. Have a great day!” Recently the mother of one of my students told me how much it meant to her daughter when she got a note from me. I was reminded that little things like this can have a big impact.Resist the urge to be constantly at work. At our school, we have an unstructured morning break and lunch break. Students are free to play in the gym or on the playground when they finish eating. Not all of us teachers need to be out there supervising, and technically I could use this time to gather supplies from the art closet, run to the office to make copies, review the next class period’s lesson plans, etc. To be honest, sometimes I do those things. But I am also learning to spend more time with my students and to refocus my brain from its natural task-oriented mindset.Be interested in the things that interest your students. I have no interest at all in football or hunting, but my students don’t have to know that. I can still smile and nod at their stories, ask questions, and encourage them to pursue their interests. I can learn the names of their pets and ask about them sometimes.By God’s grace, we can continually learn new habits of connection, even if we are not naturally people-oriented.

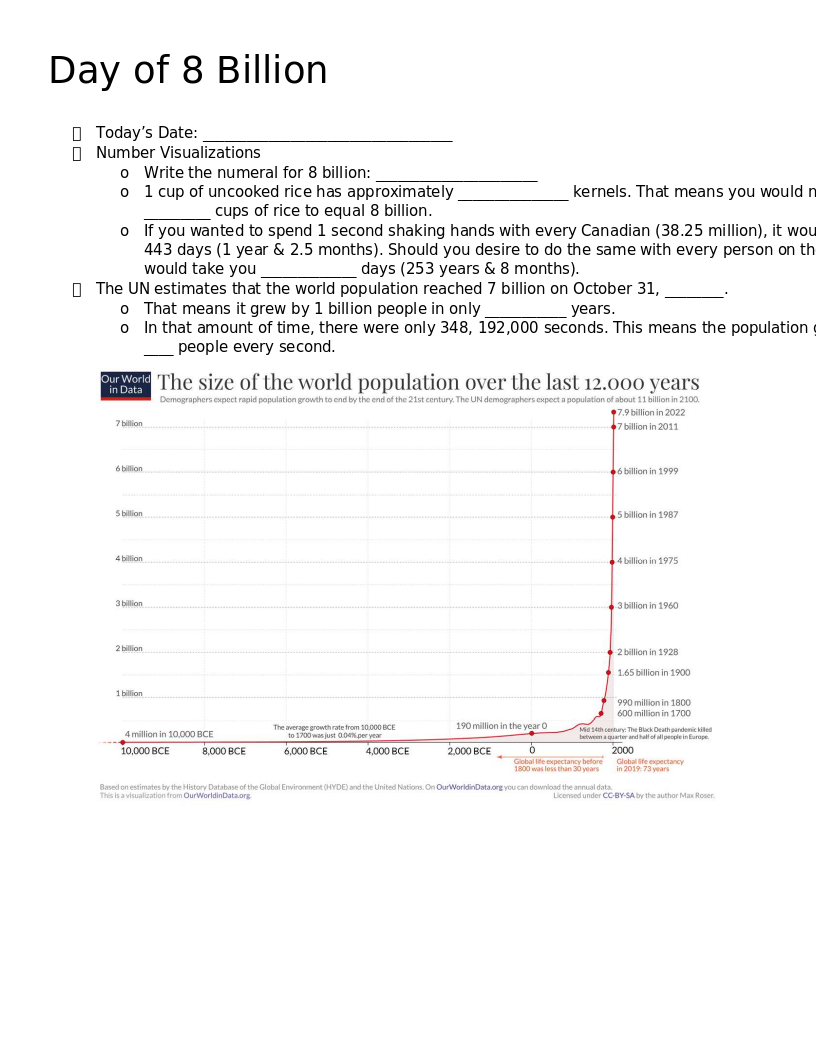

Day of 8 Billion

According to the UN, the global population reached a milestone 8 billion on November 15, 2022. This lesson plan and worksheet discusses world population and helps students visualize the magnitude of the number. The student worksheet includes major points, graphs, and calculation problems. The teacher guide includes answers, additional comments, graphs, and weblinks for further illustration and discussion.

Do the Write Thing, Part I: Why Writing Matters

The adage says, “The pen is mightier than the sword.” As conservative Anabaptists, we have traditionally avoided using the sword. But unfortunately, we have often avoided using the pen as well.

The following observations are very likely not a true representation of all Anabaptist schools and painting in broad strokes is sure to lead to unfair stereotypes at times. However, it seems to me that in many schools, writing is limited either to very functional uses, or to a brief, extra subject called Creative Writing that we squeeze into our schedules once a week. We give only a fraction of time to learning to write creative, original work compared to the time we spend on things like math, science, history, or the mechanics of grammar.

But these priorities of time matter, because where we choose to spend our time has an impact. When we spend so little time honing the craft of writing, we are not raising a generation of children who have the skills to impact their world by invigorating and inspiring their readers.

This is a shame, because as Christian schools, we should care about writing.

A Philosophy of Writing

“In the beginning, God created.” God is a creator. We know this from the first five words of the Bible. And within the first chapter, we are told that we as humans are made in His image. The fact that humans can create is a core aspect of what it means to be image-bearers. And arguably, writing is one of the closest ways we have of creating ex nihilo (out of nothing) as God does.

When we teach children how to write well, we give them a gift. It is the gift of imagination—of allowing their creativity to take flight instead of becoming mired in the world of facts, concrete ideas, and entertainment.

Teaching writing is the gift of articulation—of taking the seeds of thought developing in their minds and letting them come to fruition on paper.

Teaching writing is the gift of self-reflection—of grasping at the vapors of who they truly are inside and bringing them outside to be understood more fully.

Teaching writing is the gift of beauty—of using twenty-six letters to weave tapestries of delight.

When children have been given these gifts of imagination, articulation, self-reflection, and beauty, they have more tools to serve God and build His kingdom. This broken world needs Christian writers to rise up and speak a message of hope. Students from Christian schools ought to be graduating with the tools they need to be able to write well.

Further, communication—and therefore writing—is an act of worship. God is a communicator, and He gives us the ability to communicate with others. In fact, communication is part of the believer’s calling, and it is an essential part of sharing the gospel.

Engaging students in the process of writing is a core part of helping them learn to develop ideas and think well. Therefore, it is not an activity reserved for the few Christians who are “born writers.” When our students are better writers, they will be better communicators, whether written or verbal. Therefore, it is a worthwhile process for all believers and an important skill to teach our children.

Writing enables three important things for our students: processing, persuasion, and pleasure.

Processing

We all have problems. We all struggle with conflicting ideas, looming worries, and niggling doubts. Our students are no different. It’s complicated to be a child. It’s especially complicated to be a teenager.

Writing is a way of processing problems to come to conclusions. It’s a valuable skill our students need in order to make sense of life, both what’s going on around them and what’s going on inside of them.

Another reason writing is important is because writing about their thoughts helps our children learn how to develop their thoughts. This ability to think and think deeply cultivates emotional growth. We don’t just teach to our student’s heads; we teach to their hearts, too. Writing is a way to do that by giving them the ability to reflect on their thoughts and emotions.

Of course, this doesn’t happen easily or all at once. But over time, as they hone their writing skills, children will be able to develop their thoughts in helpful, healthy ways. They will be able to clarify those thoughts and sharpen them towards truth. That is a gift that we should be giving our students.

Processing can be an end in itself, and that is a valid use for writing. But writing can also be the means to persuasion—the ability to articulate truth in a compelling way.

Persuasion

As Christians, we are called to defend and proclaim truth. Part of the Christian school’s role in serving the church is to help shape children who are able to do that.

Writing is a powerful method of communication. It is so important that our children can articulate their beliefs, especially in a world that is continually throwing Christian values away. Equipping them with the skills they need to be able to write well is a vital step in that process.

The first thing writing does is force our students to wrestle with ideas themselves, which strengthens their own beliefs. But it also prepares them to share their beliefs with others. Our world desperately needs skilled writers to speak into the brokenness with a message of hope.

As Anabaptists we have much to offer, but often, we aren't extending hope in quality literature. In order for us as an Anabaptist people to become talented writers who can share life and light through our words, we need to spend significant time building writing skills in our children.

Now, as important as this purposeful writing is, I strongly believe that writing doesn't have to be functional to be valuable. We should also allow students to write just for the pure pleasure of it.

Pleasure

Do you remember what it was like to be a child, and your imagination was so alive it could take you anywhere? Perhaps your bike was a horse that galloped with thundering hooves or a race car that sped around corners with devilish speed. You could be a cowboy, a pioneer, and a major league baseball player all between lunch and supper.

Walt Disney once said, "Every child is born blessed with a vivid imagination. But just as a muscle grows flabby with disuse, so the bright imagination of a child pales in later years if he ceases to exercise it."

This is especially true in an age of technology when all the imagining is being done for children already. For example, it takes much less imagination to watch a movie than it does to read a book. In many homes, hours of screen time inside replaces time in imaginative play outside. It is difficult to objectively compare children today to children twenty years ago, but it seems that students with vibrant imaginations are becoming increasingly rare. The idea that technology may be robbing our children of their imaginations alarms me.

And of course, as teachers, we are considerably limited in how much control we have over our students’ technology usage. However, we can give them opportunities to exercise their imaginations at school. One of the best ways to do that is through writing.

Now, writing is not always fun. But writing should be fun sometimes. Students should have the opportunity to create new worlds that they wish existed, experience the delight of combining just the right words in just the right way, and revel in creativity and wonder and enjoyment. We need to add this type of writing to our students’ experience of writing paragraphs, essays, and other academic-style assignments.

As Anabaptists, we are a very practical people, and there are strengths to that. We like things to function well in tangible ways. But we forget that we can’t always measure the value of something simply by how useful it is. Sometimes, the purpose of writing can just be writing.

I want to clarify that there is definitely a place for structured writing—of teaching students how to craft specific formats like essays. But not all the writing we ask them to do should be formulaic, informational-style assignments.

Ruth Culham talks about formulaic writing assignments and points out, "If writing is thinking, this approach doesn't move students toward that goal." She also says, "I believe the person holding the pen is the one doing the learning.”

We need to teach our students how to hold the pen themselves, and at times that involves giving them freedom in what they write and how they write.

The Bottom Line

In short, writing is about shaping our student’s minds to think differently. Pam Allyn says, "Living a writing life is living with our eyes wide open." When we turn our children into strong writers, we are teaching them to see well and to speak well. And that is a gift that our students desperately need.

Smith, Dave. The Quotable Walt Disney. United States: Disney Book Group, 2015. Culham, Ruth. Teach Writing Well: How to Assess Writing, Invigorate Instruction, and Rethink Revision. Stenhouse Publishers, 2018. Pam Allyn. Your Child's Writing Life: How to Inspire Confidence, Creativity, and Skill at Every Age. Penguin, 2011.

Guiding Students Through the Process of Writing Research Papers

Research papers are probably the most daunting of all assignments for school students. Keeping that in mind, these steps are designed for younger students (grades seven and eight) or for high school students who are unfamiliar with the process of writing a research paper. Our goal is that students will be able to do this on their own after they are comfortable with the process.

First of all, timing can be almost everything. The first two semesters of the year aren’t a good time to begin research papers because it’s too early in the year. It’s better to wait until students have learned a little more. The last quarter isn’t a good time either as most of them have spring fever and will be looking out the window. But I have found that the third quarter, around January and February when it’s cold and dreary outside, is a good time to work on research papers.

Orientation for you

- January-February: Begin research papers in small steps.

- Provide 3-pronged folders with pockets and notebook paper. Each step of students’ work will be turned in inside this folder.

- Usually do one step per day in class together. You will be telling the students exactly what to do, then they will be working on their own with their specific topic. Your instruction takes up about half of the period, depending on that day’s task.

- Give students good examples for every step. Read them aloud. I usually choose a topic that no one in the class has chosen, or the one topic that my most struggling student has chosen to use as an example. This gives them all an example to follow, and really helps the struggling student.

- For most topics at this level, try to get them to think chronologically as this helps them organize their outlines. Any history topic can be done this way. I give most examples orally, because if I write them on the board, they usually copy what I write.

- Give students a grade on each little step. (Accountability!)

Instruction plan

Day 1: Choose a topicBreak: Gather encyclopedias, order library books, etc. Resume when each student has three to five sources. I order books from the library and pick them all up to put in my classroom.Day 2: Title and Outline Day Titles should be grand! Give them some super-amazing title examples. Don’t allow anything boring or mundane.Day 3: Bibliography Card Day Write a sample on the board. Walk them through the process. Be patient. This task is really hard for younger students.Day 4: Note-taking, Day One Again, write a sample on the board. Super important: Remind them to jot down phrases to prevent plagiarizing. I encourage my students to have three bullet point phrases per card—all on the same topic, of course. Our goal is to complete about ten notecards or more per dayDay 5: Note-taking, Day Two Day 6: Note-taking, Day Three (Add another day if students need more time or if more sources and notecards are required)Day 7: Introduction Writing Day Give great examples. Be a little dramatic. This will produce much better writing. Encourage students to write two introductions (begin with an amazing fact from their research, a true story, a question, a definition, a quote etc.) and then choose their favorite.Day 8: Note Card Organization Day Using their outlines as a guide (and encourage students to update their outlines if they have found different information than they had planned), make stacks of notecards based on the information they cover (Introduction, Roman numerals I, II, III, etc., Conclusion) Then have students organize each individual stack into the order they want to write it in. Use rubber bands to secure the packet of cards.Day 9: Begin Rough Drafts Day With their note cards in hand in the right order, encourage students to get as much done well as they can. “Focused and fast” is how I tell mine to approach their first draft. I also make sure that they have a cardstock copy of the “Transition Words” and “Different Ways to Begin Sentences” handouts on their desks.Day 10: Finish Rough Drafts Sometimes I let them do this in class, but usually I give students about 3-4 days to finish these up on their own.Day 11: Rough Drafts Due On a Thursday, on time! No excuses. (Don’t ruin your students’ weekends by making these due on a Monday or Tuesday.)Break: Take a week or two break to allow time for student to have a mental break and for you to diligently grade their papers.Grading research paper rough drafts

- Mark or circle anything wrong in colored ink. Use editing marks but do not correct them – just draw the students’ attention to the fact that something is wrong and expect them to fix it.

- Put a squiggly line under anything that is acceptable but sounds like a first grader wrote it. This could be a single word, or a phrase, or a sentence. Encourage students to rewrite these parts. Also write “awk.” on anything that sounds awkward and needs to be rewritten.

- Give two grades: a content grade and a mechanics grade. If they fix all the mechanics they could get a final grade as high as their content grade. If their content isn’t good, tell them what is wrong and how to fix it (add pages, rearrange, rewrite parts, etc.)

- I like to base their final grade largely on their rough draft grade, adding points where they’ve earned them. If they fixed all the mechanical errors, that grade goes up, and if they rewrite, reorganize, and fix whatever I had noted on their rough drafts, their content grade will go up. I usually average the two for their final grade.

This is a summary of a much longer in-depth description on guiding students through research paper preparation and writing, and editing. If you are interested, our guide “It’s Research Paper Time” is available by contacting us at littleflock7@gmail.com.

Quick and Easy Formative Assessment

Does Johnny deserve an A? Did Susie answer enough questions correctly? Can Janie read the proper amount of words from this list? Sometimes assessment is easy, if there is a definite right/wrong answer or if the answer key explicitly tells how to grade the question. But sometimes assessment is more difficult if there are several possible correct answers or if an essay is involved.

Assessment, or seeing how much the student has learned, can be either formative or summative. Summative assessment occurs at the end of a learning unit, while formative assessment focuses on identifying students' progress throughout a unit or grading period. Its purpose is to uncover students' ideas and knowledge before a final grade is issued, giving both the student and the teacher a chance to make changes in the learning process. Often with formative assessment a grade is not given, but the teacher receives needed feedback to create proper lesson plans.

Several practical formative assessments can greatly aid the teacher. One quick method for the elementary teacher to assess student mastery of a single lesson is to use �traffic lights.� The teacher issues each child three craft sticks or stop signs: one red, one yellow, and one green. The student holds up the appropriate stick when asked to do so to represent his current level of understanding. Red implies that the child completely lacks understanding of the concept. Yellow means that he has partial understanding, but would not be able to explain the concept to someone else. Green shows that he both understands the concept and could explain it to someone else.

This can also be modified for use with older students. Instead of using craft sticks, the teacher can give the middle-school student colored cards to hold up. Even that might seem childish to the high-schoolers, so for those grades, students can color-code their papers or sections of their papers: red underlining or highlighting for parts they completely don't understand, yellow for those sections they need help with, and green for the portions about which they are confident. This is especially helpful in editing writing assignments.

A second strategy of formative assessment is a teacher chart for noting observations about students throughout the year. The teacher creates a chart for the entire class, labeling columns with dates and rows with student names. Throughout the time period assigned to learning the particular objective, the teacher observes each student briefly for the same goal, such as participating in class discussion or reading fluently. Then the teacher briefly notes the student�s performance and can track their progress or lack thereof for that specific goal. The chart can be laminated and written on with erasable marker so it can be used again for a different goal.

A third formal assessment strategy is entrance slips used at beginning of class to ask the students a question from the day before, ask them preview questions of the current day's topic, or provide them with a chance to give feedback. Many teachers use exit slips at the end of class, but do this at the beginning allows the teacher instead to see what students remember the next day or where they still need help. These can be adapted to work for any class and grade level. Even young students could draw pictures to respond to a beginning-of-the-day question.

So whether Johnny deserves an A or Susie answered enough questions correctly or Janie can read enough words can sometimes be difficult to identify. But by using formative assessment throughout daily lessons, the teacher can more easily determine student progress.

About Those Raised Hands

I have to wonder at what point in history the raising of hands for permission to speak became such a ubiquitous part of the classroom. It�s really a bit odd when you think of it, yet it is a helpful signal that can serve us well if we use it wisely.

Certainly, the practice of speaking in turn is a vital skill for students to learn. In conversation with some teacher friends, we have wryly concluded that if by some magic students would always speak up when we want them to, and if they would never talk or whisper without permission, the single most frustrating aspect of school teaching would be eliminated. If such magic exists, I have yet to discover it. Instead, I walk the daily delicate balance of trying to maintain order while making my classroom a safe place for students to converse and to share their thoughts.

While the raising of hands can be a useful signal, it is important to remember that raised hands should never control the classroom. First, we should never feel obligated to answer all the hands that are raised. Students should know that raising their hands is not an automatic ticket to get to talk at that particular moment. While I don�t want to shut down the enthusiasm of youngsters eager to share their thoughts, sometimes it is necessary to say, �Ok everyone, put your hands down. For now, you need to listen instead of talk.�

My students use different hand signals if they need a tissue, need to sharpen a pencil, etc., so I don�t need to be afraid of ignoring needs by not answering every raised hand. It still takes good discernment to know when to call or not to call on some of those persistent hand raisers. At times when I have found myself falling into the ditch of answering unnecessary hands that take a lesson off track, I have often recognized that it is because of laziness or lack of preparation on my part.

The flip side of this is that it is also important to call on students who are not raising their hands. In his excellent book, Teach Like a Champion, Doug Lemov calls this practice �Cold Call.� Out of the forty-nine practical teaching techniques described in his book, Lemov says �Cold Call� is the �single most powerful technique� that fosters high classroom achievement. If students know that they may be called on at any point in a lesson, it will keep them on their toes. The goal of this should never be to put students on the spot or to embarrass them when they weren�t paying attention. Instead, the goal is to drive classroom engagement and to give every student the chance to share their thoughts, even the shy students who are reluctant to raise their hands.

I have found �Cold Call� to be remarkably effective in my own classroom. I tell my students plainly, �I might call on you whether or not you are raising your hand. It�s ok if you�re not sure about the answer. You can give it a try, and if you get it wrong, you can learn from your mistake.� Consider the difference between these two approaches to a very simple question in math class:

- I ask, �What is the eighth month of the year?� Five hands go up. I call on someone who is raising their hand, and they give the answer.

- I say, �What is the eighth month of the year? Use our Months of the Year chart to figure it out if you don�t know by memory, and soon I�m going to call on someone to give us the answer.�

In the first approach, maybe half the class is engaging with the question. Using the second approach, suddenly everyone is engaged, because they know that they might be called on to give the answer. �Cold Call� keeps students accountable and encourages everyone to interact with every question.

Managing the raising of hands (or not raising hands) demands constant wisdom and attentiveness for us as teachers, and it is an important part of everyday life in the classroom. It is our responsibility to guide classroom discussions in a way that will maximize engagement and learning for our students.

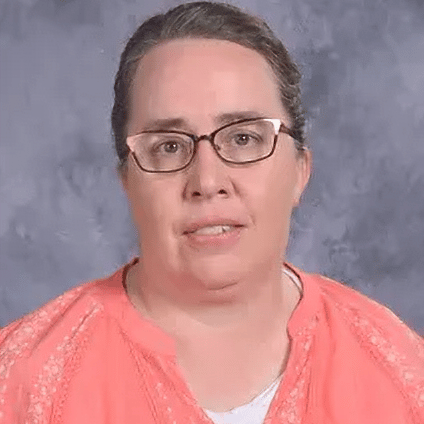

Types of Teachers

Your students know if you care, and I think they know if you don't care, and I think they know if you don't care and you try to fake it. Their radars are pretty good with that. So I would encourage you to do everything you can to prepare to care for them and to be a blessing.

All right, types of teachers. You can't pigeonhole everybody. These are a little bit caricatures, but I want you to think about them because you may fit into one of these and you don't think you do. All right, I have, and I ain't going to tell you which ones. So, um, kind of making light of some things that we want to avoid and then some of these that I hope that we can all grow into as we mature.

�Trying to Be Cool�

The "Trying to Be Cool" teacher. It's important to them to be relevant to the student. And this is not a thing for 22-year-olds or 18-year-olds. Oftentimes it's 30, 35, 40, where we start feeling like, �Well I kinda would still like to be kinda cool.�

You're not.

And so we're kind of relevant. Some problems with it, and you know what it is, so you dress like it was cool when you were cool 20 years ago. I'm not trying to teach you how to be cool, but not only are you not, but students are like, "This is really awkward. If you'd just be a man or a lady."

Part of this is oftentimes these kind of teachers have short lived popularity. They need to be very popular for three weeks of school, and then something just clicks, and it's not that attractive to students, really. I've noticed that these kind of teachers can gain classroom management quickly because the students think they're pretty cool, and then after two or three weeks, you're pretty cool, doesn't help them to know when they can or can't talk or when they can or can't do anything. And then it's a nightmare, and they don't favor that teacher anymore.

�Trying to Be Just Like a Student�

So teacher B is "Trying to Be Just Like a Student." This is different than trying to be cool. Remember, even if you're an 18-year-old teacher, the students probably view you more closer to the age of their parents than you realize. They really do.

My band director who I loved in high school, he was about 28 years old. I was 14. My parents were 34, 36 years old, and I was pretty sure they were all the same age. Think about that. I added eight years to the guy's life. They were just all adults.

So I know some of us think, �I'm 28, I'm young.� Students are looking at you thinking, �You're 28, whoa.� Know what I mean?

You're old. And so I just wouldn't worry about it.

It's tempting sometimes even for older adults to try to dress and act like students and do the things that they do. Remember when you were that age, which is such a valuable resource: remember what you did. Oftentimes they're doing things because the other students are doing it. Not really because they even think it's that cool. That's what you do.

And so I think there's some destabilizing effect for them trying to see adults try to be like they are when they're being like they are, just to fit in, and they might just hate it.

So my band director, he was 28, which in my mind, honestly, he was the same age as my parents. He showed up once, there was a musical performance, and we saw him, and it was outside, and he came up, and it was in the mid- eighties, and he had these super long short pants, and that's what people wore, and he said something about it. He said, "Do you like my short pants?" We didn't say that. We would of just said shorts. And I just was thinking, �I can't believe he did that.� And it wasn't immodest or anything. I mean, they were longer than short shorts or whatever, but I mean, he was trying to look young, and I just remember thinking�I loved him, I still do, I love all my teachers�and I just think I thought, �This is just weird. Why is he doing that?� I was really disappointed. It kind of took him down a few levels because he was really trying to be relevant that way.

Anyways, my children�and you don't need to try to guess who I'm talking about. I've taught in a Baptist school, a non-Anabaptist evangelical Baptist school. I've taught in Mennonite schools, I've taught in a Beachy school, I taught in a Charity school, and now I teach in a school where we have everything. We represent about 30 different churches, Mennonite denominations, and about seven or eight different Mennonite denominations within the 30 churches.

So don't try to guess.

So my children said once they had a chapel and a teacher got up and started talking about how young he was and how he was actually closer in age to the students than he was to the rest of the teachers. And he was very relevant with technology, and he said, "I'm just like ya'll. I have Instagram." So we all have Instagram, okay? And Facebook. And he went down the list of things, and my children came home just like "I just can't believe he said that. Why was he trying to show us that he was just like a student?" And honestly, if he was two years older than them, they probably thought he was 22 or 23 until that.

So if you are one of those adults that can be relevant just because you are, then that's one thing, but don't try it. Don't try to be just like a student.

�Trying to Be an Important Authority�

"Trying to Be an Important Authority." This is the person that's like, �I am a professor.� And you can tell when you meet them that they're the professor. They're smart and you're dumb. I mean, just simple things that they say in life are just "I'm smart." It's all with authority. And they tend to view teaching as an opportunity to be in charge of other people and to be important. And they want to appear very wise, but then they're like it's like a sage, like just this wise old person and that's like their thing.

Why would you want to do that?

It's very important that you view them as smart and they use big words to try to impress you. Have you ever known somebody who was truly intelligent, that was really smart? And they didn't use big words and you can just tell it as soon as they open their mouth: this person is really quite brilliant. And they don't try to use words or use fancy words wrong. Makes it worse.

�The Flirt�

The next one tends to be a guy, doesn't have to be is "The Flirt." And I don't want to make light of this one. It's "creepy teacher" and I don't think you realize this, why it's happening. And I put this somewhere else. Anyways.

This very well could be the first time, when a guy teaches, that women have ever paid him any attention in his life. Suddenly you're in charge and you're the teacher and you're speaking and girls are looking at you.

In some ways you can make it humorous. I just don't think guys process it all. And I think it can lead to irreverent, probably at first, for sure, accidental behavior or something like that. We're going to actually talk about this more specifically.

So I just put: don't sit with girls. Don't sit with girls. I don't like to sit with lady teachers. It's just weird and inappropriate anyways. Don't ever be in a closed room. Billy Graham Rule. We'll talk about that in a minute. People are watching you. Even if you feel like you're keeping it professional, when you talk to the same person over and over about school, it's awkward and it's just not right. And it's, I think, pretty hard to shake that image even if you mend your ways.

�The Mature, Secure, Stable Human Being�

"The Mature, Secure, Stable Human Being."

Usually interesting people. It can take a little while of maturing to get to be that way because you do want to work through being cool, being like a student, the important authority guy�if you are a flirt than that.

So at one point in my life I was like cooler than I am now. Don't laugh, okay? I was. All right, I was in my early thirties, and I really thought I knew how to relate to students and young people better than people that were older than me. And I was a music teacher and I dressed a little bit cool. Don't mock me, okay? I'm just saying. And so I noticed that sometimes I had one or two students, like drop my class for this other teacher that was about 45 years old, little man beard, kind of nerdy hair, if you know what geek hair is, and soft spoken. He's very, very intelligent and he taught advanced math and he taught psychology. And I'm just thinking I'm the one that kind of--forgive me. Okay, I don't think like this. It was a long time ago and I just thought, �Why are they going to his class? I'm like cool and I'm more relevant than he is.�

And I thought about that for years and it just makes perfect sense to me. He's a stable guy. He could be most of those students� dad�s age. He was interesting. He's pretty caring. I remember observing a class of his, it was an advanced math class, and the students were all talking, talking a lot, talking a lot, talking a lot. And he went up in front of class and he went there and he said, "Okay, we're going to start class now, if you can open your book." And it was silent.

That's awesome. To me, that's more than having a class silent when you walk in there the whole time--is if they can talk and if there's enough respect and culture there, that when you start talking, it's done. I've striven for that actually, in our high school.

So just think about that. It's interesting. It's kind of a dad. I think it would be a goal for us men to be at some point in your career, a big brother and work on our way when you're 35 or older, really to be the dad.

And the ladies, the same thing. They're your little sisters. Even if you're in the same youth group and you're their teacher. Big sisters. And then if you're still teaching, ladies, and you�re a career teacher, the mom figure�it's a blessing to be that way.

�The Youth Counselor�

Okay, "I Want to Be Your Best Friend" / "Youth Counselor.� In the 1990s and 2000s, evangelicals really got into this culture of youth pastor and youth pastors were very charismatic and it's still around and I think it's crept into our cultures a little bit. Younger people with young families, a lot of mentoring. Mentoring is good. It just needs to be structured and mentors need to have mentors.

And so they were adults that were pretty cool. Spending an inordinate amount of time probably with young people and I've seen that sometimes even in our schools.

And so what that can cause is that the teacher that does this and the students that he's involved with kind of view themselves as cooler than everybody else and cool becomes a big deal. And it's hard to relate finally to that teacher's authority because the relationship was built on that and then really hard to relate to other teachers who are just normal trying to do their thing.

My students are my friends. I don't tell them that until they graduate. My children are my best friends in the whole world. Even when they're like five. Some people say they're not their friends until they graduate. I just don't tell them that. But they are. We just love them. And I love my children so much. My biological children, I love them and they're my friends. So, yeah, our students are our friends.

But the best friend thing, that's just not appropriate, I think, when you're their teacher.

�I Make Fun of Mennonites�

The "I Make Fun of Mennonites Guy." You've probably heard of teachers that are just getting a little frustrated with our culture so they make fun of Mennonites to the students.

So I'll bring up the second point first. You probably shouldn't be teaching Mennonites because you don't like Mennonites. Right?

That's funny. Why is he here?

Second one is, I mean, there's a teacher and he just kept giving digs at the plain suit, digging at the plain suit, digging at our culture. And the crazy thing is, some of the youth that were in a part of�well I won�t tell you, don�t want to give anything away�but anyways but I knew some of these youth, even some of the cooler youth that might not have been huge plain suit fans, they're kind of offended that their teacher was just giving those digs to plain suits.

We get so whacked out comparing ourselves with the world. If you're a worldly person, it's like cool to wear a plain suit. It like always has been. That's like what famous people do. But we look at it and think, well, we have to. And so the whole thing, just wear the thing. Anyways.

So we just shouldn't give digs at our own culture like that. That's a terrible thing. I understand other digs, if you're in a school and you don't like the curriculum for whatever reason, just don't do digs to our culture. We're here to build up a culture that I think is a beautiful thing that we have.

And the last one�the outline I gave you is like five days old. Teachers edit these things until like an hour ago. My notes have more than yours.

�The Cheerleader�

"The Cheerleader." Just be a cheerleader. Can you think of a blessing? I realized that we don't want to make our students all proud by blessing them. I'd rather bless my students. I just love them. Especially since I get to teach K-12 every day. Especially those little ones. Just bless them.

Our students at Shalom wear uniform. So all I've got to bless them on is the girls, how they braid their little hair, the guys and their little belts, and their shoes, and their watches, and the girls and their shoes. And I love shoes anyways.

Be a cheerleader. Tell them how much you like what they do. It's okay. I really don't think that's going to make them egomaniacs. I just think it's nice.

Isn't it nice when somebody says something nice to you? It feels good to me. If I get a bad note from a child and I can't tell what the writing is and I don't know what the picture is that they drew, my day is made. That's it. It is made. I got something�a piece of candy on there, a poorly colored picture of a horse. My day is made. It's so nice.

Think Barnabas the encourager. Can we be that way to every single student you have? Every single day? Even the cool, tall basketball guys. It feels good.

I had one guy I told him�I love shoes. I like Vans. Childhood thing. Anyways, and Converse. And I just said, "You got Vans on. That looks nice." And he told me years later, he said, "I felt like I was on cloud nine because you said that to me."

And I really meant it. I really do like Vans. I don't like Dude shoes as much, so I won't say that, but they're interesting. But you know.

I had no idea it impacted this guy. He said, "I felt so good." That was the first day of school. "You found me and you met me and you said you like that so."

Full of Compassion

How can I develop and grow in compassion? I remind myself that God loves each child – God loves everyone, and I need to see people through His eyes, and love with His love. Each person is valuable. I should pray for my students by name. I will pray for myself to be compassionate. I will make an effort to find positive things in each student and let them know what I see. I can purposefully reach out to the students, talk to them, and take an interest in their lives. I should think about their lives. Maybe there is a new baby at home, or a special needs sibling, and my student isn’t getting as much attention at home just now. I will try to give them extra attention at school. I will empathize with the children. Think of all the kinds of people that Jesus talked with, loved, healed, worked with, and had compassion on! I want to follow His example.

When a student rolls his tongue in his mouth, I think he is feeling nervous and unsure of himself. Maybe I have been pushing him too much, and not showing the compassion that I should. I need to remember to gently remind him what he needs to do and guide him in following directions. I will listen to his stories that don’t fit in with anything and give him importance.

I think Ephesians 4:32 embodies this desire to be “full of compassion.” “Be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you.” (ESV)

*Song: “O to be Like Thee” by Thomas Chisholm

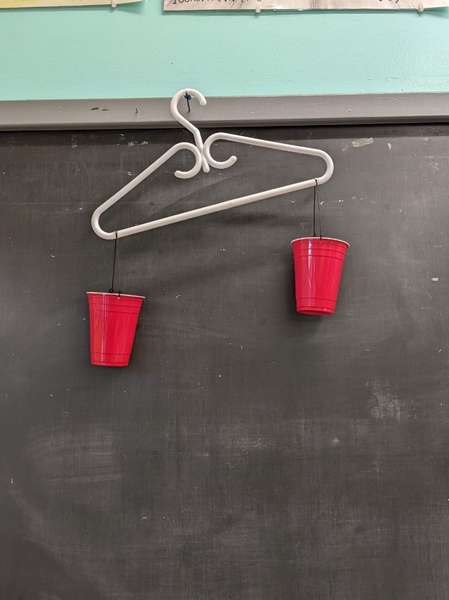

Tipping the Scales to Teach Basic Algebra

This is the story of how two plastic cups, a coat hanger, and some string revolutionized the way I teach algebra.

It started one year when I was teaching my sixth graders some introductory algebra—basically a lot of solving for unknown variables in addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division equations by using the inverse operation.

My students were struggling with the concept, and I couldn’t figure out why. One breakthrough came when I realized they had a fundamental misunderstanding of an equal sign.

It seems so basic, but in the lower elementary years, students are subconsciously trained to think that an equal sign means you need to do something. They are given pages of math facts like “9+1=__” and told to solve them. Most of their experiences with equal signs require them to write the answer following the sign, hence the mindset that seeing an equal sign calls for an action from them.

Really, though, that is not what an equal sign means. Rather than being an instruction for action, it is a description of reality. It is simply saying that what is on one side of the sign is the same as what is on the other side of the sign. 9+1=10 because 9+1 is exactly the same thing as 10; it’s just a different way of saying it. Helping students understand this is essential to their ability to understand algebra.

A helpful analogy is to compare the equal sign to a balance scale—what is on one side of the sign must be exactly the same amount as what is on the other side; otherwise it isn’t truly equal. After spending some time looking at balance scales on Amazon and deciding they were out of my price range, I crafted a simple DIY version out of two cups suspended from either end of a coat hanger.

It’s not perfect, and it’s certainly not completely precise, but it gets the idea across.

I used marbles as my “numbers,” but you could use any objects as long as they are all the same size, shape, and weight as each other.

I started at a basic level with my students, as I wanted to break down their root misconceptions about the equal sign. We spent some time physically placing marbles in the cups and having them answer questions like the following:

If I have 4 marbles in the first cup, then I add 5 more, how many marbles would I have to put in the second cup to make the scale balance? What is the mathematical equation for what we just did? (4+5=9)

If I have 7 marbles in the first cup, then I take away 2 of them, how many marbles would I put in the second cup to make the scale balance? What is the mathematical equation for what we just did? (7-2=5)

If I put 3 groups of 5 marbles into the first cup, how many marbles would I put in the second cup to make the scale balance? What is the mathematical equation for what we just did? (3x5=15)

I spent as long as I needed to on this step until I was sure my students understood the concept. Once they did, I knew they were much better prepared to understand conceptually what an algebraic equation is saying.

The beauty of the balance scale goes a step further, however.

I prepared my scale before class with something like this:

In the left cup, I had five loose marbles and four concealed to be “x.” I simply wrapped four marbles in paper towel and used a marker to draw an x on the package. You could hide the unknown amount however you wish—I like paper towel because it’s fairly lightweight and shouldn’t throw off the equilibrium of the scale too much. (Although since the coat hanger scale is questionable in its exact accuracy anyways, you can get away with more than you could with a real, precise balance scale).

I then filled the right cup with 9 marbles so that the scale was balanced.

When class time came, I showed the students what was in each cup. We worked together to write an equation to illustrate what was on each side of the scale. (x+5=9)

Then, I said, “Now, you might already know what x is in this equation just because of your knowledge of math facts. Pretend that you don’t. Your task is to come up with a way to know how many marbles are in the x package without using math facts and without opening the package. You may simply add or take away marbles from the cups.”

And then I let them wrestle over it together. We tried their ideas until we found one that worked. I found it was such a great way to force my students to engage with the underlying concept, not just give them step-by-step instructions of how to solve the problems.

There are different ways the students can think of to solve the puzzle, and that is fine. Like most things in math, there is more than one path to the right answer, and it’s good for them to see that.

However, regardless of their method of solving the problem, I always conclude by taking the time to walk through exactly what happens when we do the steps we will learn to solve the equation x+5=9.

- We want to get x by itself, so we take away the 5 other marbles, leaving only the x package.

- Notice that the scale is unbalanced. We don’t want that, or else our equal sign isn’t true.

- Do exactly the same thing on the other side (remove 5 marbles), so that the scale balances again.

- Count how many marbles are left in the cup on the right side. Realize there must be 4 marbles on the left side, too.

- Check if we’re right by opening the x package.

And suddenly, for my students, algebra was no longer this strange, nebulous world where we inexplicably added the alphabet to math and nothing made sense anymore. It took more time and effort than teaching them a list of steps would have, but the pay-off of them actually understanding what was happening was priceless.

I used the same visual representation to teach multiplication equations. To illustrate 3x6=18, for instance, I made three paper towel x packages with six marbles in each for one side of the scale. The other side got 18 loose marbles. We then solved by taking the 18 loose marbles and dividing them into three even groups, resulting in six in each group.

I found it worked best for showing addition and multiplication problems, though you could illustrate subtraction and division too, if you wish.

Another time the balance scale helped my students was when they first encountered an equation that was written backwards of what they were used to. After seeing equations such as x+3=12, suddenly having it written as 12=x+3 can be confusing for them. All I had to do was walk over to my balance scale and flip it around. The understanding that dawned in their eyes without me even saying a word was a beautiful thing.

Sometimes, knowing how to counter student confusion can be difficult, especially when it’s rooted in deep, conceptual misunderstandings. But for me and my students, confusion about algebra was solved with a few simple household objects and a bit of imagination. I hope it can do the same for you.

Privacy Policy

How we handle your personal information

What personal information do we collect from the people that visit The Dock?

When you fill out a form on The Dock, or sign up for an account, you will be asked to enter your email address, information about your educational roles, and other details as appropriate to maintain consistent quality for all users of The Dock.

When visitors leave comments on the site we collect the data shown in the comments form, and also the visitor�s IP address and browser user agent string to help spam detection.

An anonymized string created from your email address (also called a hash) may be provided to the Gravatar service to see if you are using it. The Gravatar service privacy policy is available here. If you use Gravatar, your profile picture is visible to the public in the context of your comment.

If you upload images to the website, you should avoid uploading images with embedded location data (EXIF GPS) included. Visitors to the website can download and extract any location data from images on the website.

When do we collect information?

We collect information from you when you register on our site, fill out a form or enter information on our site.

How do we use your information?

To improve The Dock in order to better serve you.

T o ask for ratings and reviews of the content on The Dock.

To follow up with you by email or phone regarding a technical support or content question.

How do we protect your information?

Your personal information is contained behind secured networks and is only accessible by a limited number of persons who have special access rights to such systems, and are required to keep the information confidential. In addition, all sensitive information you supply is encrypted via Secure Socket Layer (SSL) technology. We implement a variety of security measures when a user enters, submits, or accesses their information to maintain the safety of your personal information. All donations are processed through PayPal and are not stored or processed on our servers.

Do we use �cookies�?

Yes. Cookies are small files that a site or its service provider transfers to your computer�s hard drive through your browser (if you allow) that enables the site�s or service provider�s systems to recognize your browser and capture and remember certain information.

We use cookies to

Understand and save user�s preferences for future visits.

Compile aggregate data about site traffic and site interactions in order to offer better site experiences and tools in the future. We use trusted third-party services that track this information on our behalf.

How we use cookies, and how you can manage them.

If you close a pop-up or message bar on The Dock, a cookie is set to help us avoid showing you that message again.

We also use Google Analytics cookies to help us compile aggregate data about site traffic and site interaction so that we can offer better site experiences and tools in the future. These cookies do not identify you personally, but they tell us your location and, in many cases, your device and your demographic information.

If you leave a comment on our site you may opt in to saving your name, email address and website in cookies. These are for your convenience so that you do not have to fill in your details again when you leave another comment. These cookies will last for one year.

If you have an account and you log in to this site, we will set a temporary cookie to determine if your browser accepts cookies. This cookie contains no personal data and is discarded when you close your browser.

When you log in, we will also set up several cookies to save your login information and your screen display choices. Login cookies last for two days, and screen options cookies last for a year. If you select �Remember Me,� your login will persist for two weeks. If you log out of your account, the login cookies will be removed.

You can choose to have your computer warn you each time a cookie is being sent, or you can choose to turn off all cookies. You do this through your browser settings. Since browser settings vary, look at your browser�s help menu to learn the correct way to modify your cookies.

If you turn cookies off, it won�t affect your experience except that your site preferences may not be saved and you may need to log in in order to use the Favorites feature.

Third-party disclosure

We do not sell, trade, or otherwise transfer to outside parties your personally identifiable information.

Third-party links

The Dock includes links to third-party products or services as well as content embedded from third-party sites such as Vimeo. These third-party sites have separate and independent privacy policies.

Embedded content from other websites behaves in the exact same way as if the visitor has visited the other website.

These websites may collect data about you, use cookies, embed additional third-party tracking, and monitor your interaction with that embedded content, including tracing your interaction with the embedded content if you have an account and are logged in to that website.

We seek to protect the integrity of The Dock and welcome any feedback about these links and content.

How long we retain your data

If you leave a comment, the comment and its metadata are retained indefinitely. This is so we can recognize and approve any follow-up comments automatically instead of holding them in a moderation queue.

For users that register on The Dock, we also store the personal information they provide in their user profile. All users can see, edit, or delete their personal information at any time (except that they cannot change their username). Website administrators can also see and edit that information.

What rights you have over your data

If you have an account on this site, or have left comments, you can request to receive an exported file of the personal data we hold about you, including any data you have provided to us. You can also request that we erase any personal data we hold about you. This does not include any data we are obliged to keep for administrative, legal, or security purposes.

General safeguards

You should know that

You can visit The Dock anonymously.

You will be notified of any Privacy Policy changes on this page.

You can change your personal information by emailing us or by logging in to your account on The Dock.

We honor Do Not Track signals and do not track, plant cookies, or use advertising when a Do Not Track (DNT) browser mechanism is in place.

We do not allow third-party behavioral tracking.

We do not specifically target children under the age of 13.

Email privacy

We collect email addresses in order to send updates and respond to inquiries

For regular email updates from The Dock, we agree to

Not use false or misleading subjects or email addresses.

Identify the message as an update from The Dock.

Include the physical address of The Dock.

Monitor third-party email marketing services for compliance, if one is used.

Honor opt-out/unsubscribe requests quickly.

Allow users to unsubscribe by using the link at the bottom of each email.

Summing it up:

We have a strong interest in maintaining privacy. We never sell advertising on The Dock, and we will make it our goal to treat your information with the same honor we want our own to be given.

Contacting Us

If you have questions or concerns regarding our use of your information, you may contact us on the contact page or use the information below.

The Dock

28527 Guys Mills Rd

Guys Mills, Pennsylvania 16327

United States of America

dock@thedockforlearning.org

Dedication: Making Any Curriculum Work in Your Classroom

Dedicated teachers should be able to make just about any curriculum work well for their students. It may be challenging, frustrating, and take some extra time, but the rewards are well worth it. Your students will be able to comprehend the material in a more meaningful way, their grades will improve, and you will feel more effective as a teacher.

The first and probably most common problem is that the material is too complex and over the students’ heads. Their earlier years haven’t prepared them for it, or perhaps it’s just a very progressive curriculum. Sometimes the concepts in the curriculum aren’t that advanced, but the examples in the book are complicated or confusing to students. Because it is still your job to help them to comprehend the material, you do have a few options in this case.

- Read the teacher’s guide and see if there are suggested chapters you may omit as the publisher has deemed them “optional.” I’ve used pre-algebra textbooks that recommend alternatives such as skipping the chapters on base ten numbers, computer programming basics, and beginning calculus concepts.

- Teach the concepts as clearly as you can and find alternative ways of presenting them. I’ve developed and used my own examples of material in my lessons, found more basic worksheets for recognizing and diagramming verbals, typed out worksheets, and made study guides or slideshows to help students understand the textbook material in a more palatable way.

The second issue is often that the concepts presented in the texts are within the students’ grasps, but the homework assignments are too tedious and repetitive. In this case, students get bogged down. The first page or so of the exercises or homework they do well, but then they get brain fatigue and begin to get careless. If several of your students are spending hours on homework, that is probably the case. I asked a more experienced teacher a question about this once, and got some great advice: just have students do the odd numbered problems.

A third issue may be that students lack the ability to sift through major concepts, details, and effects. They aren’t sure exactly what the important facts are, and what are just supporting facts or information. Often just focusing on main concepts can really help students comprehend the material in a more organized way. Study guides, outlines, and writing primary concepts on the board will help those students, although they should be encouraged to be able to do this on their own over time as they follow your modeling.

The last issue is that sometimes the material is just too easy for the students (or for some of the students), and they tend to not try as hard because an A is almost effortlessly achieved. In these cases, the material needs to be supplemented, and students need to be challenged. There are several ways to do this.

- Find the weak spots in the curriculum or textbooks and add to it. If an English curriculum is strong on grammar content but weak in other areas, assign short daily writing or journaling assignments, focusing on a variety of styles. If it’s weak in literature, find additional short stories, trade books, or anthologies you could use to supplement it.

- If you finish an entire book and have time left over the last month or so of school, find a unit study and delve into a more specific topic. You can add science experiments, a building or writing project, or anything else that you or your students want to learn more about.

- Challenge students to do more. If students are required to have three variables for a science fair project, challenge them to have five.

If the textbook requires a four-page written report and forty notecards, challenge them to have five or more pages and fifty notecards. I once had an eighth grader turn in an eighteen-page research paper after I issued this challenge.

Teachers have the responsibility to teach their students the chosen material, even in situations where it might not be ideal. Dedicated teachers will work diligently to find ways to adapt the textbook contents to better fit the needs of their students, whether it be breaking it down into manageable portions, presenting the material in different ways, or challenging students to achieve more. It can be done, and your students will benefit greatly from it!

Top Five Practices for Science Class

When I think back to when I was in school, I think science was my least favorite subject. It didn’t make sense to me, and I thought it was boring. Now that I’m teaching, science is one of my favorite subjects. Doing these five steps made the difference.

- Do every experiment in the book. You’ve got to plan a little ahead to do this, but it is so worth it. Before school starts, get a bin and collect everything that you will need to do the experiments, or at least look a day or so ahead and get the supplies that will be needed. Students learn about four times as much when they see actual things being done rather than just reading it in the book, although we should always read it in the book, too.

- Keep science sketchbooks. Give each student a blank sketchbook with no lines. As you are going over the lesson, encourage students to draw (using colored pencils) and label the main points of what you are studying that day. While my students do write the vocabulary terms and short definitions for them in these books, most of the content in the sketch books consists of drawings with color and arrows to show movement. I always tell my students what to draw and model it for them on the board or in my sketchbook. That way they can see exactly what I expect them to write and draw, and this avoids many questions.

- Learn outside of the books. Grow plants in the classroom. Place a bird feeder near a classroom window and identify birds. Encourage and even reward students for finding fossils, bones, unusual leaves, or anything from God’s creation. Have them bring these into the classroom for everyone to see.

- Find as many tangible examples of what you are studying in the book as you can. These can be found inexpensively at garage sales, thrift stores, online, or for free if your students find them and bring them in. To look at pictures in the book is nice, but your students will learn much more if they identify the types of clouds at recess or hold a piece of granite, a cow femur, or a fossil in their hands.

- Go on nature walks during recess. While we will often find examples of what we have been studying in science on our nature walks such as windmills, rock samples, plants, insects, mammals, etc., sometimes we will not, but we will always look for and find some type of interesting science item and enjoy the fresh air and exercise while we do.

True Springs

In the early 1900s, the town of Winona Lake, Indiana, was a summertime destination for many Christians. Cultural Chautauqua speakers and events mixed with a three-week Bible conference in a beautiful lakeside setting to provide a summer vacation for Christians from around the world.

One of the drawing attractions for the visitors was a series of natural springs gushing from the hillside around the lake. The most unique spring was called the Tree Spring. Every day, guests would line up with their metal cups to get the fresh water that gushed from the spring in the middle of a maple tree trunk. The tree spring was reported to have vital minerals that could bring healing to various ailments. But many years later when the tree was cut down, a pipe was exposed running through the ground and up the trunk. The “tree spring” was nothing more than a pipe coming up from a spring that had a tree forced to grow up around it, a man-made imitation meant to attract attention.

I am sometimes reminded of that tree spring as I see ideas and fads that make their way through education. They look refreshing and exciting. It seems that they will provide the answer to all the educational ills. Yet they end up failing because they are based on man-made facades instead of true wisdom and teaching. They will fade away because they are not true representations of Biblical education.

So where can we find the true springs of education? Jesus, who was called Rabbi, Master, or Teacher, gives several examples of educational principles that will never fail. In Mark 12, he says that the greatest commandment is to love God, quoting Deuteronomy 6. This passage in Deuteronomy also tells parents to teach their children God’s principles and always remind them of God’s Word. The first Biblical principle of education is that God’s word is the Truth that will never change; anything taught in schools or at home should be first based on the Bible. So educational trends such as teaching evolution or transgenderism, while they might look as if they are the solution to current problems, will eventually fall through.

A second principle that the Master Teacher Jesus shows is what content to teach his students. He met his audiences where they were, teaching and preaching with parables and stories that they could understand. His lessons met the specific needs of the people to whom he was speaking. Education based on Jesus’ style focuses on what the students will need to know for life on earth and eternity. Current classes (especially in colleges) that focus on unnecessary topics such as contemporary celebrities or entertainment will soon fade in popularity. And in K12 education, time spent unnecessarily on topics such as excessive testing or extensive focus on athletics takes away from the time that could be used to meet the children’s life needs.

Jesus as Rabbi also knew how to relate to His students. He was personable and relational—children wanted to sit on his lap—yet he provided discipline as needed. He called out sin in people and provided a framework of order. Contemporary educational fads that focus on a discipline-free classroom, teachers behaving as students’ friends, or administrators who are afraid to confront a child for misbehavior do not provide their students with boundaries they need to learn to respect authority and ultimately follow Christ. Christian educators should certainly build warm relationships with their students, but also guide them with proper authority and discipline.

So while the educational trends that flow out of modern philosophies look attractive and refreshing, they will not give the “true springs” that students need. A teacher rooted in God’s Word who provides educational content that his students need and leads the students down a disciplined path will make a difference for eternity.

In-Class Time-Out

As a teacher, I’ve always struggled to find suitable consequences for classroom misbehavior and have usually resorted to time off recess. However, overuse of missed recesses brings its own set of problems. Last summer one of my co-teachers introduced our staff to the Smart Classroom Management website and the books of Michael Linsin. Most of his practical advice was not new to me, but his method of in-class time-out became my standard consequence for classroom infractions.

This post is on how I carried out the time-out and its effectiveness for me. However, I want to make clear that the consequence is not what made it effective. Without the basic principles of having a plan, consistently sticking with the plan, communicating the plan, and calmly executing the plan, no consequence will be effective. Those are foundational to making any classroom management plan work well.

Reasons why I don’t find time off recess a good idea

- Students (and the teacher) need a break. Exercise helps stimulate the brain. Everyone functions better with periodic breaks.

- Supervision is an issue if you are responsible for students in two places at the same time. Students who are left in the classroom can get into more mischief. It’s also not wise to let students be unsupervised on the playground for long periods of time. And, depending on the age of the students, they need help getting their games started.

- The more times a student stays in, the less effective the consequence. For some students this becomes a habit, and it is just one more thing they don’t like about school.

- Keeping a student in at recess is sometimes necessary. You may need to talk with them or occasionally, missing recess will be the consequence that will make the student sit up and take notice.

Reasons for an in-class time-out

- It is a simple technique that the teacher subtly monitors.

- It allows students time to process and take responsibility for their actions.

- Even though students in time-out are not allowed to participate in class activities, the student will still have access to needed teaching and time to work.

- This method works best with lower elementary students (up to about fifth grade). Older students find it below their dignity.

Implementing the in-class time-out

There are steps to take to make an in-class time-out effective. It needs to be part of your classroom management plan. You need a place that is the time-out spot. You need to know what your expectations are for the student in time out. You need to let students know what you expect from them when they are in time out. You need to deliver the consequence with little fanfare or commotion. You need to be consistent.

Classroom management plan

- Keep it simple—just a few rules that cover a multitude of infractions. Here are mine from last year. Almost any classroom misdeed will fit under one of these rules.

- Listen and follow directions.