All Content

Cultivating a Servant Heart

Teaching is not merely the dispensing of information; teachers fill a place of authority. How will you exercise your authority? Anthony describes common abuses of authority and reminds us that authority is a tool to serve students effectively. In order to inhabit this servanthood authority effectively, says Anthony, we must bring our own God-given talents--and weaknesses--to bear.

Rabbit Traps

I am teaching phonics, covering a lesson where I just need to give information in a lecture format. There isn’t a learning activity to go with this piece of the lesson. The children are sitting quietly, but do not appear to be interested. In fact, I am getting bored myself! It is time for a Rabbit Trap!

I might stop in the middle of my lecture (we can finish it later) and announce, “Stand up! Take two giant steps to the north. Jump five times. Point to something that has a blend in its name.” We can then discuss the blends in ‘step’, ‘jump’, and whatever they are pointing to. Now we can continue with the lesson—we have been revived.

Rabbit traps? What are rabbit traps? Rabbit traps are those activities or experiences that capture the attention of the students and engage them in learning (Dr. Jean, 2014). As Professor Wood Smethurst says, “If you want to catch a rabbit, you have to have a rabbit trap” (qtd. in Dr. Jean, 2014). We need a variety of rabbit traps to catch the variety of students. Different “rabbit traps” will attract different students.

So what can we use as rabbit traps? We can play learning games, such as "Around the World" or board races. We might play a quick game of "Simon Says." Songs with actions, motions, or movement are rabbit traps. We can sing songs for phonics or math. We could sing the days of the week. We might do rhymes or action poems. Five Little Monkeys Jumping on the Bed” is a good song for subtraction. “Hickory, Dickory Dock” is nice for telling time. Puppets, objects, props, and manipulatives are rabbit traps. A puppet can check the handwriting pages. Actual items such as starfish, shells, rocks, old coins, arrowheads, or a stuffed animal will capture attention. Use props, such as a colorful piece of cloth for Joseph’s coat, furry fabric for Esau’s skin, goldfish crackers and bagel chips for the five loaves and two fish, or Nilla Wafers for manna.

A mystery object (something the children must guess what it is) or an object hidden in a bag can be a rabbit trap. Interesting sounds (find online, or make your own) can grab the attention. Turning off the lights, whispering, or doing something unexpected, such as suddenly saying, “Stand up!” or asking for some quick exercises can be rabbit traps. Another rabbit trap is hiding surprise cards within the pack of flashcards. These may be cards with quick brain breaks, such as “You may get a drink”, “Shake hands with a neighbor,” or an unrelated item, as a reading word in the middle of the math flashcards.

Rabbit traps help the teacher, too. These traps keep me engaged and are fun to plan to surprise the students and help them stay motivated.

Real rabbits have been feasting on my dad’s green beans. It is annoying to find sections of the rows that are eaten nearly to the ground. It is difficult to trap a real rabbit: Why would they want to go after the bait in a live trap when they have a whole garden to enjoy? One must plan carefully what kind of bait to use in the live trap. Just so, it may be difficult to “trap” the attention of the students at times. We need to know our students well so we can use good rabbit traps. We can plan for those “rabbit traps” to snare their attention and keep them motivated and learning.

Source cited: https://drjeanandfriends.blogspot.com/2014/05/if-you-want-to-catch-rabbit.html

Photo by Gary Bendig on Unsplash.

How I Use a Token System for Classroom Management

When I first heard other teachers talking about using a token economy system in their classroom, I thought it sounded far too complicated. I was fine with simpler methods of management, and a token system just sounded like more work, which I certainly didn’t need. Over the years, however, I gave it more thought, and eventually I heard enough about the perks of this system that I decided to give it a try. I have used a token economy in my third-grade classroom for six years now, and the fact that I continue to use it shows that it has worked well for me.

Before I describe this system further, let me offer a few caveats. First of all, I don’t particularly like the word system. It is important to remember that your number one classroom management tool is a caring relationship with your students. No perfect system exists, and because you are working with human beings, every management technique has its flaws and exceptions. Systems have no power to change hearts. Also, please don’t hear me saying that I think this is the only way or even the best way of doing things. Different procedures work well for different people, and you need to find what works best for you.

With those cautions in mind, I will tell you how I use the token system in my classroom. I post a chart on the wall with the names of all my students and five smiley faces beside each name, one for each day of the school week. When a student breaks a basic classroom rule or procedure, such as talking without permission, I take down his or her smiley face for that day. A second offense on the same day brings some other consequence, but with most students this rarely happens.

At the end of each week, every student gets the same number of tokens as the number of smiley faces that are left beside their name. The tokens I give them are simply laminated squares with a printed picture that fits with our classroom theme. The students are responsible for keeping these in a safe place. They also have the occasional opportunity to earn additional tokens for doing good work, keeping a neat desk, etc. At the end of every month, we have Token Store, and the students are allowed to spend the tokens they have saved up to “buy” small rewards.

One of the things I like best about this system is that the tokens basically establish a classroom currency, which can be used in all sorts of ways. One way I use it is to have students pay “fines” for some things. This is nice for using as a relatively benign penalty, especially for those students who are extremely sensitive and would be devastated to lose a smiley face beside their name on the wall chart. For instance, if someone needs to go to the back of the room to get their homework from their backpack because they forgot to unpack it before school started, they need to pay a token as a fine. Simple forgetfulness can happen to anyone (it is not deliberate disobedience), so I hate to make a big deal of it. Paying a token is no big deal, and yet it is a great motivator to help students remember to unpack their backpacks before school next time.

Another way that I use tokens is to help raise awareness of being responsible for classroom tools and materials. I give my students some things at the beginning of the year (scissors, glue, etc.), and parents at our school are sent a shopping list of things their students should bring on the first day of school. I tell my students that they are responsible to take care of their tools and to keep from losing them. Of course, they always have the option of asking their parents to buy them new things, but if we are in the middle of class and a student does not have a necessary item (such as a pencil) because they lost or broke theirs, they need to pay tokens to buy a new one. As adults, we learn quickly that it hurts us economically if we are constantly losing or breaking our tools. Schoolchildren are not too young to start learning this principle.

I love that this system also helps students to practice some basic math skills: If I have twenty-five tokens saved up, do I have enough to buy these two items that each cost fifteen tokens at Token Store? Likewise, it can help them think through saving versus immediate gratification. Most of the things I have available for students to buy at Token Store cost less than a month’s worth of tokens, but I intentionally keep a few larger items that require them to save tokens for several months if they want to buy them.

My students always look forward to Token Store, and I enjoy the excitement and positive atmosphere it generates. Children can be enthralled by simple things, and I’m often somewhat amused at how much joy it brings them to go to the “store” and buy a fun eraser, a lollipop, or some sparkly stickers.

Is this system complicated? Perhaps in some ways it is, but it also simplifies some things. For me, the benefits outweigh any extra work or inconvenience that it causes.

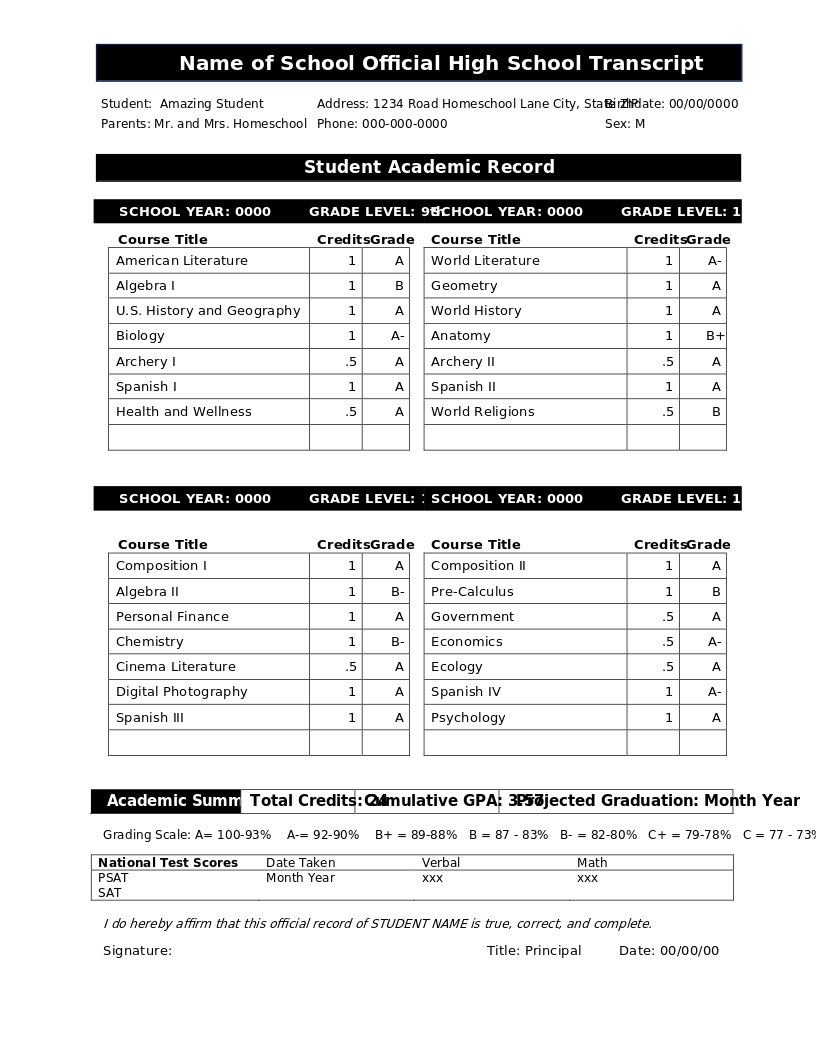

Mathematics: Studying God's Greatness

Why study math? This document presents concepts students may not have contemplated. Math points us to the greatness of our Creator. Studying arithmetic, geometry, algebra, and calculus can help us to more deeply appreciate the greatness of our Lord. Although the document discusses calculus, no prior knowledge of calculus is assumed.

A Beginner's Myths, Part Two

We continue our look at a few myths teachers can buy in to.

Myth: Last year we could… I’ve seen unsure beginning teachers fall into the trap of allowing students to dictate how the classroom should be run. Students will say, “We’ve always been able to do…” or “Other years we got to…”. Most times these comments are to the advantage of the student. But just because a student says it, doesn’t necessarily mean it was so. Students rarely see the big picture. For them, “always” may really have been not often. They also do not see the times the teacher realizes that what is happening is not what she wants to see. If a student challenges your method of classroom management because “that’s not how we do it” or wonders when you will go on a hike because “they always go in October”; don’t make decisions you are unsure of until you’ve checked further. The students may have a valid point, but they may not. If you aren’t sure, a good response is “I’ll check into it.”

A real-life example that I witnessed some years back: Our school policy manual states that students should walk quietly in single file when in the hall as a group. We had several years of loose structure in the junior high classroom and this procedure was not followed as it should have been. Then we got a new teacher. In their ignorance, they allowed the students to persuade them that the junior high didn’t have to follow that procedure since they “never” did before. Thankfully, the teacher realized their mistake and let the students know that the procedure was for everyone.

Myth: Last year’s teacher didn’t do a good job teaching the material, or it must be that I’ve been handed a group of slow learners. That may be correct. However, it is more likely that students are just rusty after several months of vacation. Second and third graders, especially, can find a new school year challenging. Be prepared to spend the first couple of weeks reviewing. Within a few weeks, everyone should be back where you want them to be.

Myth: School should be fun. A statement from the student teachers’ goals for teaching said, “I would want to make school fun for the students.” School should be interesting and enjoyable—school is not meant to be fun. If school is to prepare students for life, it should mimic life. Life is made up of struggle, hard-work, decision making, service, and daily monotony. A redeemed life well-lived is joyful, not pleasure-filled. School should be interesting—help students find interest in Bible truths, intricate math and science designs, the stories of history, and the enjoyment of poetry or prose. Projects and experiences help build interest. Students will find enjoyment in hard work and accomplishment. Teachers do not need to constantly provide parties, treasure chests, and extra recesses to make school fun. Too much of a “good” thing turns it sour. Student mentality easily slips into entitlement. Does that mean that a teacher should never treat her students? No, a few treats to look forward to can be a good thing. Doing a few special things in the midst of February’s winter days can brighten the atmosphere. But all the fun things in the world will not bring the satisfaction that successfully working through the struggle and hard tasks of the school year can. We should not do fun things for the sake of fun things lest “…in the last days…men shall be lovers of their own selves…lovers of pleasures more than lovers of God” (2 Timothy 3:1-2, 4).

Myth: The teacher’s worth is determined by how her students feel about her. It is easy to gauge our worth as a teacher by how well liked we are by the students and how much praise comes from the parents. A “you’re the best teacher ever” or “our children are enjoying school more this year than ever” comment can send us soaring to Cloud Nine. And three months later “you never let us do anything fun” and “why are you so hard on Johnny for whispering” from the same lips can send us into despair. Our worth is not determined by what our students think of us. Our worth is determined by what God thinks of us.

If our goal is to please God, we can rise above the complements and critiques. That is not to say that complements and criticism have no place in how we evaluate our teaching. It is well to consider what others have to say about us. But a teacher cannot stay the course if they are only trying to stay on the good side of the students.

Blessed is the teacher who can discuss ideas and frustrations with an experienced mentor. If one has never taught before, stepping into the teacher shoes carries with it a lot of uncertainties and questions. Being able to ask someone with experience is very valuable.

A Beginner's Myths, Part One

New teachers want their students to like them and to enjoy school. New teachers do not always know the best way to accomplish this. Older teachers can also find themselves buying into the following myths.

Myth: I’m capable of handling this on my own. A teacher does need to take ownership of her classroom and students. But none of us can be immediately successful of ourselves. Of greatest importance, we need to recognize that without the help of God we are nothing. We need His wisdom and aid every day. We also need advice and help from other teachers, the principal, the board, and the parents. They cannot do our work, but they can shape the way we do the work.

Myth: If I show enough love for my students, they will love me, and I won’t have to discipline them. There is a kernel of truth in this statement. The teacher who truly loves her students fosters respect for herself and the student, making discipline much easier to administer and be received. However, the teacher who overlooks misdeeds or gives in to student demands because she wants her students to know she “loves” them, does not truly love her students. True love for students will seek ways to for those students to grow in character. Many times, character growth involves some form of discipline whether self or otherwise imposed. Truly loving our students will give them the direction they need, even if we shrink from that need. Most of us do not enjoy correcting other people’s children; but “love” alone will not build character.

Myth: A teacher needs to carry a big stick. This myth is the opposite of the last one. Yes, a teacher must be the one in charge of the classroom. But you can be in charge without being heavy-handed with it. Students do like to know where the line is drawn. If they don’t, most will keep pushing until they find it. Communicate with the students. Make your expectations clear. Make sure the students understand what you want. But don’t get into a power struggle with them. Project matter-of-fact confidence that they will do as you expect. And then if they don’t, handle it confidently without making it big deal.

Many times, a look can quietly take care of disruptions without distracting others. An illustration: In the cafeteria one day a mischievous second grader was testing his teacher’s authority. Her pleading words were just part of the game for him. I happened to walk past and instinctively gave him a raised eyebrow look that he knew from the previous year. He wilted and turned to do what his teacher told him. She didn’t know what had transpired, but I realized after I’d passed that I’d been interfering with her actions. I did find it an interesting study of a student recognizing someone in control.

Don’t show frustration or anger. A calmly stated command, “Please go to your seat,” is more effective than a raging torrent of words. A teacher does well to remember to apply the least amount of energy that it takes to solve the problem. Most times the less words used the better. The big stick often causes resentment. How do I know? Even after many years, I sometimes still forget and ruin all that had been accomplished beforehand by wielding the big stick.

Myth: You can’t smile till November. A student wants to know that their teacher wants them in the classroom. Kindness and empathy are important assets of a successful teacher. Genuine smiles and words of appreciation let a child know we are aware of them, and we want them to succeed. We all need encouragement to do our best. Positive feedback gives us the will to keep working. A teacher’s genuine praise builds trust and teamwork. Letting our displeasure or grouchiness habitually show breaks down respect for the teacher and creates an atmosphere of discouragement. This does not mean that we don’t deal with less than perfect issues. We just do so in an honest and kind way.

Myth: Students coming back to school need a few days of grace to learn what your expectations will be. There is truth in this statement. However, it is a myth to think that you will not need to enforce expectations for the first few days. In this way, you lose valuable ground in developing your classroom management strategies.

Students do need time to practice and have reinforced the way you want things to run in your classroom. Spend time every day for the first while reviewing and practicing expectations. However, students are also going to want to know that they can depend on you for consequences. Don’t let them down. Students will also forget the first while. Consequences will help them remember.

For first grade students, I may not introduce the consequences in full detail on the first day. They already have much new material cluttering their minds. I do introduce a modified version and as time goes on continue to add details as needed.

Example: Beginners need to learn to raise their hands for permission to talk. This is a new habit they need to make. I introduce the idea, model it, and get them to practice. We review several times during the day—maybe after breaks or other free time activities. I have a list of the student names on my board. If a student forgets I remind them and put a mark after their name. We may also practice raising our hands again. This mark is the only consequence at this time, but we turn it into a game of trying to keep the marks off the board. Those first few days, I will usually comment on students who have no marks and then erase them all several times a day—after lunch, after recess, etc. Every day I lengthen the period the marks stay up until I no longer erase them at all. I usually recognize students who can make it through the period or day with no infractions. As I need to, I will introduce the next steps of my consequence plan. Some years, I need to do this within the first two weeks. Last year, we were in the fourth quarter until it become necessary to fully implement the plan.

We have a fairly consistent classroom management foundation for elementary. Each teacher adapts it to fit their style and group of students but most students beyond first grade have an idea of what is expected of them. Teachers who introduce their plan and reinforce it through review, modeling, practice, find that providing consequences, if necessary, the first day lay a good foundation for the rest of the year.

Part 2 of this series will address a few more myths teachers may encounter.

Fostering Internal Motivation

Justin looks over the math problem, pondering how to solve it. “If I multiply these two numbers, and then add this number, I think I can find the surface area,” he ponders. “Yes, it works!” he grins, and looks up at the teacher with a satisfied expression. He has worked through the problem on his own and has come up with a satisfactory conclusion.

Recently I was discussing with a group of seasoned teachers from Christian schools the changes we had seen in education over the last twenty-five years. One difference we all saw was the gradual decline in students’ internal motivation for excellence. Perhaps we were showing the “good-old-days” syndrome where we didn’t remember accurately, but we all agreed that students seem much more willing to settle for mediocrity now than before. And certainly, we agreed, students require much more spurring from the teacher to complete assignments, especially if the assignments are not entertaining. What had caused this, we wondered. Was it because COVID had interrupted the education of these students, reducing the value of education in their minds? Was it because so much of children’s worlds today are based on entertainment? Was it because we teachers needed to change teaching methods to match current students?

Educational researcher Anna Schwan recognizes that “assessing and measuring motivation is difficult because it is an internal function, and assessing an individual's motivational state relies on observable behaviors or directly asking” (1). But by observation, teachers recognize that motivated students show interest and effort and are willing to try new things while unmotivated students lack direction and are detached from the learning environment.

So how do we move students from the unmotivated to the self-motivated stage? Here are some intellectual and hands-on practices to encourage your students in self-motivation.

Philosophical methods of encouraging student self-motivation

- Schwan says, “Before any attempts to understand motivation or respond to motivation, educators must develop meaningful relationships with their students” (4). These relationships allow the teacher to base things on what students are actually interested in and also to recognize why there may be at times a lack of motivation. If you know that Cherice loves kittens, you can add numbers of kittens together in your sample math problem. Or on a more serious note, if you know that Jason’s parents are struggling at home, you can have sympathy with him rather than being annoyed when his eyes glaze over instead of focusing on his reading assignment. Students react positively to a teacher they know cares about them, thus increasing their desire to learn in that teacher’s classroom.

- Schwan also suggests teachers should help students to understand why what they are learning matters and how they can use it in the future (4). To do this, the teacher can create real-life learning experiences. So when teaching formulas in algebra class, you can do a sample problem that figures the amount of feed needed for Calvin’s cattle. Or when dividing fractions, you can bring measuring cups and make half a batch of chocolate chip cookies. When students see that what they are learning actually matters in real life, they will be motivated to prepare for their future now.

- Another way to increase student motivation is for the teachers to model enthusiasm for what they are teaching. If the students know that the teacher cares, they are more apt to care. And enthusiasm is contagious. On a recent student survey at the end of a college class I taught, one of my lower scores was for “enthusiasm over subject taught.” Now granted, this was an early morning class in the winter, and class started when it was still dark out. But I really was excited about the class even though I evidently didn’t show it. I made a concentrated effort to demonstrate my enthusiasm in the next class, by sharing what I liked about the content discussed and by varying my vocal presentation.

- Teachers can also prompt students to be self-motivated by helping them set high yet achievable goals. When students are a part of setting the goals, they feel included in the need to reach them. They should also track their progress to those goals and self-reflect on their efforts. For example, when writing an essay, the teacher can meet individually with each student to go over the rough draft. Together, the teacher and student can determine what needs to be changed for the final draft. Then with the final draft, the student can include a sentence or two explaining how he or she met the goal.

- A fifth way of teachers helping students be self-motivated comes from encouraging personal satisfaction upon reaching the goal. While we don’t want to build pride, it is acceptable for students to acknowledge that they achieved their objective and to feel glad about that. Teachers should praise students for meeting their goals. Intrinsic motivation is fed by recognizing that growth is attainable.

Quick, practical ways to build student self-motivation

- Teachers often fall back on extrinsic or outside prompts for the classes that are difficult to motivate. And sometimes this is helpful and necessary. So add a kernel of popcorn to the jar each class period that the class is quiet; then have a popcorn party when the jar is full. But be careful not to make the goal too easy and not to depend solely on rewards for motivation. Once habits and patterns are developed, extrinsic rewards can fade into intrinsic rewards (although there is nothing wrong with rewarding small prizes for goals achieved).

- Another method of increasing self-motivation in students is to offer different types of experiences. Hands-on activities such as making homemade ice cream in a ziplock bag for science class, field trips to local museums, guest speakers from your church who can tell about their career–these offer variety for the student who is not as interested in traditional classroom lessons. Parents are a great resource for this, as many are willing to do a craft activity or science experiment, particularly if the lesson is about an area of their expertise.

- Teachers can also encourage student motivation by making things fun—but also explaining that not everything in life is fun. Games, projects, and crafts are all appropriate ways to increase the “fun-ness” in the classroom. A little friendly competition also builds students’ participation. But sometimes basic reading and writing assignments are acceptable and even the best method of teaching.

- A final quick way to increase self-motivation is to encourage students to focus on their interests when they have a choice of topic (and give them a choice whenever possible). When I had just started teaching, I had a student choose to study and give a speech on roses. She didn’t care about flowers, knew nothing about them, and was obviously bored with the entire project. As a more seasoned teacher, I would have told her to change her topic to one that interested her. Then her interest would have prompted her learning.

Works Cited Schwan, Anna. “Perceptions of Student Motivation and Amotivation.” Clearing House, vol. 94, no. 2, Mar. 2021, pp. 76-82. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00098655.2020.1867490.

Why Everyone Gets to Hit and Make it to First

I have a few fond memories of my elementary school physical education days: the time we filled a real parachute with ping-pong balls, stood around it in a huge circle, held on to the edges, and shook it up and down in giant waves until every single last ping-pong ball had escaped onto the playground. I remember enthusiastically square dancing, jumping rope, and trying to keep a blown-up balloon in the air for as long as we could.

But I can honestly say that the most scarring event in my elementary school career was having to play kickball. I absolutely abhorred those kickball games. Here’s why.

No one had ever taught me how to kick or catch the ball, and I didn’t know the rules. I was absolutely frightened of the ball and the game; and I was terrible at it. To make matters worse, the other children loved kickball and it was evidently really easy for the teachers to just let us pick teams and play. Which brings us to another damaging aspect of the game: choosing teams. Two of the more aggressive, athletic boys would deem themselves captains, usually with the approval of the other students. (I’m not sure what the supervising teachers were doing at this point since we didn’t have smartphones back then.) Then we all lined up, and one by one, the players were chosen, from the best down to the worst. And guess who was almost always chosen last? Me.

So, after several failed attempts, most of which included a lame kick which inevitably missed the ball altogether, and possibly one or two attempts where my foot actually made contact with the ball but didn’t go anywhere, I was easily gotten out by said ball being thrown at my body or to first base long before I made it there. I was always an easy out. The frustration, annoyance, and disdain I felt from my peers was devastating. I made good grades. I never laughed at their bad poetry or terrible art projects. It seems like playing sports was the only time that students could be openly humiliated.

Then I discovered THE SOLUTION.

THE SOLUTION was actually incredibly easy. When my team was in the outfield, I got so far away from the diamond that I rarely, if ever, had to touch the stupid ball. When it was our turn to kick, I made sure that I was the last in line. I rarely actually made it up to the front of the line where I’d have to kick, but if I even got close, I’d ask the teacher if I could go to the bathroom. I was never denied. I would take a leisurely walk to the bathroom, and by the time I had returned, my team was always back in the outfield. Problem solved. Except I still felt chagrin every time teams were chosen, and I developed a strong distaste for sports. Thankfully, God created elementary school children with some resilience. But I decided two things back then:

- I really hated kickball, or any kind of balls, and just about any sport because of the horrible experiences I’d had.

- If I were ever a teacher, my students would NEVER have to endure the kind of humiliation and shame that I had for several years.

Fast forward fifty years. Okay, a little more than that, but it’s close enough.

Now I am a teacher, and after fourteen years of refusing to teach physical education, I am the P.E. teacher. (Seriously. I once told the principal at an interview that I’d teach anything except P.E. He laughed, thinking I was joking. I assured him I was not.) So, I made three more decisions.

First, my students would be well-rounded. Besides learning how to play basketball, softball, tennis, and kickball, they would also take nature walks, fly kites, play croquet and badminton so that everyone would get to experience some type of physical activity that they actually enjoyed, and not have to play the ones they didn’t like (a.k.a. kickball) too often (which for me was just about every single P.E. class or recess except for the times the teachers found the parachute, jump ropes, or square dance record. Yes, record. I already dated myself to being in school in the 1960s, so it really doesn’t matter if I mention that now.)

Second, when we did play sports involving (cringe) balls, my students would be instructed and coached, ever so gently, how to correctly hit or catch the things.

Third, and most importantly, every single child from kindergarten up to whatever the oldest student was, would have a chance to hit the ball and run to first base in a positive, encouraging environment, without someone purposefully getting them out as quickly as possible, especially when they were just learning.

Sometimes that means standing ten feet away and pitching an unbelievably slow underhand pitch with a large, soft, bright yellow ball. Sometimes that means that the students get ten or fifteen tries before they hit the ball and run. That’s okay. They are learning the sport, having the opportunity to be physically active, and most importantly, they are working together, cheering each other on, and learning how to treat their fellow students in a kind way. All of this is done in a very non-threatening and encouraging environment. Everyone cheers when a kindergartener hits the ball. We all yell, “Run, run!” while he valiantly dashes for first base, with sixth and seventh graders purposely fumbling the ball and taking their time before they throw it to first base.

Everyone gets a hit.

Everyone makes it to first base.

And everyone certainly seems to have a positive attitude toward sports because of the way they have been treated by their fellow students and because of the way it has been approached.

Everyone feels comfortable trying to do their best in an encouraging, non-threatening environment. That is more important than having students shamed, embarrassed, and humiliated just because of a silly ball. Here are a few steps to take so that your non-athletic students can appreciate and enjoy sports.

How to Gently Initiate Students into Sports

- Teach correct stance and foot position.

- Teach how to hold the piece of equipment (hand position, etc.).

- Teach how to swing or kick in slow motion. If involving a bat, this includes how to slowly and gently set the thing down before running. I’ve known several people who had to have back surgeries, face surgeries, and lots of dental work because of this issue. By the way, I was never teaching when these things happened. I was either a frightened student staying so far away that I could barely tell who was batting, or back inside the school building looking for papers that needed to be graded—or the restroom.

- Teach the rules of the game. This not only includes saying the rules, but also acting them out, again, in slow motion, with no stress. At our school, I give the instructions, then we all practice doing it, one step at a time.

I practice these rules for every sport, and my students not only know how to play softball, basketball, and tennis, but also how to be patient and kind with their fellow students. That’s gold!

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

A Prayer for the End of the School Year

Our Father, our God of peace and power,

Give us strength for the ending of this school year.

You have led us, guided us, and cared for us. You have been our source of joy, love, and wisdom. You have loved us with a love beyond comprehension.

We have experienced no good apart from You.

Thank You.

Thank You for enabling us to do Your work this year. Thank You for strengthening us when we had nothing left to give. Thank You for Your Spirit’s leading in difficult moments and uncomfortable conversations. Thank You for inspiring us when our own wells of creativity were dry. Thank You for the incredible gift of Your presence in every moment of every day.

We could not have done this without You.

Help us to reflect on this year accurately, not with an inflated or deflated view of our experience.

For the moments of victory and accomplishment . . . give us humility and gratitude.

For the times we failed and fell short . . . give us assurance of your forgiveness.

For the unresolved messiness that we can’t make sense of . . . give us trust in Your redemption.

For the words we wish we could take back . . . give us peace.

For the memories that make us smile . . . give us delight in Your good gifts.

For the lessons we learned along the way . . . give us strong memories and the courage to move forward with new knowledge.

We ask you to take our efforts and multiply them. May every lesson plan, every hour of preparation, every graded paper, and every piece of content taught be a small part of building Your kingdom.

We release our students fully to Your care. Help us to trust Your good work in their lives. When our hearts feel heavy for the students we wish we could have helped more, the ones whose stories live in our hearts, the ones who we struggled to understand, or the ones who are existing in spaces that are not safe emotionally or physically—give us an assurance that You love them more deeply than we ever could.

We open ourselves to You as we enter the in-between world of summertime. Help us to trust Your good work in our own lives. When we feel strangely untethered and empty, when we long for routine and familiarity, when we settle into spaces of rest and relaxation, when we miss our students and when we definitely do not—give us grace to live well.

Thank You for what You have done, thank You for what You are doing, and thank You for what You will do.

Amen.

School Year Reflections

How was your school year? Do you feel exhausted but exhilarated, like a mountain climber who has just reached the summit? Or maybe you feel energized, already excited as you look ahead at another school year. Perhaps you feel like a survivor who has finally been released from a harrowing ordeal. I just completed my seventeenth year as a teacher, and I have experienced all of the above at the conclusion of some school years, as well as a kaleidoscope of other feelings. Every year is different, with its own set of challenges and unique situations.

This school year was a bit topsy-turvy for me. Our school began on a somber note, since the father of one of our students died in a small plane crash shortly before the beginning of the school year. So after only three days of school, we took a day off for the funeral.

Then too, I had a student with some anxiety issues that caused him to miss one or two days of school every week for most of the first quarter. Around the time that he finally started coming to school regularly, another student landed in the hospital with complications from chicken pox. Soon she was on a ventilator, fighting for her life. I realized that I had no experience in guiding my students through the reality of a classmate’s life-threatening illness, and I struggled to know how to talk about it with them. How we prayed!

Thank God, that student did recover, but in the process, she missed more than a whole quarter of school. I was at a loss to know how to reintegrate her into the classroom. Besides this, multiple other students missed multiple days of school. Not one of my eighteen students had perfect attendance. All told, I spent much of my school year trying to help students catch up on missed work.

You never know what a school year will throw at you, and flexibility is the name of our game. While it is impossible to be prepared for every obstacle, it is possible to learn from adversity and to find the good things that stemmed from it. This year I saw my students develop compassion, sensitivity to spiritual things, willingness to help others, a strengthened faith in the power of prayer, and other traits that may have been aided in part by the circumstances that I certainly would not have chosen.

As we reflect on the school year, it is good to evaluate: What went well? What could I have done better? How will I change things next year? How can I learn from my mistakes? How can I use the experiences of this school year to make me not only a better teacher but a better person? If you look back on the school year with a sense of failure for the mistakes you made, may you experience grace. Refuse to dwell on the past, and instead look forward with determination to meet the next challenge well and to get up every time you fall. Be like my student who spent weeks in the hospital last fall: In December, she was relearning how to walk. Five months later, we clapped and cheered as she crossed the finish line to complete the mile run on our school’s track and field day.

Photo by Michael Skok on Unsplash

Must-Reads Book List

The compilers chose for this list books recognized as timeless classics, or books that form values or expand the minds of readers. Books listed in the preschool through lower elementary sections can be enjoyed again and again. Many children read and enjoy the books listed before the suggested grade level.

If authors are starred (*), all or most of their books are recommended.

Recognizing that choices of reading materials vary from family to family, these compilers do not endorse all the content in every book on this list. Teachers, parents, and communities will need to exercise discretion.

Download the list or preview it below.

Notes to the Younger Me

Our school year is over. The report cards are filled out the last time and the permanent records are back in the file cabinet. The seniors have graduated, and we’ve had our last day of school celebration. The classroom has its summer look: semi-bare walls, empty desks, filed flashcards, and pulled window blinds. Everyone is ready to enjoy summer break.

But while finishing the last tasks of this year, I found myself reflecting on my early years of teaching. Here are a few things I would like to tell my younger self.

- Don’t be too shy, hesitant, insecure, or proud to ask questions of more experienced teachers. It’s okay to not know all the answers already. And even though you think your ideas are as good or maybe even better than the previous teachers, ask anyway. There may be reasons for doing things that you don’t know about.

- Remember that little boys are energetic, boisterous, and loud by nature. They are not trying to be bad. Yes, they need to learn to sit properly, walk in the halls, and leave the roughhousing for outside of school. But just because they forget, doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t want to obey. Sometimes you need to help them remember. But don’t think that every time they forget it is because they are just rebellious.

- Young students need lots of practice, drill, and review and more practice, drill, and review. Few students remember to use capital letters and punctuation without practice. Math facts do not stick in minds without understanding and repetition. Reading takes practice, practice, and more practice until it becomes automated.

- You cannot solve all your students’ problems. Your responsibility is to the students during the hours they are at school. You are responsible for their academic learning and their social life at school. Yes, you can and should provide a haven during the six hours they are in your care, and teachers do influence their students. However, we cannot be the savior of every child we teach—that’s not our responsibility.

- Don’t take things too personally. A disrespectful, disgruntled, or disobedient student is not necessarily acting against you as a person but against the authority you represent. The parent who chews you out may be acting from their own frustration of being in a no-win situation-especially if it concerns misbehavior on the part of their child.

- Be clear in your expectations. Tell, show, demonstrate, and practice how you want things done. Make sure students know what you expect. Then expect students to carry through.

- Kindness and consistency go a long way in creating a happy classroom.

- Parties, treats, and rewards are not what make students do what you ask them to. They can add spice and energy to the school year but do not expect rewards to do your job.

- Don’t say things you don’t mean. Don’t threaten punishment if you aren’t prepared to follow through. In like manner, don’t make promises you can’t keep.

- Keep goals for yourself and your students attainable. Stretch a little but don’t stretch so much that one gives up.

- Success begats success. Hard work never hurts anyone, but hard work with no success is discouraging. Success is, in itself, a reward for the hard work.

- Teaching school is work, sometimes very hard work. It is not a job you do by yourself. You need the help of those around you: your co-teachers, the parents, your board, and the principal. But most importantly you need the help and wisdom of God.

I would also like to tell my younger self that teaching brings joy, laughter, delight, appreciation, sighs, disappointment, tears, and frustration. It holds something that brings me back year after year. But for now, I’m going to enjoy the summer months.

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Do the Write Thing, Part 4: Engaging with Reluctant Writers

It’s every writing teacher’s dream: the classroom is quiet except for the scratch of pencils flying across paper and the gentle tick of the clock in the background. You can almost hear the gears of creativity and productivity turning brilliantly in each student’s mind. It’s perfect, except . . .

There always has to be an “except,” doesn’t there?

Except for that one student, whose mind seems to be one big blank. The minutes tick by, and no matter what you do to help him, he can’t manage to write a single word. He just stares at the blank page all class long.

You can’t help but wonder: what’s wrong with him? What’s keeping him from being able to do what every other student in the classroom seems capable of doing? And more importantly, how can you help him?

If you’re hoping for easy answers, with a nice three step formula to make it all better, unfortunately, you’re going to be disappointed. Like most things in teaching, the answers are not simple or one-size-fits all. But, that being said, there are some tools you can add to your tool belt that can help your students become more confident and successful in their writing.

One huge issue facing children as they write is simply the neurological difficulty of the task. Writing is hard work for anyone, but especially for children.

Think about all the parts of the brain that need to be working in order for a child to write a story. They are using the motor areas that help them to physically hold a pencil and form words on the page, activating the part of the brain that stores spelling and grammar rules, planning ahead and making decisions, generating creative ideas, concentrating on the task at hand, imagining and visualizing what they’re creating, retrieving facts or memories from long-term storage, and putting thoughts into words through the language production center.

Neurologically speaking, writing is one of the most complex tasks you will ask your students to do. If you can cut back on how many mental tasks students need to do at once, writing can become easier for them.

For some students, the physical act of handwriting uses a disproportionate amount of their mental energy, leaving little left for the other neurological aspects of writing. If you require students to write in cursive, consider lifting that rule for writing class. Allow students use whatever handwriting method is easier for them (or allow typing or talk-to-text, if you have those options available).

Another mental block that can impede students’ flow of writing is getting fixated on grammar or spelling. A simple way to eliminate this problem is to make a policy that students are not allowed to ask questions about spelling or grammar while writing. Some students put so much energy into thinking about how to spell what they’re writing that they have no energy left for the actual writing.

If a student asks how to spell something, you can just say, “Sound it out for now. You’ll know what you mean, and we can fix it later.”

You may feel as though teachers ought to be insisting on correct grammar and spelling at all times. Won’t it give your students sloppy habits if you don’t require them to write correctly?

However, that’s what editing and revising is for. While writing a rough draft, students’ main priority should be their flow of writing. Freeing up the mental space of their inner editor is one way you can prioritize their brain power for the actual writing quality.

Planning and generating ideas are two more brain faculties needed for writing. If you guide your students through brainstorming activities before they write, they don’t need to both plan and write simultaneously. This can help to reduce the number of tasks they need to do all at once.

Concentration is another neurological task that we can help make easier for our students. One way is to create privacy cubicles from file folders taped together or several opened textbooks.

Another great way to focus students’ minds is to play instrumental music while they’re writing. Studies have shown that for many people, background music is effective at focusing their creative energy. It’s important that it has no words and that students choose to not let it be an extra distraction. But soft classical music can boost creativity, with the added bonus of lending a lovely atmosphere to a writing class.

Struggles with imagination or visualization can also create great difficulty in writing. This is likely what’s happening if you have a student who has run out of words after half a page and looks at you with desperation in their eyes when you ask them to try to write a little more. These students will struggle to come up with creative ideas or any ideas at all.

It’s important to remember that when it comes to creative output, there will be a wide range of abilities in your classroom. That is normal and okay. However, there are some things you can do to help students who struggle with creativity.

One really great way is to read what they have, which is likely bare-bones and skimpy on details, and then ask them lots of questions. So if they have the sentence, “The man walked into the house,” ask them questions and help them to add details. What was the man’s name? Is he tall or short? What colour is his hair? How old is he? What’s he wearing? After you have helped the student build a mental picture of the man, encourage them to write several more sentences about him, adding those new details.

Then you can move on to the words “walked” and “house,” asking them more questions and encouraging them to add more details based on their answers.

Another variation of this process is have the student draw a picture of the man walking into the house, then write sentences to describe the picture. Sometimes just changing the mode of their imagination to visual can help to break down some of those mental barriers.

When simple changes are made to simplify how much mental energy is being used on various neurological tasks, it frees students’ brains to focus on fewer things. All those little things can be a big thing when it comes to helping your students to write confidently and competently.

Sometimes, however, a student’s issues with writing are not related to the difficulty of the neurological process but are tied to fear and perfectionism. The fear of the blank page can be absolutely overwhelming to some children, which is often due to the mistaken idea that what they put on the page needs to be perfect. They have this idea that once they’ve written something down, it can’t be changed. And that creates this incredible pressure to get it right.

It is easy to unintentionally reinforce this mindset. So watch how you talk about a rough draft. If you create an atmosphere of dotting every “i” and crossing every “t” properly in a rough draft, it can communicate that you expect perfection. Again, the simple practice of not worrying about grammar, spelling, or perfect handwriting can help students take the pressure off themselves in a first draft.

Since it is so easy to accidentally communicate that first drafts need to be perfect, it takes intentionality to reverse that. Some teachers refer to rough drafts as a “sloppy copy” or a “messy draft.” That kind of language clearly communicates that rough drafts are supposed to be messy—and by extension, imperfect.

Another way to create a writing class culture that chips away at this paralyzing need to perform is to focus on revision after writing. When students get used to spending significant time revising their work after they’ve written it, they will put much less pressure on themselves while they’re writing it.

One other thing you can try for a child who can’t overcome the big bad blank page is simply folding their paper in half or in thirds. It’s such a simple thing, but sometimes that can be all it takes to get them over that hurdle.

Students’ fear of the blank page, often caused by perfectionism, can take time to overcome. However, the freedom they can find is well worth the time and energy it takes.

None of these strategies are miracle fixes. But with these tools at your disposal, hopefully you can work with your reluctant writers to turn them into confident communicators. And maybe, someday, you’ll have that idyllic writing class—with no “excepts” in sight.

The Selfless Teacher

Patiently waiting for a first grader to painstakingly sound out a word, resisting the urge to help him out or correct him, and then relishing in the moment when he pronounces it correctly—this isn’t something most people can easily do.

Noticing months later how much a student's handwriting, spelling skills, or history grades have improved is another reward bestowed upon only the patient, the enduring, the brave—the teachers.

Waiting until my students have understood and absorbed a concept before taking a restroom break myself, getting the standardized test scores back and seeing the results of months and months of hard work imparting knowledge on my part and absorbing it on their parts—that is another benefit of being a teacher.

Explaining a math concept for the second or third time, focusing more on the importance of my students’ understanding than my own annoyance at their lack of it, considering that it is perhaps even my fault and that I need to figure out a better way to teach that concept—all of these are traits of selfless teachers.

Muddy shoes, dirty fingernails, spilled lunches, torn textbook pages, bad breath, and body smells. These are all part of our world.

Meeting potentially annoying circumstances with a smile and approaching these challenges as learning opportunities—these also are parts of being a teacher.

To be able to smile, keeping in our vision the long-term effects of our efforts, or offering a quick prayer asking God to help us focus on what’s best for our students rather than what is easiest and most comfortable for ourselves—these are also aspects of being a selfless teacher.

These are all commodities that I call “teacher talents.” I believe that teachers have nine or ten talents and that we should use them to edify the body of Christ—not hide them in the ground—even if we do have to clean up vomit, grade stacks of papers, and not make lots of money. Being a selfless teacher is a gift from God, practiced and developed by those who care—those who know how important and exciting it can be to enjoy some of these memorable moments and to reap the rewards of our seemingly unending tasks.

And experiencing these moments is more important than money, recognition, our own comfort, prestige, or success. The children we teach are infinitely and eternally significant to God. They are our legacy, and we get to love and serve them!

Your Classroom: A Spiritual Battlefield

“If only we didn’t have to fight for souls!” This was the lamentation of a teacher friend of mine a number of years ago after a conversation on the difficulties we were facing with some of our students. It summed up our discussion quite well. As Christian school teachers, we are indeed engaged in a battle for the souls of our students, and at times the warfare becomes intense.

But, friends, we are not alone or unequipped in this battle! We have allies, we have weapons, and we have a champion Leader.

I believe one of the most insidious tools of the devil is to make you believe that you are all alone, and that it is up to you to figure things out on your own. He wants you to think that when a challenging need arises in your classroom, it is up to you to be the savior, the knight in shining armor who slays the dragon. And then when you find yourself unable to win the battle, he is more than ready to storm you with feelings of guilt and inadequacy.

It is not all up to you. If you are part of a good Christian school community, you are blessed with many allies, and the most important ones are the parents of your students. I can think of times over the years when I could have solved problems more quickly and easily if I had been proactive in enlisting the help of my parent allies. Raising children to be committed disciples of Christ is an astronomical task, and by sending their children to your school, parents are acknowledging that they need help with this job. Partnering effectively with parents in the battle for children’s souls is powerful, and I believe it is a beautiful example of the way Christian community is intended to work.

Besides parents, you probably have a principal, board members, and co-teachers as your allies. Make use of them. I am grateful for fellow staff members who give advice and encouragement, or sometimes even just commiseration. I felt the absence of this keenly when I was the only teacher in a small school, and so I sympathize with you if that is your situation. Perhaps you can find ways to connect with teachers from other schools. Teacher friends are wonderful allies.

In this battle for the souls of our children, we are also wonderfully equipped with the armor and weapons described in Ephesians 6, and we have a champion Leader to guide us. We have God’s Word, His Spirit, and the powerful weapon of prayer. How often do you pray for each of your students by name? When challenges arise in your classroom, do you naturally turn to prayer first, or is it a last resort? As we follow Jesus and are continually formed more and more into His image, we grow in our ability to fight spiritual battles well.

Never give up hope for any of your students, even when it seems that nothing is making any difference. The Holy Spirit is at work in their lives, even when we don’t see it, and we need to trust that work. One of my former students is currently serving a prison sentence for crimes he committed, but I believe that God still has great plans for him and that this is not the end of his story.

Also, I recently experienced the joy of seeing some of my former students make a public commitment to Jesus through baptism, and I listened to their testimonies. It so happens that several of them were the main characters in the discussion that I referenced in the beginning of this post. Fighting for souls is never easy, but we can battle courageously as we keep our eyes on Jesus and let our hearts be filled with hope.

Spring Fever

Bright sunshine, balmy breezes, stuffy classroom, worn workbooks, antsy students, dreamy teacher—it’s springtime and the end of school is beckoning. The countdown is getting lower but there are still some weeks left until the welcome summer break. Do we just set the autopilot and coast till the end of the school year—maybe trying to just hang on and not let everything fall apart? Or can we put these last weeks to good use and finish well?

I think all of us (except for a few first graders who still think school is their favorite place to be) are becoming weary of school life and school routine. We could all use a boost in school fervor about now. For the teacher it can become easy to let things slide. We are almost finished, so does this class time or subject really matter? Students also can become lax in their diligence. They’ve done well enough all year. Things they’re learning now will be reviewed next year. Is the rest of the year really important?

I would like to suggest to the teacher that you take thought for next year. Bad habits that develop at the end of this year will need to be broken at the beginning of the next. Take stock of your classroom management. Is it still going strong? Are you still following through? It is easy to let things slip at this time of year. But it only leads to frustration for both the students and the teacher. I recently found that it was time to introduce the next level of my discipline plan. It hadn’t been necessary up to this point but now I needed to call students to a new level of excellence. Don’t be afraid to implement a new strategy if that is what it will take to help students and teachers finish well.

Are the lessons becoming humdrum and lacking in student engagement? Often by this time most of the difficult subject material has been covered and students are working with review materials more independently. The lesson counts may also be winding down and students have more free time. Take advantage of the easier load to add in a few extra projects that push for excellency and add some spice to the normal workbook pages. A few ideas to spark your own:

- Have students write and illustrate their own story books as a language arts supplement.

- Write and “publish” a classroom or school newspaper about the events of the year.

- Have students create a poster, shadow box, three-dimensional project, etc. for a science or history addition.

- Have students research and prepare a speech for a topic of their choice. Additional sparks of interest could include posters on their topic, food samples, or costume that supplement their topic.

- Take math to the field. Measure the size of an acre. Using the parents’ jobs as starting points figure out some real-life math scenarios. Plan a store for students to buy (and sell) items for coins and paper money. Have students prepare and serve a meal for the class.

- Take a field trip to a local lake, pond, or river and explore the biology found there.

- Grow tadpoles into frogs.

- Visit a birding area or just the woods in the back of the school and look for spring migratory birds.

- Be practical. Not every idea will fit every grade level. Use this time as an opportunity to take the abstract workbook lesson and turn it into real-life usage.

Those warm, sunny days call us outside. Vigorous exercise while playing aids the classroom work. Exercise is good for our physical, mental, and emotional health. It can be tempting to spend extra time at recess. Occasionally this is good. Just remember that making it an everyday habit does no one any favors. But make sure everyone gets the chance to enjoy being outdoors. Take time to clean the playground of trash, dead leaves, and sticks. It might be even better to figure out how to effectively take the classroom outside at times. Soak up some sunshine while eating lunch. Send students out to write a paragraph about what is going on around them. Delight in the warmth and renewal of spring.

Teachers set the tone for their classroom. And yes, teachers, sometimes you are weary to your very bones. Maybe you have a student who takes extra diligence and maintenance every day. Maybe you have questions about a student’s ability to move on to the next grade. Maybe your duties seem overwhelming. Ask God for grace and wisdom and strength to continue to finish well. He gives it out liberally to those who ask (James 1:5).

The last weeks of school should not be viewed as a cell where we are just counting down the moments until freedom. You will never have these days again. Use them well!