All Content

A Suffering History: Conflict and Sacrifice for the Cause of Christian Education - Part I

Priorities for the Youngest Students

What should kindergarten and first grade teachers prioritize in order for their students to have a positive early school experience that equips and prepares them for the rest of their school years?

1. Security. First of all, students should feel that they are in a safe environment where they feel cared for and protected. Five or six is still a fairly young and tender age, especially since most of our students are used to being at home with their parents for almost all of their preschool years. It’s best if they can visit the school while it is in session. This is best done with a parent holding their hand if necessary, leading and guiding them, encouraging them and reassuring them that this is a safe and enjoyable place to be. They should be welcomed by the teacher and other students, who should smile and be friendly.

The environment makes a huge difference as well. It should be warm, interesting, and inviting, opposed to cold and sterile. We usually have age-appropriate books and a few puzzles out on tables. Art adorns the walls, and our current art projects are usually in progress laying nearby. There should be an extra desk for any visiting student to try out, and a carpeted, comfy reading area. Ours has a teepee on a soft rug, crocheted fruits and vegetables, books, and brain games in it. Students are encouraged to explore these areas at some point in their visit.

We have had students enjoy their visits the most when they were included and got to participate in whatever classes were going on when they arrived. We have extra papers or supplies nearby, and students are invited to join in the current classes, but they are never put on the spot and asked to answer a question unless they want to.

One of the greatest fears younger students have at school are the older students. It helps if they are introduced to these older students while they are seated, not standing up and looking tall and scary to the younger ones. I ask my older students to smile and say hello. We strive for more of a family atmosphere, and being kind to the youngest students goes a long way toward this goal.

All of these should help students to feel welcome, safe, secure, and cared for at school. If students are worried or don’t feel safe, they are going to have a hard time relaxing or learning.

2. Calmness. The early years of school set a precedent and mold a student’s state of mind and how they approach school. School should usually be quiet, calm, and orderly. Nothing should be rushed. Everything should be purposeful and calm. The teacher should set the pace for this by leading her students well and setting a calm example. Softness and gentleness should be the norm, and she should lead out with authority and calmness. This does include lunchtimes and breaks. There should be times of laughter and rest—a mental break—but not a time of chaos and disorder. After lunch, it is more effective if students have a bit of free time, but not so much that they get into a rollicking game of softball. If you've got a history class after that, they are probably going to have trouble paying attention. I have found that it works better if students have just enough time to relax a bit. Then their minds will be refreshed and ready to get back to work. P.E. class is a little bit later in our day, with classes like music and art which don't take as much focused energy following it.

3. Order. Working side-by-side with calmness is order. There should be a set schedule for the day that is usually pretty closely followed so that students, especially the younger ones, will know what to expect. There is also safety and comfort in following a daily “rhythm.”

The teacher should also make sure that the students are all listening when directions are given, and that students understand exactly what it is they are to do. Practicing doing things correctly ahead of time (raising hands to speak, etc.) is very helpful for all students, but especially the youngest ones.

4. Handwriting! From the very beginning, having good handwriting should be stressed. Students should learn the correct way to hold their pencils, using the thumb and first two fingers in a “lobster pinch.” The triangular rubber pencil grips are extremely helpful in this endeavor, and we make sure that all students start out with them and have access to them as long as they desire.

Students should also learn how to correctly make the strokes the right way. Teachers should repeatedly model this in large, bold strokes on the board, and then have students practice this with them in the air, finally repeating the process on paper. The larger lined paper should be used. I prefer the kind that only has one dotted line down the middle and a red line for the baseline. Students should also clearly understand which letters go “down to the basement:” g, j, p, q, and y. Students will often try to keep the letters above the line if they are not taught properly.

They should also learn to press down fairly hard with their pencils and make bold downstrokes—not faint upstrokes—when writing. This will result in purposeful and precise strokes, and not wispy light ones.

5. Focused work ethic. Having an overall classroom culture of focusing on work when it is time to work, but then having order and calm when it is time for the less-focused activities is a wonderful balance. Students will feel safe in these parameters, know what is expected of them, and will perform accordingly.

6. Consequences. While obviously these should not be stringent, there should be set classroom procedures that allow a teacher to maintain both his classroom culture and calm demeanor. That’s where consequences come in. This often entails a warning, followed by a time out in a space away from the rest of the class but still visible to the teacher, and finally, a written slip or communication with a parent. Students thrive when they are operating within set parameters with known consequences if they make the choice to function outside of these guidelines.

Wonder through Science

Our interest here is thinking, how can in science class, can we help to maybe loosen the scales that are on our eyes and really see, really see the presence of God, the wonder of God in the world that he's made. So how can we teach science? How can we explore the created world that keeps that wonder, keeps that sense of awe, that sense that I'm small and this world is amazing that God is made. So, I asked the question, how can we, in our classes, take off our shoes? How can we cultivate this ability to see to where our jaws drop? And we say, "Wow. Yes. This is amazing!" And I'm going to suggest that, while the best jaw dropping is done in the context of seeing God behind it all, just dropping the jaw is in the right direction.

So here are eight ways to take off our shoes.

One: Look until Breathless

Let's look and keep looking until I am breathless. So, this first one is about what we do as teachers. And I'm suggesting if we're going to inspire wonder, we have to feel wonder. And that means we're going to have to prepare. We're going to have to look. We're going to have to dig into our subject matter to the point where we come alive to it. If you want them to come alive to the wonder of the creative world, you have to really be alive to it.

Marlene Lefever said this, "Becoming an effective teacher is simple. You just prepare and prepare until drops of blood appear on your forehead." You see, it's that kind of work that we need to do. You might say, "Oh, that's going to kill me if I do that." No. No. No. You have to push through the complexity before the simplicity comes. You have to push through some of the work before you really the scales drop off your eyes and you say, "Woah, this really is amazing!"

We should not expect to inspire wonder if we don't thrill ourselves to what we’re teaching and learning together. Second, we need to identify a wonderful, a full of wonder, a wonder full focus or demonstration that can be do, that we can use. So here we're going to be talking about demonstrations. Some demonstrations have wonder built into them.

I taught electricity and magnetism for many years. I've used Van de Graaff generators, which they can be, wonderful. I've made use of Tesla coils. I've used a variety of things, made little, small generators, or had the students make motors, a variety of things. But you know, I still, after years of doing that, the old (which I know many of you have seen this), but the old magnet in two is just a wonderful way of talking about electricity and magnetism. And in fact, it’s part of the reason what makes it so wonderful is that it's counterintuitive. Everybody knows that cardboard, there's no attraction between a magnet and cardboard.

And now, this on the other hand is a what kind of tube? Looks like copper. It's a copper tube. Is a magnet attracted to copper? No. It is not. No attraction there. And we all know that when objects drop, they drop at 9.81 meters per second squared. That's the rate of acceleration. And if we drop that through this tube, it drops at that rate, 9.81 meters per second squared. And so, when we drop it through this, which is no different than the cardboard tube in terms of neither, subtracted to neither. When we drop it through this, it should also drop through at nine point eight one meters per second squared. But this time, I have plenty of time to catch it. See, that's a wonderful demonstration. And then we can go and talk about all kinds of things related to electricity and magnetism and so on.

Two: Modify Ordinary Demonstrations

And, you know, there there's lots of demonstrations that you can do. Just take common ordinary demonstrations, and by changing them up, adding features or whatever, you could turn them into something wonderful. Every child has grown up pouring vinegar into baking soda. I mean, that's just that's a right of growth or something for us. And so, you, but you can take that, and if you just did that, it would be, oh, what's the big deal? If you put it in a test tube, put a cork on it, and the cork spout it out, that would add some wonder to it.

But you could also do things like... Let's just take a candle. So, what we're going to do is mix up some, you know, after we're talking after we've talked about the gas, carbon dioxide that's produced when we have baking soda and vinegar, we'll just mix them up into a container. Then we'll talk about how carbon dioxide is heavier than air and that it's a fluid, and you can pour it. And so, in order to demonstrate that we can pour it, we'll create some carbon dioxide, and then we will see if we can pour it down the trough and put out the candle. Since flames need oxygen, carbon dioxide covers it. So, I'd prefer to use a, a container like a I generally use a big gallon jar, but I didn't have one this time. So, I'm just doing it in a bucket. The bad thing about this is you can't see, the fizziness and everything. But it's producing some carbon dioxide in there. And now we will try to pour it down the trough, and boom. It's gone. Thank you.

So again, you can just take some ordinary that they're used to and add some pieces to it to increase the wonder value.

Three: Surprise after Content

Third, content first, then the surprise. Once you have a reputation of giving discrepant events or wonderful dim full of wonder demonstrations, then you actually have some capital in the bank that you can spend by teaching content.

So, if this is sitting there in front of your class, again, you can teach for an hour, and they're going to still be watching because they wonder, when are we going to get to the gun? And, but so what you do is you take, you know, your kind of maybe motion toward that a little bit, "What we're going to do today is we're going to talk about..." Maybe it's single displacement, double displacement reactions. Maybe you're just talking about balancing equations. But you can talk about, say, "Today we want to look and consider this equation and, see what's going on." We might label all of the different components. We might come along and say, well, "Is this a solid, liquid, or gas?" And so on. And so, we get in other words, we're just talking about a lot of things, maybe reinforcing, reviewing, or maybe I would take an equation like that and use it to teach a whole bunch of stuff, kind of build it around the one equation. We'll explore different parts of that. And so, calcium carbon, oh, we have some of that here. It's a rock-like chemical. And so, what are we doing? We're just putting it with water, and that's producing calcium hydroxide to form a lime. Of course, it's a base that we're producing. And then what is this thing? Has anyone ever seen it? Well, eventually, you can tell them that's acetylene, and someone will start to say, oh, we have that in tanks at our shop, and it burns. And it's okay. Well, let's see. Let's go ahead and take that gas that's produced, and this is a gas. So, acetylene we're going to take acetylene, and we're going to add oxygen to it. And what is that going to produce? It's going to produce carbon dioxide plus water, but also in the process there is heat. And we also know that, if we add a match and a fire to that, there's the potential for an explosion. So that's what this is for. So, you see the idea though is to be content rich. Talk about a lot of things, teach a lot of things, all hinting that something's coming.

And what's the something? Well, we need some water. I have some water here. What we're going to do is put the water into the well. So that's going down here in this portion. And then we're going to get some of our calcium carbide. I don't want to introduce it to water too quickly. And so, we put some calcium carbide here in the... This is just a piece of PVC. Stick it in here. Now, when I turn that, that's going to dump the calcium carbide into the water. And that first equation will be descriptive of what happens, and it will be producing acetylene. So, I'm going to put... You'll notice this this cap has a little hole in it. That's where we can introduce the fire. And then, I'm going to... You may want to hold your ears when I put the fire here. It can be loud at times. So, if you're also a music teacher, you may want to hold your ears. Okay. So, we will, at this point, go ahead and turn that. Turn it a couple times and get it in. Hopefully, it's making some acetylene there for us. And then we'll see where it's pointed to. [loud noise] And there we go. There was the second equation.

Now, if we wanted a little bit more excitement at this point, somebody would say, "Hey! Could we put some ammunition in this thing?"

"Oh, we could try it again with that."

There is enough explosive potential that you want to be sure whatever you put in here can get out or else other things will blow up and it won't be fine. So, the way it is, I generally just do not put something in just to make sure that it is reasonably safe in an indoor type of setting. Okay. So that was, content first.

Four: Mystery, Discover, and Wonder

Then the surprise number four. Surround your presentation with the language of mystery, discovery, and wonder. Part of being a science teacher is choosing language that that actually cultivates wonder. Back when I taught chemistry, with time I began to realize that the story of how we figured out that there are atoms and then something of what is in an atom, the protons, electrons, and neutrons, that that is a mystery story. And I started teaching it that way, and started thinking of it as a black box, and so on. And after a year or two of kind of playing around with that concept, probably the best compliment I ever got and as a teacher is when someone just came up and they said, you know, "This this is so fascinating. What we're learning about chemistry and the atom and so on. It's just like a great mystery story." And I hadn't said that that's what I was trying to do, but for them to feel that and recognize that was great.

So, let's say that you are maybe you're working with titration, or, again, maybe a double displacement reaction or it's just kind of a hybrid. But, talking about this one and so we have an acid plus a base produce, in this case, sodium chloride and water. And you could do so the traditional way is to say, "It's an acid plus a base produces salt and water." And that's accurate. That's good. But see, you can also surround that with a bit more mystery, a bit more excitement if you've talked about how hydrochloric acid is the stuff that's used to clean bricks off. And if you ingest hydrochloric acid, you will cease to exist as a normal human being. And I mean, hydrochloric acid is nasty stuff. And then we talked about sodium hydroxide, and I could talk about the person that I knew that had swallowed some of that and how it ate through their esophagus before I mean, they were they survived it, but they had to put in an artificial... So, what we have here is a killer plus a killer produces believe it or not. What? Table salt! Salt water! I mean, you technically could technically you could do this equation in exactly the right proportions and drink the result, and it would be fine. See, that kind of interpretation of what we're doing helps to cultivate a sense of, of the significance of what is going on.

When you can, when it is justified, make outlandish statements. Now be careful here. I've made some outlandish statements that I have had to retract because they weren't correct. And so, you want to be sure. But here's one that almost always will get high school students going, and that is, you say, you know, I have a toy gun or something. But you say, "If I have this bullet and I drop this bullet, it will take x amount of time to get from here to the ground. Now if at the same time I drop that bullet, I fire this gun. Or at the same time that the bullet leaves the end of the gun, I drop this bullet, and they're both at the same height, they will hit the ground at the same time." See, now that's an outlandish statement. That is not intuitive, and very few people... They’ll say, "I'm telling my dad."

But there's when we find those things, and they're often there in science class, we can use those to kind of get the get the wonder bubbling.

Five: Combine Demonstrations

Fifth, we combine. Combine our demonstrations. Combine our studies with story. Include story. And these don't have to be elaborate necessarily. So, this particular... This is just a piece of glass that's been made into a mirror, but there's nothing special about it really. It’s slightly concave to keep this disc toward the center of it. This is just a piece of metal.

Here's the story. Quite a few years ago, there was an engineer out in California, and he did not have quite enough work to do. So, he was sitting at his desk sometimes just kind of existing. And one day he got a quarter out and he was spinning it. Quarter was spinning there on his desk. And then he started to say, "I wonder how another, a heavier coin would spin."

Then began to realize that when you spin something like this, it's actually not just spinning. It's rolling and spinning. And so, we begin to say, "Oh, well, that's actually scrolling." And that is a term. It's scrolling. It's not rolling or spinning. It's scrolling. And he got on the search for how, "I'd really like to find the optimal scroll." The way that the scrolling can happen that would maybe go the longest. And so, he tried different metals, different angles on his disc, different weights, different surfaces, and he found that this particular weight, size, and metal composition with a certain machining at the corner is one of the best. And so, we will scroll. You'll notice I didn't even really try to really spin it hard. [prolonged spinning] At this point, you would expect it to have been stopped. [ more spinning] So simple little novelty combined with story maybe can inspire things like, "Oh, what studies could I do? What could I experiment with?"

Here's another one. This is a Tantalus cup. Also sometimes known as a temperance cup. Let's say, you can see it looks kind of like a wine chalice, perhaps. And if you look at it, you'll see there's some, it looks like the Parthenon, pictured on it some Greek imagery and so on. The Greeks, some say it was Pythagoras that developed this cup. And he did it in order to encourage temperance in your wine drinking. And so, the way this works is that for the person who was temperate in their wine drinking, say, you know, had a modest amount of wine, they could pour that into their cup, drink it, and everything was great. On the other hand, the person who was in temperate and they had a lot of wine in their cup, it would all drain out. I see all a little bit left there perhaps. Okay. So, you see, I couched that demonstration in just a little bit of a story about the Greeks and wine tasting and so on. But at this point, what I would actually, I might say, "Okay. Your test today is to draw what that cup looks like on the inside." And then we use that after we have discussed, air pressure. We've talked about siphons. We've talked about, yeah, basically in that arena. Use that as a test.

Six: End with "Why?"

Six. Sometimes ends with "Why?" See, teachers I have found, at least I know this is true about myself, is that when I have a good demonstration, I want to explain. And probably a big shift in my teaching over the last thirty years is to move from quick explanations to having the class explain what's going on.

So, for example, if we have just been and we've been talking about density, I'll use this density bottle, and we observe that there's some kind of fluid, and there's white beads and blue beads, and then all we get there is shake it up and observe. [observing] Why? Describe it. I don't have to explain it if we have been talking about densities and so on and how that works. Again, I may just say, " Okay. I'm asking you now in the next five minutes to write a paragraph explaining why."

Or maybe we're doing a unit on light and index of refraction. And then I bring this to the class [and] ask, "What do you see?" It's canola oil. But in addition to that, There's another beaker in there. Why does it disappear?

Seven: Go Big. Get Dangerous.

Number seven. Go big. Get dangerous.

Another one of my favorite quotes is that "a good demonstration is one with the possibility that the teacher may die." That has a way of increasing wonder.

So, for a long time, I did a little something with a ping pong ball and used a straw to blow past it and show that when you have high velocity in a liquid or a gas, that there's actually a lower pressure there. High velocity, low pressure. Low velocity in a fluid is higher pressure. And so, I might blow from a straw over a ping pong ball, and you'll see the ping pong ball rise to meet the air.

Or go over to a faucet, you have water flowing. It's high velocity, but it's low pressure. So, if you take a ping pong ball on a string and bring it over close, the ping pong ball will be drawn over to the water. You can do it that way. Or you can go bigger.

You can use this for your high velocity generator. And fortunately, it produces a ball for us, so we will see what we can do here. [leaf blower noise] Instead of blowing it away, it actually keeps the ball there. And we can move it a little bit because out here it's high pressure, and it's just pushing it into the low-pressure area, keeping it clear. Can you go higher with it? [leaf blower noise] Of course, we can go to the point where it won't stay in.

You've probably taken, say, soda cans, put a little water in them and then heated them up so that things would expand inside, turn them upside down in water, they implode. Well, that's great.

But then you think, "Oh, you know what? We could go big. We could get a gallon metal paint can and do the same thing with that."

But you can say, "Oh, we could go big." And then you get a fifty-five-gallon drum and do that. So just be thinking bigger,

Have you seen those air blaster? Forget what they're called exactly, where you can do smoke rings with them and so on. Those are great. But you can also get a big trash and create a mammoth one that will produce these humongous smoke rings.

Go big. That has a way of increasing wonder, not just for high school students, but for teachers as well.

I was at the garden sale here a couple years ago and found this. It's a martini glass, if you know it. A big one. You know, what a great way to do, color change demonstrations. So, in this case, I have potassium iodide solution in there, reasonably clear. In the cup, I have lead nitrate. So, this will be double displacement. We're going to produce potassium iodide. The potassium's going to mix with the nitrate, potassium nitrate, and we're going to have lead iodide. Lead iodide is coal.

So, let's mix this together and see what we got. Now you could do that in a little beaker or something, and that's really cool, but there's something would you agree? It's a little bit more wonderful by having it larger, bigger, and so on.

Eight: Point to God in Authentic Ways

Finally, point to God in authentic, fresh, unique, creative ways.

Now, I want to say again that the students having an experience is saying, "Wow. That's pretty neat. That's amazing! That's incredible! Wonder how that works? You know, that's really interesting!"

That is in the right direction. You don't it doesn't always have to be directly connected to God. A posture of wonder is a very Christ like posture. It's a humble posture. It's the kind of posture that we need to be seeking to cultivate. But I find that there are ways in which, in those moments, you can point to God that's not tacky and it's not cliched, and it caps things off.

So, I offered some questions. And where you get them thinking about, you know, what all is behind. So, ask good questions. Sometimes quotes can help you here. I'm going to give an example in just a moment. But there are some scriptures. But be careful here, folks, because we have this tendency to just tack a scripture on to something that really does not connect with hardly anybody. I remember seeing an I remember seeing an egg separator you buy at a Christian bookstore, remember seeing an egg separator you buy at a Christian bookstore, and it was, yeah, it was a real egg opener, you know, to kind of put the egg in, you put the thing down and puts in a whole bunch of pieces. And then she had a bible verse on it. Nothing can separate us from the love of God. Okay. Let's avoid that. But say, like, the passage there in Deuteronomy 6, the Shema, "The Lord is one." I have found that passage to be so helpful in actually making connections. "The Lord is one."

The heavens declare the glory of God. Psalm 19 And we could go on. And then, you know, I find that that songwriters often get this right. So, we've already mentioned, "This is My Father's World." "I Sing the Mighty Power of God." Some of the songwriters really have brought together the creative world and the creator in ways that I think we can use sometimes in our classes that might feel fresh. But above all, I would just say, to stay tuned to your students. What are the ways that authentically connect them to God? That that don't feel tacky to them, that feel genuine. And you're going to have to learn it. You might even have to change. I have to use a different language now than I did twenty-five years ago in order to do some of those things. We can look for ways to even sometimes obliquely turn the attention of our students toward not just the wonderful thing that we've done, but a recognition of the one who's behind it.

If I were to do this in a classroom setting, I would lead a discussion on what are the five most important numbers in mathematics. And those numbers are zero, one, π, e, and i. And these numbers are the numbers that you could say are behind the major mathematical disciplines. [I] won't get into that, but I would talk about each one and how each one is absolutely phenomenal. It's an incredible number. And how numbers like π, you know, 3.1415927 ad infinitum forever number, amen, non repeating, non terminating. And then e, a similar kind of number, and I talked about, and and I can't. I want to. I wanna talk about e because e is so amazing. All of these numbers are amazing. And then after we talk about those four, then we talk about how i is even in kind of in a different league. It's in a different world. And and so we have these really strange numbers, and yet we can put all five of them together like this: e raised. We're using not multiplication, division. We're using we're using powers here.

e^πi+1=0Now, I need to build that up in order for us to feel the wonder of that. But that's amazing. And then you see, after we'd explored kind of some of that, then I would end with this quote. And this is a quote from an MIT professor, an atheist. He said, "There is no God, but if there were, this formula would be proof of his existence." That's an oblique way, and I think compelling way, a non cliched way to point our students to the God behind, not just science in the creative world, but mathematics as well

A Hole Is to Dig. A Test Is to...Give?

Several years ago, I visited a used book sale in its final hours before closing. The deal was hard to beat - fill a box for just a few dollars. My children added many books to the stack, and we were soon headed home with a hefty collection of ‘new’ books. Because the selection had already been picked through for several days by savvy bookworms, I did not plan on finding much of value. To my surprise, I stumbled upon a little gem of a book that has become one of my favorites—not for its pictures or its rich vocabulary but for its startlingly realistic glimpse into the thought-world of a young child.

The book is called A Hole Is to Dig: A First Book of First Definitions by Ruth Krauss (1952). I would describe it as one of those books for children whose secondary purpose is to entertain adults. The book begins with a small note of thanks to the students of several nursery schools and kindergartens, presumably for their contributions and inspiration for writing the book. Patterned after its title, the book includes page after page of simplistic ‘definitions’ that are not altogether intuitive to the more mature mind (Krauss, 1952):

- “Mashed potatoes are to give everyone enough” (p. 1).

- “Dogs are to kiss people” (p. 5).

- “A lap is so you don’t get crumbs on the floor” (p. 26)

- And my personal favorite: “A floor is so you don’t fall in the hole your house is in” (p. 38).

As fun as it is to browse through the book and to chuckle at the undeveloped perspectives, it may be equally unsettling to realize that we as ‘grown-ups’ are not always so sophisticated in our thinking either. Seeing through a glass, darkly, tends to be our default. We can become so accustomed to seeing the world (i.e. our classrooms) through a foggy lens that it can be difficult to identify when we have slipped into thinking patterns like those displayed above. Consider the following statements:

- A test is to give so that the gradebook is filled.

- Student desks are to rearrange every nine weeks.

- A bulletin board is to stress out the teacher about how to best display his (absence of) artistic talent.

Like the quotes above from Krauss’s book, these statements demonstrate a lack of clear purpose; something about the ends and the means do not fully align. For example, most hosts in their meal planning have a desire to ensure all the guests will be adequately served. This objective is not accomplished by adding mashed potatoes to the menu but rather by strategically planning out serving sizes and purchasing sufficient ingredients. The mashed potatoes are merely an efficient tool for accomplishing the task. I may be embarrassed as the host if some of my company goes without eating because I thought whipping up some mashed potatoes would be adequate for the need. In another example, it may be nice to look at the floor during a meal to see how effectively everyone’s laps have protected it from becoming covered with crumbs, but taking a long-range view makes one wonder what it will look like once everyone stands up. There are likely better ways to keep the floor clean, but as long as we maintain that laps are the answer, we will likely not brainstorm to identify a better solution.

For teachers, the question is this: are there routines in our school day that we take for granted? If so, what are they? How could these tasks or routines be improved? By identifying these areas, we open up exciting opportunities to innovate, improve our teaching, and create a classroom that runs more smoothly.

In the earliest years of my teaching, I distinctly remember the large bulletin board in the front of my classroom. When I looked at the expansive blank surface, I saw a clean canvas on which to create a veritable work of art. I went about setting up the rest of the classroom to my specifications, and all the while, I thought about what masterpiece I would create that would stun my students, my fellow staff members, and all the guests who would pass by my room. Needless to say, this extraordinary amount of pressure made me start and restart dozens of times. How would it be decorated? What cute, snappy pun would fit the theme? In the end, my board earned a few compliments, added a little to the room’s atmosphere, but contributed absolutely nothing to the students’ learning.

I will never forget the day I stumbled upon the idea of functional bulletin boards—displays that were not purely decorative but that contributed to the learning environment. An effective use of bulletin boards is to display student work without adding many extra ‘frills’—let the students’ work communicate their learning without distraction. Other bulletin boards are informative or interactive and are meant to display reference material that will benefit students. In creating my present bulletin board, I have invested in some nicely themed fabric as a backdrop (bye-bye unwieldy bulletin board paper), some sturdy burlap for the frame, and reserved the space expressly for reference material my students will need on a regular basis. Perhaps the best part of all is that I can reuse it year after year, if I wish. No, it will not end up in the Met or the Louvre, but it has saved me immense amounts of time—and it is something that my students and I actually use. A bulletin board is not meant to be an added stressor.

Consider the other classroom items or practices mentioned above: tests, student desks, grading, etc. Now ask yourself this: what are they for? Be prepared for an answer that may be different from how it is currently being used. Regarding tests, we often default to giving tests because ‘It’s time to give a test!’ or ‘I better get at least one more test grade before the end of the quarter’. There may be times when these statements are valid, but perhaps the better thought would be ‘We are at a point in the study when it would be helpful to measure how much students have learned.’ For student desks, I like to move these as needed and prefer not to restrict myself to a certain time frame. Scheduling a desk change can be helpful, but students quickly come to expect (i.e. demand) it after just a few times.

I have once heard it said that the spring of the school year is the best time to experiment with our teaching to see how routines and structure may be improved. By this time, our students are hopefully operating well in the current systems and will likely enjoy the opportunity to try something new. As a middle grades teacher, I am usually up front about this with my class, and I generally tell them that I would like to try an experiment to see how well we can make something work. They are usually more than happy to oblige!

As we think about the routines and tasks in our classrooms, where are the opportunities for some rethinking (Grant, 2021)?

References

Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don't know. Viking.

Krauss, R. (1952). A hole is to dig: A first book of first definitions. Harper & Row, Publishers.

Image by Freepik.

Tips for Improving Classroom Engagement

I will confess to you that I find it difficult to pay attention to a sermon or lecture. As a primarily visual learner, I would much rather read a book than listen to a podcast. I have had to learn ways to compensate for my lack of listening skills, and I know that I need to take deliberate steps (such as taking notes) to keep my mind from wandering. If I as an educated adult find it difficult to sit and listen for long stretches of time, how much more difficult must it be for our young students? How can we keep their minds engaged in learning? Here are a few simple tips that I have found useful in my classroom.

Keep them moving. This is especially important for lower elementary students. Children have boundless energy, and it works best if we learn to put that energy to good use rather than trying to suppress it. Generally, I do not keep my students sitting for more than fifteen or twenty minutes at a time. We get up and do stretches or exercises between classes. We stand and recite poetry or Bible memory with vigorous motions. In history class, we get up and act out parts of the story I have just read. Sometimes when we need a break (especially if beautiful weather outside is calling), we go out and run a lap around the school building.

Have everyone participate with fingers. This is a very simple tool that quickly elevates participation and engagement and can be used in many ways. For instance, when we are reviewing nouns, I might have sentences on the board and say, “Count all the nouns in sentence one. When you are ready, put your fists up. When I say ‘Go,’ show me with your fingers the number of nouns you counted.” For a review of important people we studied in a unit in history, I write the people’s names on the board along with a number. Then I read various facts about them. Students show me with their fingers which person the fact matches with.

Have everyone write. Instead of the classic “teacher asks a question and the smart, confident kids are the only ones who answer,” have everyone write an answer. My students all have small whiteboards and markers in their desks that we use for this, but scrap paper works as well. This can be used for various subjects, but the basic idea is to have everyone interact with a question by writing an answer. Sometimes I ask everyone to hold up their boards to show me what they have written. Sometimes I call on one or two students to tell their answers to the class. This can be a good way to get shy, hesitant students to share their ideas and answers. I can say to that type of student, “I see you have a good answer written down. Please read it to the class.”

Encourage peer teaching. Students are sometimes astonishingly good at being each other’s teachers. Doing paired activities is a great way to get everyone involved and to have students learn from each other. I especially like to do this in math class. When working practice problems, I have students do problems on their own and then compare answers with the person beside them. If the answers do not match, they need to work together to find mistakes.

Incorporate humor. Our classrooms ought to be places of joy where laughter is frequent. Break up a tedious lesson by telling a joke. Laugh at your own mistakes. Sometimes it is just fine to put work aside and be silly for a little while.

It is impossible to have all our students paying perfect attention one hundred percent of the time. Yet it should be our goal to increase that percentage and to keep our students engaged in learning.

“Come to the Kingdom for Such a Time as This” (Esther 4:14)

Is teaching a calling or a profession? Esther's bravery in the face of adversity serves as a model for educators, emphasizing the importance of recognizing teaching as a calling rather than just a profession. Using stories Robert Bowman highlights the significance of humility, courage, and perseverance in fulfilling one's role in education. Ultimately, the message encourages educators to view their work as part of a divine calling and to trust in the impact they can have on the lives of their students, echoing Esther's timeless question: "Who knows? But you have been called to the kingdom for such a time as this."

Savants—The Extraordinary

How can we learn to recognize and nurture the unique abilities of every student?Kervin Martin explores the exceptional abilities of savants, individuals with disabilities who excel in areas such as mathematics, music, and art. Examples include those who have overcome challenges like blindness, autism, and brain damage to showcase remarkable memory and cognitive skills. The stories of individuals like Orlando Serrell, Jason Paget, and Derek Amato highlight the potential that all humans possess but may have lost over time.

Healthy Boundaries—Rewarding Relationships

Boundaries are essential to healthy relationships, but how should we go about establishing them? What qualities are necessary for rewarding relationships?Jonathan calls us to humility, open communication, trust, and transparency as we exemplify Christ-like behavior in our relationships.

A Vessel Unto Honor

The master teacher seeks vessels of honor for his kingdom. In light of that, what character qualities should teachers embody?Kenneth Kreider emphasizes the importance of humility, discipline, and dedication in teaching, urging us to be vessels of honor in our work, standing on the foundation of truth.

Grading with Rubrics in the English Classroom

When English teachers get together, the topic of grading will come up—often with complaints about the time grading takes and the difficulty of grading essays fairly. While part of that is just the nature of the job, essay grading can be made simpler with the effective use of a well-written rubric.

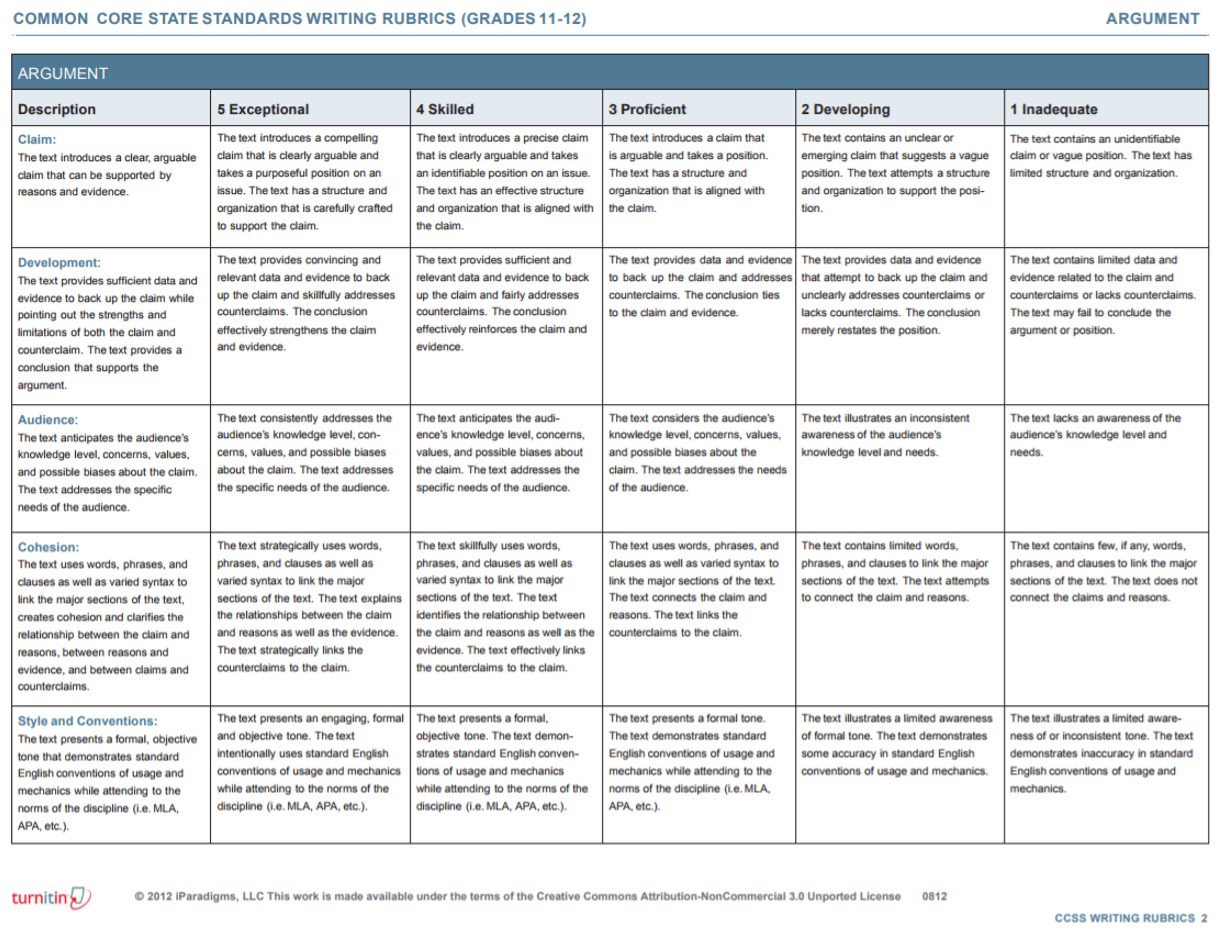

A rubric is a list of characteristics desired in a final assignment, with different points assigned for each level of achievement. An analytical rubric displays in a grid-like formation that matches a description of student achievement to different levels, such as exceptional, good, satisfactory, and poor, or to different numbers of points, such as 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 (see below).

(Note that while this rubric comes from the sometimes-debated Common Core, it provides a good starting place and can be adapted, as described later in this blog post.)

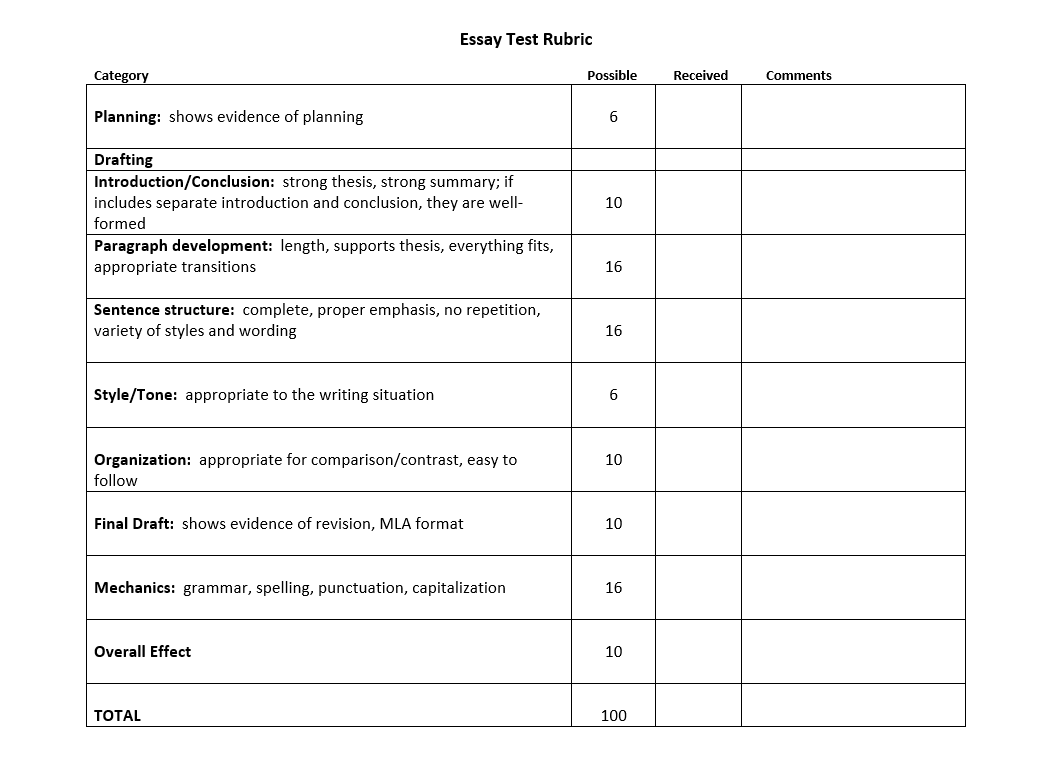

A holistic rubric describes the desired outcome for each characteristic, and the grader attaches a point amount to the characteristic (Fuglei 1).

While some critics argue that rubrics stifle the student’s creativity and limit helpful feedback, most English teachers agree that rubrics allow the most objective grading for essays. Used as a teaching tool during the writing process, the rubric allows the writer to see the needed characteristics before turning a paper in. The teacher can explain each attribute on the rubric as a writing lesson. Then used as an assessment tool, the grader can look specifically for the required specifications when checking the final draft. The key, then, is to create a fair and easily used rubric that still provides feedback for the student. Here are some tips.

- Don’t start from scratch when creating a rubric. Most writing curricula include grading rubrics. If not, they can be purchased or even found for free online or in teaching resource books.

- Modify already existing rubrics to meet your student’s needs. If there is a specific writing characteristic that you are emphasizing, be sure it is included on the rubric. Or if you know your class needs help in a certain area, include it as a goal on the rubric.

- Individually tailor rubrics to students. By leaving points for one category open, each student can set an individual goal (or the teacher can set it) to work on for a specific assignment. I often build upon a previous rubric, using a student’s lowest category to set the individual goal on the next rubric.

- Leave room on the rubric for comments. Rather than just assigning points, tell the student why that amount of points was assigned. While comments can also be written on the paper itself, it often helps to have them all together on one page.

- Keep rubrics as a portfolio of writing progress throughout the year. The student can use each rubric as a guideline for the next paper. At the end of the school year, the cumulative rubrics show the progress made.

- Keep a rubric to a one-page length. Longer rubrics are cumbersome both for the writer and the grader. A shorter rubric provides focus.

- Make the point value for each category equivalent to the importance of the category. If the teacher is focusing on mechanics, that should be a larger proportion of the total points. Or if the main goal is organization, that should be the largest category. I always do my rubrics out of 100 points to make it easy for students to see their grades.

- Use wording that matches the wording in the assignment. For example, if the teacher describes mechanics as “grammar, spelling, and punctuation,” that is how it should be worded on the rubric.

- Use the rubric throughout the writing process. Go over the rubrics with students at the beginning of the writing assignment. As each lesson is completed, remind students of what part of the rubric they are working on. During the revision and proofreading process, have students work through the rubric one category at a time.

Works Cited

“Common Core State Standards Writing Rubric.” 2014. https://www.csun.edu/sites/default/files

/Common%20Core%20Rubrics_Gr11-12_turn_it_in_0.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

Fuglei, Monica. “Rubric’s Cue: What’s the Best Way To Grade Essays?” Resilient Educator, 12

Nov. 2014. https://resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/essay-grading-

rubrics/#:~:text=Because%20a%20rubric%20identifies%20pertinent,criteria%20in%20the%20 writing%20assignment. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

Photo by Afif Ramdhasuma on Unsplash.

Pedagogical Moments: Metaphor

In the land beside the sea, the Great Teacher taught the multitudes. In His teaching he used stories, he asked questions and demonstrated with objects. He was also a Master of metaphor or comparison.

He said, “Men do not light a candle and put it under a cover, but on a candlestick and it sheds light to all the house. Likewise, let your light shine before men that they may glorify your Father in Heaven.”

He warned, “Beware of false prophets who come in sheep’s clothing but really are ravening wolves.”

He exhorted, “Those who hear my teachings and follow them are like a house built on a rock.”

He entreated, “The kingdom of heaven is like a treasure hid in a field. It is like a merchant seeking for good pearls and it is like a net thrown into the sea and filled.”

He stated, “I am the good shepherd. I am the true vine. I am the bread of life. I am the living water. I am the way, the truth, and the life.”

He taught, “A sower went forth to sow. And as he sowed some seed fell by the wayside, some seed in stony places, some among thorns, and some on good ground.”

Metaphor simplifies

A good teacher learns to use metaphor or comparisons to simplify concepts and lessons. Metaphors are comparisons of a new idea with something already understood. Metaphors recall the experiences of the known and place them upon the new concept. Metaphors also help facts and concepts be retrieved from the brain.

Metaphors give us mental pictures that make connections what cannot be readily put into words. I remember a co-teacher once describing her students as a team of spirited horses. When the teacher had control of the reins, good things were accomplished. But the team was always at the point of wanting to take off on their own and the teacher needed a steady hand on the reins. This mental picture expressed much in a less critical manner than a bold statement would have.

Metaphors are especially helpful in teaching young children who do not yet have the language capacity to express themselves fully. If you listen to young children, you will find them creating their own metaphors when they don’t know how to explain what they need.

Examples of metaphor

Metaphors give us hooks to hang things on for easier retrieval. Many memory aids are a type of metaphor. Understanding that the silent “e” a the end of a word gives the main vowel the long sound (all abstract ideas) is more readily remembered with the idea of Mr. E having a long arm that reaches over the neighboring consonant and taps the vowel, reminding it to say, “__”. Young students enjoy the visual image and the metaphor sticks in their brains.

A common kindergarten or first grade penmanship metaphor is comparing the various penmanship lines to a house: basement, floor, ceiling, roof. Placement of the letters is reinforced by the metaphor. Students enjoy stomping through the floor to the basement when they write g, j, p, q, or y. Lower-case f is so tall that he must bend his head because he can’t stick it out the roof.

A classroom management metaphor could be a basketball game. There are rules to follow. The players (students) must know and understand the rules. The coach (teacher) explains and demonstrates how the game is played. The players practice until they can execute the rules. The referee (teacher) calls the infractions as they see them.

Young students walking down the hall as a line of little ducks or as quietly as a mouse is much more fun and interesting than simply walking in a straight line and not talking.

An imaginative teacher will find metaphors in their everyday lessons to help students understand, remember, and learn. Students can also learn to find metaphors to aid their learning.

The Great Teacher taught with authority and not as the leading teachers of His day. He made use of stories and metaphors. He asked probing questions and illustrated his teachings with objects. Those listening to Him recognized the truth He taught and were amazed. Some acknowledged Him and some turned away. The choice was theirs, but this Master Teacher made His truth plain by the way He taught.

Photo by Henri Guérin on Unsplash.

Paradox in the Classroom: What to Do?

Consider the following scenarios:

- A student struggles to remain in his seat throughout the day and, as a result, is falling behind in his work. In order to help him catch up with the class, you consider keeping the child back from recess or another break in order to work on his missing assignments. At the same time, you know that this student would greatly benefit from the chance to release some energy.

- In an effort to stay on track with your curriculum requirements, your class is working on several rigorous projects in the same week. Several days into the work, you begin to notice that your students are looking tired and losing their motivation. You begin to wonder how you might give your students a boost to help them finish their projects well. However, you know that time is limited, and the projects should ideally be finished by Friday afternoon.

- You are teaching a lesson you have taught many times before in years past, and it has always gone well. Today, however, it feels to you as if your words are falling on deaf ears and the concept does not seem to be connecting. In the moment, you consider your lesson plan in light of the remaining time and wonder what you should do. You feel responsible to teach your curriculum well, but at the same time, you know finishing your plan ‘as-is’ would be a waste of time.

If you look closely, you will notice a common theme present in these examples. In each situation, a teacher is finding himself in a position where a decision needs to be made between two equally valid options: completing assignments vs. enjoying a break; rigorous learning vs. boosting classroom joy; sticking with your plan vs. embracing spontaneity. As you think about your own teaching experiences, you can likely think of other examples of paradox—statements or scenarios that are as contradictory as they are complementary.

It is true that students must be held accountable to finish their work, yet many of the students who struggle in this area are also those who would benefit the most from a break. Rigorous activities are the essence of academic excellence, but what would our classrooms be like without an equal dose of joy? It takes a high-level of control on the teacher’s part to execute a lesson plan without veering too far off-topic, but it may require an even higher level of skill to be able to go off-script in a way that would benefit the class.

One of the definitive aspects of a paradox is that the tension persists over time. In other words, the pressure we feel to choose between two seemingly contradictory needs will still be at work in our classrooms tomorrow, next week, and even next school year. In fact, if you take the time to drill down into nearly any ongoing problem you face in your classroom, you may find that it is deeply rooted in one of many common paradoxes: today vs. tomorrow; work vs. home; ends vs. means; and warmth vs. firmness.

For teachers, the question is this: How do we respond to a paradox in a way that benefits our students and enhances their learning? As we think about the paradoxes at work in our classrooms, there are a number of helpful things to keep in mind:

- Consider your situation in light of a balance beam - or any other narrow object that might beckon children to see how far they can walk before falling off. Successfully maneuvering such an obstacle requires frequent shifts of one’s weight to the left and right based on the needs of the moment. At times, one might have only a split second to adjust. Navigating paradoxes in the classroom can be very similar. Give yourself permission to oscillate between the opposing sides of a paradox as the situation requires (Smith & Lewis, 2022). Some of the greatest mistakes we can make in our teaching occur as a result of either knowingly or unknowingly avoiding one side of a paradox.

- Find a win-win through considering a compromise. For example, perhaps you have tried maintaining a strict boundary around bringing work home to complete after school, but the tension between your teacher identity and other responsibilities has left you feeling discouraged as these duties pull you in opposite directions. Instead of feeling disappointed, consider ways that you can accomplish your school tasks and still meet other obligations. Perhaps finding a quiet hour early on Saturday morning with a freshly-brewed cup of coffee to invest in school work will leave you feeling less pressure throughout the week without causing any major disruptions in your typical weekend plans. Satisfying responses to a paradox can often be found by those who are willing to consider an unconventional, outside-of-the-box solution (Smith & Lewis, 2022).

- We are not alone. Many people have passed this way before and have struggled with the same tensions in their teaching. Remember: paradoxes are persistent by nature! Use this to your advantage by learning how others who have gone before you have been able to find a path forward through the contradictory demands of the classroom.

- Consider how Jesus, the Master Teacher, dealt with paradox in His ‘classroom’. He went beyond simple acknowledgement to fully incorporating paradoxical statements into His teaching to give His audience a greater vision of the Kingdom. Consider teachings such as “For whoever desires to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake and the gospel’s will save it” (Mark 8:35, NKJV) or “...but whoever desires to become great among you shall be your servant” (Mark 10:43, NKJV). Furthermore, He did not share these statements as mere enigmatic words or philosophical sentiment; He lived them out as an example for us.

Your classroom paradoxes await you. How will you respond?

References

Smith, W., & Lewis, M. (2022). Both/And Thinking: Embracing Creative Tensions to Solve Your Toughest Problems. Harvard Business Review Press.

How Much Commitment Does It Take to Be a Teacher?

Two former students of mine asked me to fill out a survey for papers they are writing about becoming teachers in the future. The questions were thought-provoking, and I thought the answers might resonate with others and hopefully be encouraging, so here they are.

How much time do you spend on school-related activities each week?

I try not to track it, but it's around 45-50 hours a week.

How does your job affect your mental health and social life?

Teaching is usually a very uplifting and exciting thing to do, and one that I enjoy greatly, so in that aspect, most of the results of teaching on my personal life are highly positive. It does take a lot of time, so I have to work at prioritizing my family—trying to come home fairly early (hopefully after all my papers are graded), and only working on school stuff at home if everyone is out of the house or napping. At times it can be stressful, like when a parent or administrator has "concerns." This would negatively affect my mental health, but these incidents are usually very rare and short-lived.

How much commitment will it take to be a teacher?

To do it well, I would say it takes a lot of commitment. That doesn't necessarily mean a lot of time though, if you've got your ducks in a row. Each year it gets easier as you've often taught the same material before, and you've got more experience in how to handle various situations.

The commitment, I believe, comes in the form of classroom management and knowing the content well. If teachers haven't previously studied fairly extensively in their content area, they are going to have to be committed to putting some time into studying, or they won't be nearly as effective in the classroom. The classroom management aspect is probably the most trying for a teacher. To do that well, one has to be committed to having a classroom management plan and sticking to it.

What are the ministry opportunities? What place does your faith take in the workplace?

Great question! Since I have a degree in my field, I could go down the street to any public school and make about four times the amount of money that I'm making now. But, I believe in Christian education. I am a firm believer in Anabaptist doctrine, and in an Anabaptist school, we get to discuss this every day in Bible class or whenever else it comes up.

I also believe in giving back to the community of which I am a part, and in which my family and I have been so richly blessed.

In addition, I believe that eight-year-olds are not missionaries. I do not believe in sending young children out to be "salt and light" when they don't completely understand doctrine, or a whole lot else for that matter. For this reason, I believe that they need to be nurtured, instructed, and taught in a doctrine-rich setting such as that provided by Anabaptist schools. Then, when they are older and more mature in their faith, they can go out and be missionaries. Someone needs to teach them while they are young. I feel that this is my mission field for now, although I realize that God uses different people’s talents in different ways. This is just where I feel led to be right now.

What are the two biggest life lessons teaching has taught you?

I've learned a lot and am still figuring some things out, but the two most impacting aspects have been the following:

- to be kind to everyone as much as possible, and

- to love my content matter, the process of teaching, and my students.

Will your teaching job be replaced by technology?

NEVER. Having a real teacher in the same room with the students cannot compare to any other option in my opinion. Although it can work (hello, Covid!) long-distance learning is an out-distanced second place to in-person learning in my opinion.

Would you recommend this job?

Absolutely—if it's a good fit for someone. He or she should have a love for learning and a love for students. It is hard work preparing lessons, teaching, managing the classroom, and grading papers. But it's also one of the most rewarding jobs anyone could ever have.

Not only is teaching rewarding, exciting, and fulfilling, but because teaching involves imparting knowledge, encouraging, and working with humans, I believe it is one of the most worthwhile ways a person could invest his time.

When I look back on my past work, I don't have a grand structure I built, a large bank account, or a well-managed store or business. But, I do get to look back on the lives of students whom I have taught and have hopefully had a positive impact upon. That's gold—way more important than buildings, money, or a well-managed, successful business.

What natural abilities or interests are needed for this career?

A teacher needs to have the ability to learn well and study hard. Mastery of content area is muy importante. A teacher should also love learning and humans—and be able to diagram sentences or work complex algebra problems on the board while observing that note being passed or those two girls talking in the back.

What is the wage for this job?

The average teacher salary in the state of Pennsylvania is $67,000. I've made anywhere from $12,000 to $37,000 a year, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Communications, plus two additional years spent in college becoming certified to teach secondary English. That's pretty pathetic pay for Christian schools. But I still believe in what I'm doing, even if I'm not making a lot of money. (See answer to the ministry opportunity question.)

I do desperately wish that things were different, and that teachers were valued monetarily as much as mini barn builders and construction workers. We are certainly responsible for more important material (little humans!).

I will add that this is the biggest downside to the job, as well as the most important reason that gifted teachers, especially qualified men, are not more interested in spending their time in the classroom. That is a shame.

Are there a lot of job opportunities for teachers?

Absolutely. Because it's hard work and involves juggling content area, students, parents, administration, paperwork, and more, there are not a lot of qualified teachers, nor enough of us willing to take on such an important task. It's also difficult because one has to prepare lessons beforehand, teach all day, and then grade papers after school. Most people just do their work and go home. Teachers have way more to do. But the rewards we reap are greater and have eternal value. That makes it worth it from my perspective anyway.

Blessings as you prepare and study to become a teacher.

Mrs. Swanson

Teachers are Mentors

I would invite you as we think about "Teachers are Mentors" to turn in your songbooks to number 585. We have a very common song. The words of this song, I think, are very meaningful in this talk. It's the song "Follow the Path of Jesus." And if you think about it, this is what Jesus did with his twelve disciples. He simply invited them to walk with him for three years, and then he said, "Now go and preach. Baptize and teach in all places." That is what we are called to do as teachers is to impact lives as Jesus did.

What is a mentor? I think mentoring is taking your life experience and giving it away for free. What cost you blood, sweat, and tears, agony, sleepless nights, and lots of years of experience, and you just offer that to a younger person for free.

Sometimes you see positive outcomes for your investment and sacrifice, and sometimes you don't. I think mentoring in a Christian school setting is more like this. It's a miracle in which a special relation, a relational bond, is formed between two people, one with more experience than the other. Because of this special bond comprised of deep trust, admiration and relationship, God molds and changes their lives forever. I would suggest that he changes and molds both of their lives in a better way.

Sometimes this relationship is intentional, and sometimes it isn't intentional. It just happens. Here's the scary part. Sometimes the mentor isn't even aware of the relationship. Now don't let that paralyze you this morning. I would say to you, cling to the hand of Jesus. Follow him day and night, and you'll do alright.

I suggest to you that there are three A's of mentoring, if this is helpful. It's gonna take active listening, and you listen and listen and listen. And I think you are earning the right, then to say a few sentences at the end.

It means availability. Availability is a big thing, and it's not gonna suit your schedule. It's it's not gonna happen when it really works well for you.

You're going to need to analyze their issue. I often send a quiet prayer up to God and say, "I have no idea what to say. Give me words. Give me words for this person because they they're seeking direction. They wanna know what I think. I wanna know what you think." And you're going to need to be kind, and you're going to need to be truthful.

Think about mentors and what mentors do. Mentors give second chances. Mentors allow for mistakes. Good mentors actually expect mistakes. I like to see mentors who are so close to the situation that when the young man drops the ball, they actually catch it before it hits the floor. They don't let the thing go splat. But you can't always do that. But good mentors are going to realize that they're gonna be let down.

I would suggest that mentors take risks on inexperience. They, in fact, risk their own reputation sometimes. They risk mature relationships for the sake of the inexperienced and that relationship.

It doesn't always go smoothly. Mentees. I'm not really familiar or comfortable with that term, but the person being mentored sometimes fails. And even more sadly, the mentor fails sometimes. I have failed as a mentor. I have let people down that were depending on me. Both ways. So many times I forget how many chances it took for me, how many risks others took on me, how many chances they took.

You know, sometimes you teach and you interact, and these people move out of your lives. And and here is a little push encouragement for that experienced teacher that you had a relationship with this person, but now they're grown up and maybe they have a big truck and, you know, a gun rack in the back and stuff like that, and they seem really tough. Don't hesitate to seek them out and talk to them, because you still mean more to them than you will ever know. And you still, with a few words, can light their path and direct their way. Even if they're going a wrong way, reach out to them.

Baidon was about thirteen or fourteen when he came to grade five at our school. And since our school only went to grade six, he was there for two years, and I would see him at school. And he started coming to our church, and he was there for Sunday school. And often on Sundays, he would just stay at our house for lunch, and he'd be there in the afternoon and sometimes go to church with us in the evening, and that that was pretty much the extent of our relationship. He became a Christian at our church and joined instruction class. And as the pastor, I took him through instruction class.

And then one day he came to instruction class, and he was really troubled. And he wanted to talk to me. And he said, "I have a problem. You see, my mom became a Christian."

She was a single mom, and she was raising her two youngest boys, Baidon and his younger brother. Their dad who walked out on their family years before, and his mom had become a Christian at one of the other evangelical churches in town.

And he said, "My problem is that my mom wants me to go to church with her. I don't know if I did the right thing."

I said, "Baidon, you go to church with your mom. They use the Bible over there too. If you want to learn from God, you can learn from God there. You don't have to come to my church."

And so he did. He went to church with his mom, and our school didn't go any further. He went to another school for a while and then dropped out. I heard he was driving truck, and I I saw him once in a while in our town.

And years went by. And then one night, I got a call late at night from an unregistered number. But I took it, and I heard, "Stephan. Is that you, Stephan?"

I said, "Yeah. Who's this?"

He said, "I'm Baidon.

Like, "Okay, Baidon? Are you alright?"

He's like, "No. I'm not okay. I just backed over a little girl and killed her."

And I said, "Baidon, where are you?"

And he told me. I said, "I'll be right there."

"You need to understand that in Guatemala, if you kill someone with your vehicle, you're about as guilty of their death as if you take a gun and shoot them. So Baidon was in big trouble.

And I was there with him when the police came and when the lawyer came. And sitting there, I thought, you know, I had no idea how much our relationship meant to him. But I was the one he called when he was in trouble. And I would encourage you when you get that call, be there for them. They need you. I think there are a lot of flowers out there waiting for the end of August or the beginning of September to blossom under your caring, sympathetic influence.